The two candidates have sharply divergent views about how jobs are created.

President Obama has tried to get the economy going through federal spending on unemployment benefits, the building of public amenities such as bridges and highways, and money going directly to the states to help pay for teachers and police. Much of this effort was embodied in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act in 2009, which was a $831 billion effort – much maligned by the Republicans – to jump-start the economy during a recession.

Mr. Obama proposed last September a smaller effort of $447 billion that would have provided federal funds to keep 288,000 teachers on the job as well as funding to rehab old schools with new science labs and Internet access. That effort was shot down by the Senate, which could not agree on how to pay for it.

The emphasis on teachers is part of the Democrats’ philosophy of how to create jobs.

Delaware Gov. Jack Markell, who is working with the Obama campaign as a surrogate for the president, says that when he talks to businesses on what they need to grow, one of the first things they tell him is the importance of schools and education. “There is not a chance for the economy without great schools,” he says.

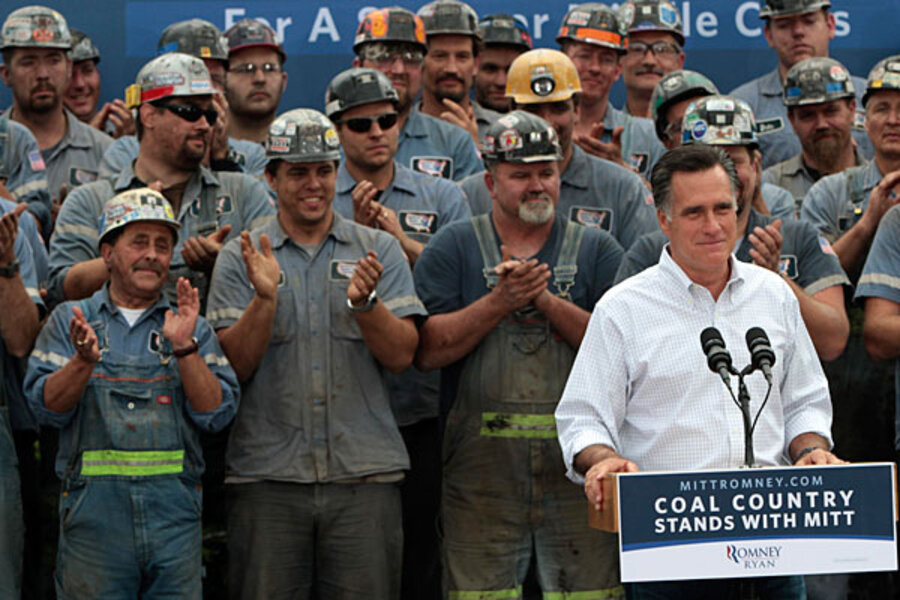

Romney believes in a much smaller direct involvement by government.

“Washington has become an impediment to economic growth,” he wrote in 2011 in his introductory letter to “Believe in America,” his 160-page document on what he thinks needs to be done.

To Romney, the government needs to be pared back. For example, he says there has been a “vast expansion of costly and cumbersome regulation” of energy, finance, and health care. “When the price of doing business in America rises, it does not come as a surprise that entrepreneurs and enterprises cut back, let employees go, and delay hiring.”

As an example of how government regulation has hurt employment, Romney cites delays in leasing new acreage for oil drilling and Obama’s denial of a permit to build a controversial oil pipeline, the Keystone XL, which would move oil from Canada to the Gulf Coast. He says his plan to expand drilling and build the pipeline would create 1.2 million jobs.

At the same time, Romney wants to make corporations more competitive so they hire more people. How? Cut the corporate tax rate from a maximum of 35 percent to a maximum of 25 percent. “Our high corporate tax rate handicaps the overall US economy in our competition with the rest of the world,” he says.