Did the ALS 'Ice Bucket Challenge' really help research? Scientists say yes

Loading...

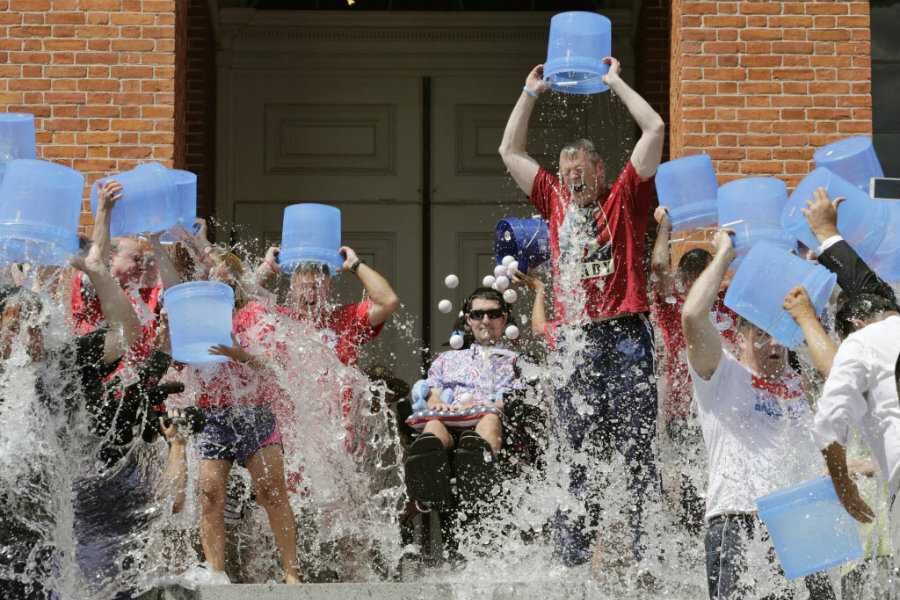

For a few weeks last summer, the “Ice Bucket Challenge” was a full-on viral phenomenon, driving celebrities and everyday folks to post videos of themselves getting doused in ice water and raising millions of dollars to spread awareness of ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease.

Now the campaign appears to be paying off, highlighting the idea that social media advocacy – which has been criticized as low-investment activism, or “slacktivism,” if not outright ineffective – may, in some cases, provide a path to real results.

A new study published last week in the journal Science that sheds new light on the illness was one of many funded by the $200 million raised through the Ice Bucket Challenge, the Washington Post reported. The team behind the research, led by Johns Hopkins professor Philip Wong, had been studying ALS for a decade, but the funds the challenge brought to the field propelled them to pursue riskier, and potentially more rewarding, experiments.

"The money came at a critical time when we needed it,” Dr. Wong told the Post. "Without it, we wouldn't have been able to come out with the studies as quickly as we did.”

As Internet use rises in the US – the Pew Research Center reports that more than 85 percent of American adults now use the Internet and 24 percent of teens are online “almost constantly” – the use of social media as a tool for advocacy, awareness, and activism has grown, as well.

"One of the great things about social media is it creates more of a conversation ... as opposed to the [strategy of] one-way, 'Watch our PSAs' or 'Read our mailers,' " Jonathan Obar, an assistant professor of communications studies at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology, told USA Today. "It's a conversation that can lead to more engagement."

Indeed, that ability to reach out and connect with audiences on a personal level has spawned a multitude of online campaigns-for-a-cause that range from #BringBackOurGirls to #JeSuisCharlie to #ICantBreathe.

The problem, however, is that while many of these campaigns develop a kind of brand recognition, they rarely push people to action.

Critics of “Bring Back Our Girls,” for instance – which began in April 2014 as a call to release more than 200 young girls kidnapped from a Nigerian village by the extremist group Boko Haram – said the “hashtag represents the positive aspect of spreading awareness, but unfortunately fails to achieve peace or action in the area,” The Christian Science Monitor reported a year after the campaign took off. “Women are still being abducted by Boko Haram.”

The Ice Bucket Challenge, though it saw tangible results for the ALS Association in the form of hard cash, received similar criticism. Slate’s Will Oremus noted that the charity portion of the challenge remained an afterthought, something to be done as an alternative to being drenched in icy water.

As for “raising awareness,” few of the videos I’ve seen contain any substantive information about the disease, why the money is needed, or how it will be used. More than anything else, the ice bucket videos feel like an exercise in raising awareness of one’s own zaniness, altruism, and/or attractiveness in a wet T-shirt.

Still, researchers who have received funding from the challenge have said that the effort was meaningful. In an “Ask Me Anything” thread on Reddit, Jonathan Ling, another scientist at Johns Hopkins, tried to address comments that the endeavor was a waste.

With the amount of money that the ice bucket challenge raised, I feel that there’s a lot of hope and optimism now for real, meaningful therapies. After all, the best medicines come from a full understanding of a disease and without the financial stability to do high risk, high reward research, none of this would be possible!

One campaign that did see success – both in awareness and action – is #GivingTuesday, founded by social marketing whiz Henry Timms in partnership with the United Nations Foundation. The movement encourages individuals, companies, and communities to give back on Dec. 1, and since it started in 2012, has engaged more than 30,000 organizations worldwide.

Mr. Timms’s advice to other groups who want to use social media for advocacy is to develop a strategy that encourages people to make the cause their own.

“The challenge ahead, for any organization trying to create movements at scale, is not simply to master social media, but to learn to shape and support social communities,” he wrote for the Harvard Business Review. “This will require not just new toolkits, but new mindsets.”