Taking on Trump: How 2024 might be different from 2016

Loading...

| Washington

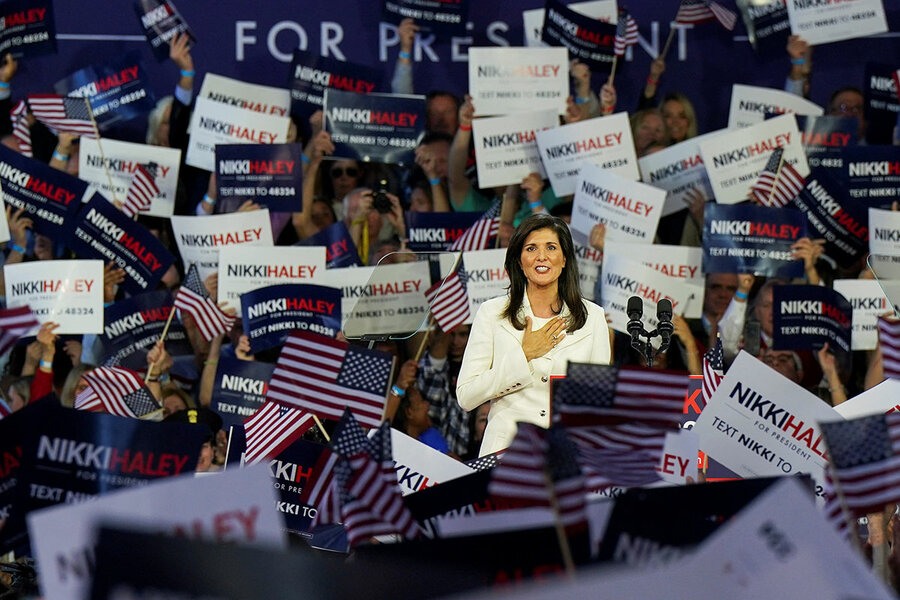

Nikki Haley, former governor of South Carolina, is now officially running for president – the first major Republican to take on former President Donald Trump, a declared candidate since November. Many other prominent Republicans are likely to follow, including Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, by far the strongest competitor against Mr. Trump in polls of GOP voters. Governor DeSantis is expected to announce in several months.

In a basic way, the math points to another 2016. A dozen or more prominent Republicans are expected to get in. President Joe Biden, an octogenarian struggling in the polls, presents a juicy target in his own anticipated run for reelection. And Mr. Trump commands a loyal following of GOP voters – not a majority, but enough to divide and conquer the rest of the field.

Why We Wrote This

A crowded GOP presidential field could help Donald Trump win the nomination again. But many factors are different – including Mr. Trump’s unique status as a “pseudo-incumbent.”

Still, political analysts say, the 2024 cycle is likely to be different in many ways. Mr. Trump is the first defeated one-term president to run for his old office in modern history – and as such, there’s no road map.

“They’re going to have this really crowded field, and tons of candidates that can’t really differentiate themselves from one another,” says Jennifer Lawless, a political scientist at the University of Virginia.

The battle has been joined.

Nikki Haley, former governor of South Carolina, is now officially running for president – the first major Republican to take on former President Donald Trump, a declared candidate since November.

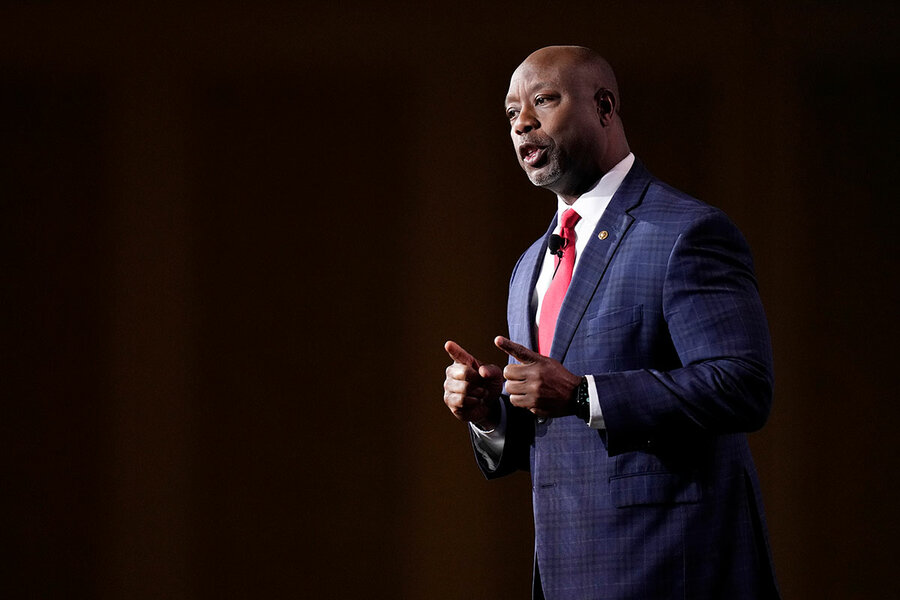

Tim Scott, a fellow South Carolinian and the only Black Republican in the U.S. Senate, launches a listening tour today for his own potential run. Mike Pence, the former vice president, is on a two-state swing ahead of his own possible campaign.

Why We Wrote This

A crowded GOP presidential field could help Donald Trump win the nomination again. But many factors are different – including Mr. Trump’s unique status as a “pseudo-incumbent.”

Many other prominent Republicans are likely to follow, including Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, by far the strongest competitor against Mr. Trump in polls of GOP voters. Governor DeSantis is expected to announce in several months.

All of which raises the billion-dollar question: Will the 2024 presidential cycle be a rerun of 2016, when Mr. Trump clawed his way to the Republican nomination by capturing pluralities of votes in winner-take-all primaries? Or will a new dynamic take hold?

