Be like Fauci? Pandemic inspires surge in med school applications.

Loading...

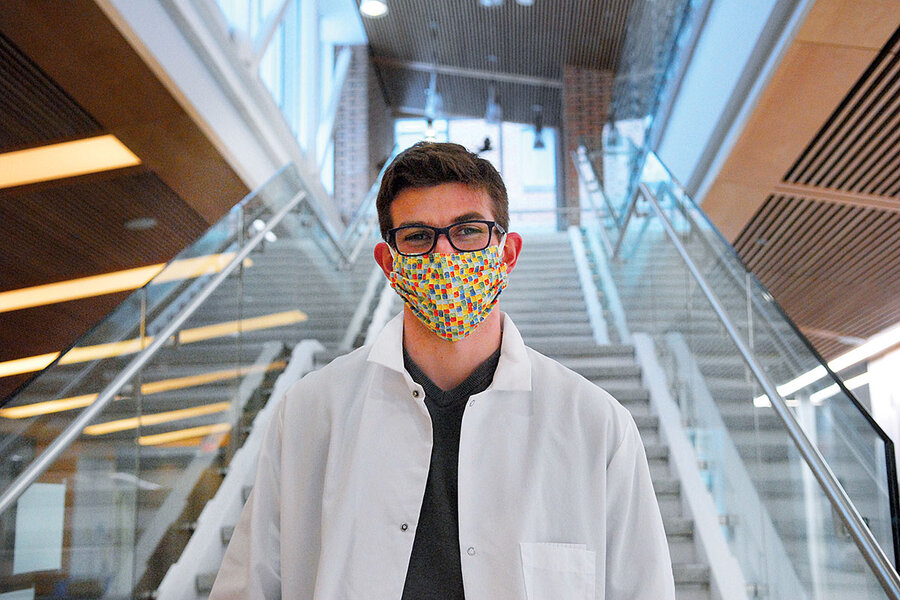

When Ryan Farmer dressed up as Dr. Anthony Fauci last Halloween, he was trying on more than a costume. He was embracing a calling.

He’s not sure what kind of doctor he wants to become. But inspired by the selflessness and community service of medical workers over the past year, Mr. Farmer is now preparing his application for medical school.

Why We Wrote This

What makes people devote their entire lives to serving others? Witnessing the selflessness of medical personnel during the pandemic has helped to inspire thousands of prospective medical students.

“All of those people who’ve been sacrificing so many things in their lives to help all of us,” he says. “Those are the people I want to be.”

Across the country, medical school applications are soaring, up 18% this past year, an enormous jump for the field.

Perhaps not since 9/11 – when droves of young people followed the career footsteps of first responders, soldiers, and firefighters – have current events shaped the area of work people pursue, says Mary McSweeney, assistant dean for admissions at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s School of Medicine and Public Health.

“People who go into medicine want to help people,” says Dr. McSweeney, “and this is the ultimate time to help people.”

Wearing khakis, glasses, a tie, a lab coat, and some dry shampoo for a touch of gray hair, Ryan Farmer added the pièce de résistance to his Halloween costume last year – a simple name tag reading “Dr. Fauci.”

With that, Mr. Farmer had become the nation’s top expert on infectious disease. In a year defined by the coronavirus pandemic, there hardly could’ve been a more appropriate outfit. To Mr. Farmer, it was more than a costume. It was a calling.

A senior at William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, Mr. Farmer is now preparing his application for medical school. He may not be tomorrow’s Anthony Fauci. He’s not even sure what kind of doctor he wants to become. But inspired by the selflessness and community service of medical workers over the past year, Mr. Farmer hopes to eventually wear his lab coat at work each day and not just on Halloween.

Why We Wrote This

What makes people devote their entire lives to serving others? Witnessing the selflessness of medical personnel during the pandemic has helped to inspire thousands of prospective medical students.

“I think the kind of people who have stepped up all around the country are the kind of people we need more of,” he says. “I want to be a part of that community.”

