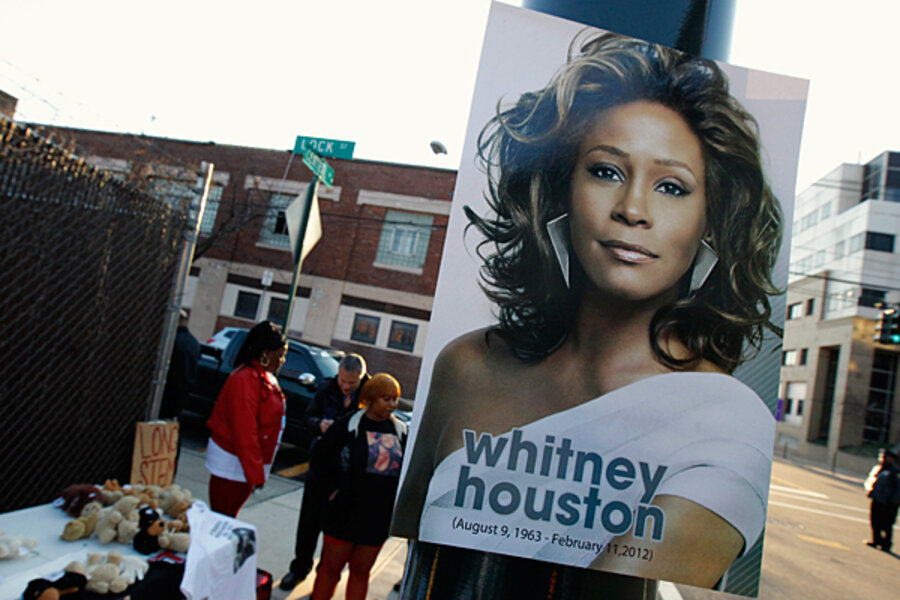

National Enquirer ignites furor with Whitney Houston casket photo

Loading...

| Los Angeles

The National Enquirer’s decision to feature cover photos of the late Whitney Houston, in a casket, has touched off a furor, raising anew a debate over professional ethics, taste, morality, greed, and privacy.

How and if media outlets should portray people who have died, or who are about to die, is a discussion that has ensued time and again in recent years, with the demise of international figures such as Osama bin Laden, Saddam Hussein, and Muammar Qaddafi; as people leapt to their deaths from the burning World Trade Center towers; and as the remains of US soldiers are returned to America at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware.

The questions include how to resolve potential conflicts among constitutional guarantees, such as freedom of the press and the public’s right to know versus an individual's right to privacy. They are hotly debated in newsrooms and around kitchen tables nationwide, and the answers vary widely within the hierarchy of publications, from strait-laced to tabloid.

Some media watchers seem resigned to media intrusion into individual and collective death.

"Turning dead bodies into cultural commodities violates the basic norm that death is private," says Ben Agger, director of the Center for Theory at the University of Texas (Arlington) Sociology Department, in an e-mail. “But, since the Kennedy assassination in 1963, much death has been public. His brother Bobby died on television, as did many in Vietnam and everywhere one finds inhumanity and war.”

Others see no excuse for publishing photos like the ones on National Enquirer's cover. Fordham University Communication Professor Paul Levinson, author of “New New Media,” sees the issue much more cut and dried.

"Although some people find photos of the dead of interest, the media serve no worthwhile purpose in satisfying that interest," says Paul Levinson, a communication professor at Fordham University," in an e-mail. "The dead deserve respect, and their families are entitled to privacy. The only photos of the dead that should ever be made public are those that may be released by family."

Who snapped the controversial Whitney Houston photos remains a mystery to the public. The National Enquirer did not include a photographer's credit. Two photos are on the cover: one a close-up of Houston's head and torso, and the other from a distance with the casket flanked by two lamps and flowers. The headline reads “Whitney: The Last Photo," and it carries the subdeck “Inside Her Private Viewing." Three bullet points offer the details that the famous singer, who died suddenly on Feb. 11, was “buried in jewelry worth $500,000,” “wore her favorite purple dress,” and “had gold slippers on her feet.” Her funeral, which was private, was held Feb. 18.

Several media outlets have already weighed in with criticism.

The Washington Post said “a line had been crossed.” The website Jezebel called it morbid, and a Los Angeles Times headline read, “National Enquirer Whitney Houston casket photo: Finally too far?”

Beyond the serious issues of taste and morality, the case presents a “teachable moment” for Brett Wilmot, associate director of The Ethics Program at Villanova University in Pennsylvania. A concern for ethics teachers that can be of help to the general public, he says, "is to be aware of how the media is trying to pique our curiosity in ways we might not wish to admit as part of our humanity. It’s a time for each of us to ask what it is inside us that wants to take a peek at photos like this, to rubberneck when passing a roadside crash. It’s a conversation worth having.”

To Russell Frank, who teaches journalism ethics at Pennsylvania State University, the episode is a gold mine for instruction among editors.

“What really leaps out to me is looking at the number of so-called serious publications who are questioning the National Enquirer’s decision, while at the same time capitalizing themselves on the very luridness of the details that they are openly deploring,” he says. “What these folks are doing is not letting this stuff in through the front door, but letting it in the back door just the same.”

If they aren’t providing a link to the picture, they are providing a vivid description of it, he says.

That said, Mr. Frank says a key question editors must ask themselves when deciding whether to publish a photo of an individual's remains is this: Does it advance the reader’s knowledge of anything important about the deceased? An editor might be motivated to show pictures of dead bodies from Syria or Haiti so that readers understand the devastation, and will be moved to send aid or to work to get their governments to do so.

“Pleasantness of the photo is not the issue,” he says. “The photo may make you sick or uncomfortable, but there might be some compelling reason to run it."

The question to ask is “whether the story or picture gives us some insight into the person that can contribute to the audience (which is all of us) learning something about the human condition," says Richard Goedkoop, professor of communication at LaSalle University, in an e-mail. "Unfortunately, in our celebrity/tabloid culture … it is whether this story will attract attention that will improve circulation and sales."

The public itself, he adds, bears responsibility for the National Enquirer episode.

“Those who bought or read the National Enquirer this week are also a major part of the problem, because without them, there would not be an incentive for the photo of Whitney Houston in the funeral parlor to be taken or purchased.”