In a basic way, the math points to another 2016: A dozen or more prominent Republicans are expected to get in. President Joe Biden, an octogenarian struggling in the polls, presents a juicy target in his own anticipated run for reelection. And Mr. Trump commands a loyal following of GOP voters – not a majority, but enough to divide and conquer the rest of the field.

“If not the presumptive nominee, he’s certainly the front-runner,” says Republican strategist Doug Heye. “Sure, his numbers have been dipping and we’ve seen instances where his message doesn’t resonate quite as much. But he’s still more than first among equals. He’s got a base; he gets more media coverage than anyone else; he has money in the bank.”

Still, political analysts say, the dynamic of the 2024 cycle is in many ways different from 2016. Back then, in the early going, Mr. Trump – a businessman and reality TV star – was a novelty act who shocked the GOP establishment, as when he called Mexicans rapists, criminals, and drug dealers in his announcement speech. Many Republicans didn’t take him seriously. Now, it’s clear anyone who discounts Mr. Trump does so at their peril.

And once again, Mr. Trump is playing a unique role. He’s the first defeated one-term president to run for his old office in modern history – and as such, there’s no road map. He is, in effect, a pseudo-incumbent, running to unseat an actual incumbent, each with a presidential record to run on.

Republican primary voters face a fateful decision. But it’s still early days. So far, Mr. Trump’s 2024 campaign has been remarkably low-key. Perhaps, some political observers suggest, his heart just isn’t in it; maybe he’ll change his mind about running.

Or, it may just be that he’s pacing himself. Some observers point to Mr. Trump’s influence in the 2022 midterms as a sign that he’s still very much in the game.

“They’re going to have this really crowded field, and tons of candidates that can’t really differentiate themselves from one another,” says Jennifer Lawless, a political scientist at the University of Virginia. “They don’t know if they’re Trump; they don’t know if they’re not Trump. We’ve seen that dysfunction play out in Congress.”

The fact that so many prominent Republicans are running against Mr. Trump, or preparing to run, is evidence enough that he’s vulnerable.

In her campaign debut this week, Ms. Haley – who served as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations under Mr. Trump – sought to thread the needle between distancing herself from her controversial former boss while also not attacking him. Her digs against Mr. Trump were indirect, as when she seemed to go after both him and the current president in her pitch for generational change.

“America is not past its prime. It’s just that our politicians are past theirs,” said Ms. Haley, who is in her early 50s. She also said she favored a “mandatory mental competency test for politicians over 75 years old.” Mr. Trump falls in that category, as does Mr. Biden.

She highlighted her parents’ background as immigrants from India, and her unique identity in GOP presidential politics as a woman of color. But Republicans, including Ms. Haley herself, are quick to say that their party doesn’t engage in “identity politics.”

“Republicans rebel against being told to vote for someone because of race, color, or religion,” says Chapin Fay, a GOP communications strategist in New York. Still, he adds, “Republicans want to expand the tent and live up to [former President Ronald] Reagan’s ideals.”

Indeed, the optimism that Ms. Haley sought to project in her campaign debut seemed to come right from the Reagan playbook. The “American era” hasn’t passed, she said. America is not a “racist country.”

But she also highlighted the culture war themes of race and education that have dominated the early going of the 2024 cycle – and have rocketed Mr. DeSantis to national prominence, and could also be Virginia GOP Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s calling card if he decides to run.

Ms. Haley, less widely known nationally than the Florida governor, may well have been smart to jump in first after Mr. Trump, earning several days of national media coverage. Her entrance drew relatively mild swipes from her former boss, whom she had once pledged not to oppose in a presidential race.

In an interview with Fox News Digital, Mr. Trump said he welcomed her to the race – even hinting at how the math works in his favor. “The more the merrier,” he said, adding, “I want her to follow her heart – even though she made a commitment that she would never run against who she called the greatest president of all time.”

The former president offered a sharper dig on Truth Social, calling her appointment to the U.N. ambassadorship in 2017 “a favor to the people I love in South Carolina” – i.e., getting her out of the governorship.

So far, Mr. Trump has not bestowed upon her a signature nickname. As more Republicans get in, however, he may feel duty-bound to deliver.

“Trump is in a kind of awkward situation,” says Dennis Goldford, a political scientist at Drake University in Iowa, which will hold the crucial first GOP nominating contest next year. “On the one hand, he takes it as personally offensive to him when people challenge him. But he also knows, the more the merrier.”

Some prominent Republicans note with disappointment that, in her announcement speech, Ms. Haley failed to mention the most courageous act of her governorship: removing the Confederate flag from the South Carolina State House grounds. The move, taken with bipartisan support, was a response to the 2015 massacre of Black parishioners by a white supremacist at a historically Black church in Charleston.

The issue of the Confederate flag remains fraught in the South, as some residents view it as a symbol of their heritage, not of racism.

Henry Barbour, longtime member of the Republican National Committee from Mississippi, says he became a Haley fan back in 2015 when the flag came down in Charleston.

“It was a powerful moment in South Carolina history,” Mr. Barbour says, noting that Mississippi removed the Confederate symbol from its own state flag in 2020. “It shows she’s willing to lead. ... She did the right thing. I’d encourage her to talk about that.”

Mr. Barbour is also a big proponent of highlighting diversity within the GOP, even while rejecting identity politics. The party is, in fact, diversifying, as seen in the slight uptick in the Black and Latino vote for Mr. Trump in 2020.

A message of inclusion will help the party win back some of the suburban voters it lost in 2016 and 2020, he says. “That’s where the aspirational message – addition versus division – helps us regain those lost voters.”