Sexism isn’t a relic of the past. How men’s views are shifting.

Loading...

The share of Americans who think men are better suited than women for politics has decreased from 44% to just 13% in the past five decades, according to the General Social Survey at the University of Chicago. Today, only 4% of Americans say they won’t support a woman for president. With these changes as a backdrop, a woman won the popular vote for president four years ago. But the ranks of women in elective office have grown slowly, and the U.S. Congress is still more than three-fourths male.

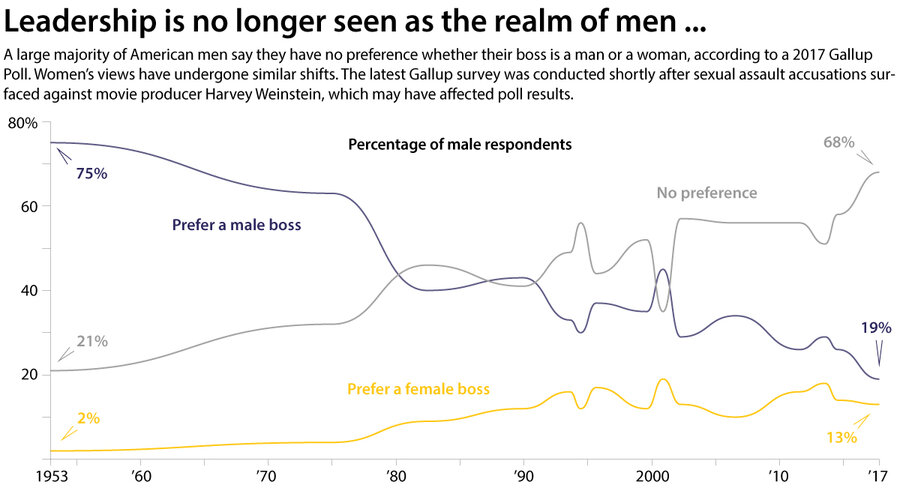

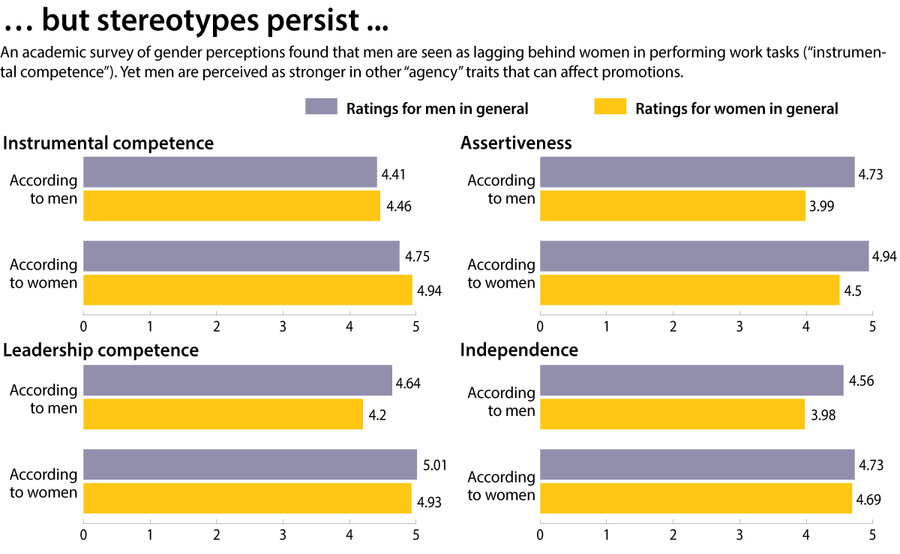

In workplaces, perceptions of women’s competence have soared since polling began in the mid-20th century, says Alice Eagly, a professor of psychology at Northwestern University and a leading expert on gender norms. Yet stereotypes persist. Men are perceived as stronger in “agency” traits like assertiveness, while women are seen as more communal, she says. Just 7% of Fortune 500 corporations are led by a female CEO.

“That’s the myth in some ways, when we look at things and say 100 years ago it was so much worse ... that things are always getting better,” says Leisa Meyer, a historian at the College of William and Mary.

Why We Wrote This

For U.S. women, having the right to vote hasn’t automatically translated to power. Changed perceptions of women’s capacities are another key step. Part of our special 100th anniversary edition on women winning the right to vote.

Cory Weller, a recent college graduate and resident of Columbia, Maryland, says he supports gender equality. He’s voted for a woman. He reports to a female manager at work. In college, he took a course on feminism.

His thoughts on gender don’t run in the family. Mr. Weller says his father would balk at a female leader or boss. It’s a difference that, in his opinion, comes from circumstances as much as stereotypes. More than half of his bosses have been women, he says, and none of his father’s have been.

“There are no real differences in males or females that should set them apart from having equal roles,” says Mr. Weller, “which I feel like is kind of a new viewpoint.”

Why We Wrote This

For U.S. women, having the right to vote hasn’t automatically translated to power. Changed perceptions of women’s capacities are another key step. Part of our special 100th anniversary edition on women winning the right to vote.