Across the country, many young people planning their careers share the same sentiment, and are taking steps to make it a reality. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), medical school applications for this year rose 18%, an enormous jump for the field. While these applicants won’t practice during the COVID-19 pandemic, their increase is tangible evidence of a rally-round-the-flag effect in public health and medicine, which could help stave off a looming shortage of medical workers in the next decade.

Perhaps not since 9/11 – when droves of young people followed the career footsteps of first responders, soldiers, and firefighters – have current events shaped the area of work people pursue, says Mary McSweeney, assistant dean for admissions at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s School of Medicine and Public Health.

“People who go into medicine want to help people,” says Dr. McSweeney, “and this is the ultimate time to help people.”

Over the past 20 years, medical school applications have risen only slightly, just 2.5%, despite a 16% growth in population. That makes this past year’s near 20% jump an almost unprecedented aberration, says Geoffrey Young, the senior director of student affairs and programs at the AAMC.

A number of factors are likely driving that surge, he says.

For some it may come down to simple logistics.

To be competitive, medical school applicants must start building a portfolio in their first year of college. Yet the gap between a portfolio and an application can be wide. A rise in free time during the pandemic, says Dr. Young, may be giving young people more time to apply.

But the pandemic has also given public health officials broader visibility among the public. The so-called Fauci Effect, named after Dr. Fauci, may inspire increased interest in medicine and public health for years to come as students enter college during the pandemic, says Dr. Young.

Such attention could bring a welcome boost in funding for medical schools and internship programs, perhaps helping remedy an impending physician shortage projected by the AAMC.

“This has been a really great opportunity to be able to teach public health, because when you have a pandemic going on, obviously it’s captured the entire nation’s interest and it gives a real context,” says Dr. McSweeney.

A spotlight on public health

For those already studying medicine and public health, the pandemic has added resonance to their education.

Samantha Banks applied for the University of Washington’s master’s in epidemiology program because she wanted a career that met people’s needs in real time. Then the pandemic hit, and suddenly a formative moment in Ms. Banks’ education coincided with a formative moment in the field at large.

“COVID might have put the spotlight on public health a little bit more than anything else,” she says, now in her second semester in the program and still deciding where she wants to work after graduating – a choice the pandemic is certain to affect.

In contrast, across the country in Norfolk, Virginia, Ashley Carter has known what she wants to be since she was 10 years old. “COVID or no COVID, I was going to do the same thing I’m doing now,” says Ms. Carter, in her first year studying to be a neurosurgeon at Eastern Virginia Medical School.

Still, the pandemic has validated her idea of what doctors do: prepare for and respond to emergencies.

Amid such a turbulent year, with the pandemic forcing her first two semesters of medical school online, the example set by medical workers reminds her of what she aspires to be. Some may look to Dr. Fauci, she says, but there are millions of other medical workers in the United States who don’t have a camera on them.

“Every nurse, every doctor, every sanitation worker, every single person who is a part of the health care system, to make it run and sustain the system in general throughout this time, is a hero to me,” says Ms. Carter.

Someone to look up to

Jenny Shen, a researcher at Columbia University Medical Center, is one of those near-anonymous employees.

In 2015, Ms. Shen left her job in banking and enrolled in a biostatistics program at Columbia, where she’s worked since graduating.

It was difficult at first, she says, adjusting to the patience required in the field. Her research didn’t have a clear destination, and at times she wondered if she made the right choice.

But since the pandemic Ms. Shen has seen the ability of her field to meet the needs of the moment. Though her existing research has continued, she’s also contributed to COVID-19 research and data collection in a partnership with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

For her, the last year has been a live lesson on the importance of medicine and public health – especially the example set by her co-workers.

“During April, May, that darkest time in New York City, I saw my colleagues were so brave to go to the hospital,” she says. “They really, really inspired me.”

Even though he’s years younger than Ms. Shen and only has a vague idea of his future, Mr. Farmer, the senior at William & Mary, finds inspiration in the same place.

“All of those people who’ve been sacrificing so many things in their lives to help all of us,” he says. “Those are the people I want to be.”