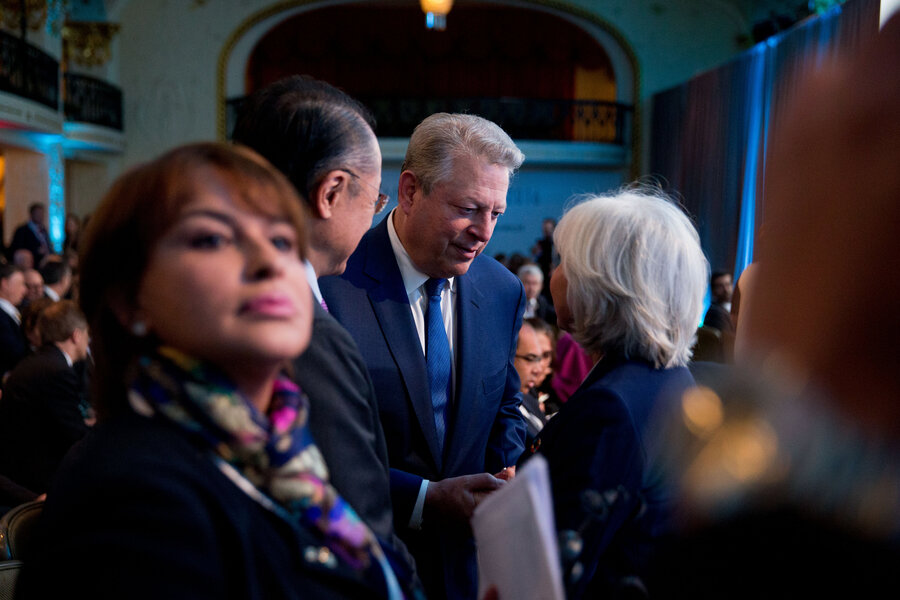

We got Al Gore and climate skeptics in a room. Here's what happened.

Loading...

As we Americans witness one candidate for the presidency of the United States calling climate change a "hoax" while the other considers it is the "greatest threat" to humankind, it is natural to wonder why. Most hard-core environmentalists will simply assume Hillary Clinton is right, while the die-hard conservative climate deniers will simply assume she has her head in the sand.

But the truth is more complex, and also far more hopeful.

More than a decade ago, I witnessed an earlier version of these conflicting views. But unlike the drive-by debates we are witnessing today, the dialogue I witnessed took place went much deeper. What happened during that showdown provides some unique and revealing clues to where we can find common ground.

Imagine for a moment this unlikely scenario.

Al Gore and his colleagues, who were about to release their movie An Inconvenient Truth, spent three days at a retreat center high in the Rocky Mountains with a team from the Competitive Enterprise Institute who had published attack ads dismissing the movie as a liberal lie.

Thanks to some remarkable allies from across the political spectrum, we were able to actually assemble a cross-section of stakeholders from across the spectrum of opinion on climate change. If one wants to understand what is truly going on behind the polarized political positions on this critical issue, the story of what unfolded between Mr. Gore and his critics offers some hopeful glimpses into a sustainable future.

On the opening day, Gore presented his Inconvenient Truth slide show (later to become an Academy Award–winning movie) to the assembled group of 30 "experts," who represented a wide range of positions on climate change. A team of critics from the libertarian think tank then presented their views. They explained why they questioned the validity of the idea of climate change and felt that the green approach threatened jobs, economic growth, and individual liberty.

In addition, there were representatives of faith-based organizations, renewable-energy advocates, and corporate energy industry lobbyists.

My co-facilitator, William Ury, and I led the group through a sequence of conversations that yielded significant learning on both sides. On the final day, Gore acknowledged that he had learned from his critics how he could express his climate change views more effectively to a conservative, business audience. Meanwhile, his critics admitted that underlying their opposition to climate change was, in fact, a deeper concern: they felt the issue was being used as a "cover" for a liberal expansion of government and further regulations in the private sector.

On the final morning, one of the key lessons that Gore told the group that he learned at the retreat was that his approach to climate change appeared to his conservative critics as just another Trojan horse for more government. Like a classic liberal, he had left his critics with the impression that government would be primarily responsible for solving the challenge of climate change.

The CEI conservatives, of course, felt that if any sector would ultimately meet the challenge, it should be the private sector. While they never fully endorsed the concept of climate change, once they felt their concerns had been acknowledged they become intrigued by how the private sector could actually be empowered by being part of the response to the climate challenge.

The key lesson for me was the importance of listening, humility and, above all, learning.

Here was Al Gore, who had spent his life in the political realm from childhood on, and who was perhaps the most widely known climate-change activist in America, who was spending three days learning about the subject. During that retreat, he discovered how to communicate more effectively across the vast political divides. It was a moving reminder that, in a democracy experiencing breakneck technological change, every one of us is still a student.

After all, how can we not be humble? More than 10 years have passed since this meeting, yet the polarized "greatest threat"-vs.-"hoax" conversation continues. Clearly we have to find fresh, bold ways to magnify the private breakthroughs that occurred during our retreat so that they evolve into cross-spectrum collaboration.

Just as a natural disaster, such as a hurricane or flood or forest fire, can unite neighbors across their differences, perhaps the challenge of climate change can one day bring liberals and conservatives together. But for that to happen, we all have to be willing to become learners again.

(Editor's note: The first paragraph of this story was corrected to clarify who climate-change deniers think has their head in the sand.)