In part, the younger and older Wellers represent America’s shifting attitudes toward gender, which have been especially malleable since the ratification of the 19th Amendment a century ago.

Yet, even as attitudes keep evolving for young and old alike, the reality on the ground has a lot of catching up to do. Leadership roles in both business and politics are still occupied heavily by men.

One moral of the story, say legal scholars and historians, is that new perspectives alone don’t eradicate biased behavior. It requires focused effort to dismantle systems and traditions that inhibit women’s advancement. Perception shifts are just one step – but an important one.

“At what point does culture change?” asks Swanee Hunt, a former U.S. ambassador to Austria and a scholar at Harvard University. “The answer is it’s changing every nanosecond. It is never not changing, because all culture is, is the way things are being done.”

The shifts over the past century are both significant and incomplete. The share of Americans who think men are better suited than women for politics has decreased from 44% to just 13% in the past five decades, according to the General Social Survey at the University of Chicago. Today, only 4% of Americans say they won’t support a woman for president. With these changes as a backdrop, four years ago a woman won the popular vote for president. But the ranks of women in elective office have grown slowly, and the U.S. Congress is still more than three-fourths male.

In workplaces, perceptions of women’s competence have soared since polling began in the mid-20th century, says Alice Eagly, a professor of psychology at Northwestern University and a leading expert on gender norms. Yet stereotypes persist. Men are perceived as stronger in “agency” traits like assertiveness, while women are seen as more communal, she says. Just 7% of Fortune 500 corporations are led by a female CEO.

“That’s the myth in some ways, when we look at things and say 100 years ago it was so much worse ... that things are always getting better,” says Leisa Meyer, a historian at the College of William and Mary.

Compared with a century ago, Dr. Meyer sees progress, but she says far more is needed. Women aren’t only judged differently for the same behaviors, she says; they’re also still thought of as more emotional, worse leaders, and less apt to make hard decisions. Those perceptions tend to be held most strongly by men.

Yet many women hold similar gender stereotypes as well. And that’s an important twist, when it comes to battles for equality. This year, after all, protests for racial justice have encouraged a reckoning over racism in America. In many ways, the quest for gender equality is a parallel battle, but experts say women are less cohesive as a group than African Americans when it comes to a sense of shared struggle against long-standing injustice.

That’s not to say society never confronts sexism. The #MeToo movement unleashed a powerful shift in public thought regarding sexual harassment. Calls for equal pay have also galvanized growing support from men as well as women in recent years.

But achieving lasting change is hard work. Cultural shifts, Dr. Meyer says, involve each generation doing things differently and passing those differences on to the next. And that process is rarely linear.

Bradley Jean is one young man who thinks stereotypes are losing their sway. A rising senior studying computer engineering at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia, he’s excited to already have a plan for work after graduation. The CEO at Novetta, the software company where he has been promised a job, is a woman – Tiffanny Gates. She is a strong leader, he says, and she’s created a culture of open, supportive communication – something Mr. Jean appreciates.

“If [women] have the same qualifications as men,” he says, “they should be judged on the same principles.”

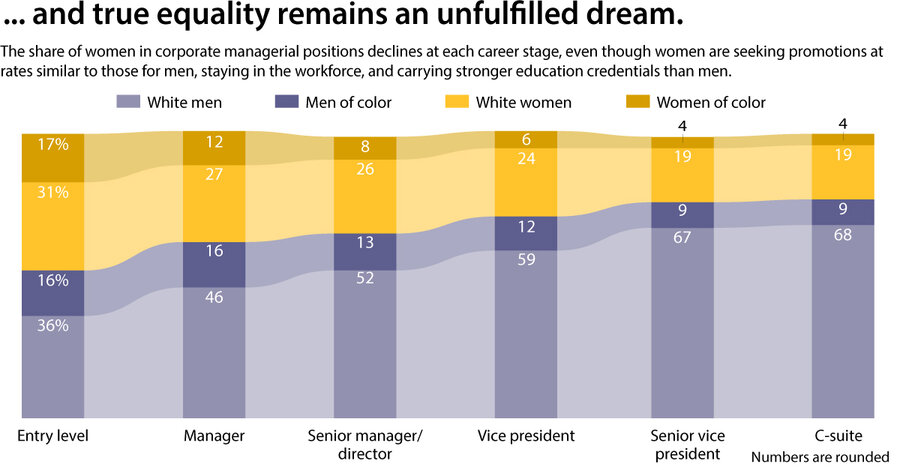

Yet that still rarely happens, says Joanna Grossman, a legal scholar at Southern Methodist University. She describes the workforce as a pyramid shape for women, in which they’re equally represented at the bottom “and they drop off at every meaningful level.” Men in particular need to accept that sexism isn’t just a relic of the past, she says.

Dr. Hunt at Harvard believes that her students should play an active role in ensuring the success of their classmates – women and men. She tells them, “It’s not about ‘Just get out of [women’s] way.’ It’s walk the journey with them.”