Biden and Democrats face up to biggest political liability: Inflation

Loading...

| Washington

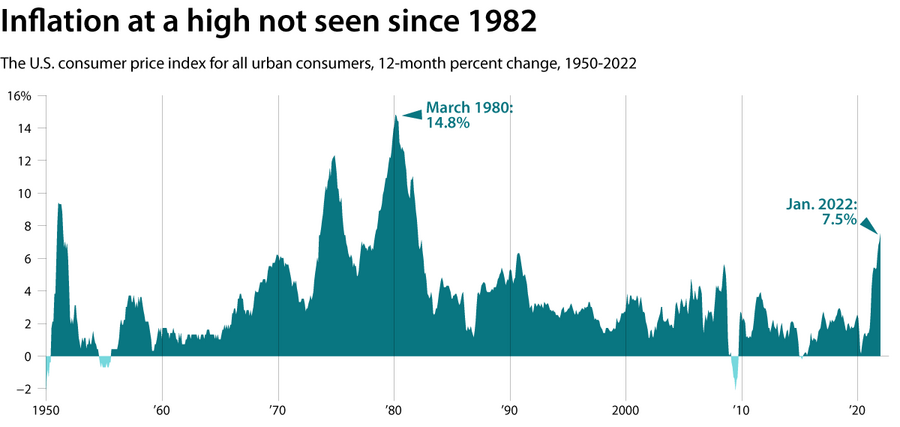

Inflation is running at an annual rate of 7.5%, the highest level in 40 years. And unlike other aspects of the economy that are currently strong – including low unemployment and robust growth – it touches everybody in a tangible way.

Whom do voters blame? Most often the party in power. With Democrats’ narrow House and Senate majorities already in major peril come November – and President Joe Biden’s approval ratings barely above 40% – high inflation only deepens the challenge.

Why We Wrote This

Inflation is an economic problem that touches nearly everyone – and voters tend to blame the party in power for it. President Joe Biden is trying to show empathy and make clear he’s taking the issue seriously.

Most economists concede there’s not much a president can actually do about inflation. Attempts to address pandemic-related problems with the supply chain, which contributed to some price spikes, have not been a panacea. But even if he can’t fix it, President Biden must be seen trying, Democratic strategists say. That starts with stronger public messaging – both expressing empathy, as some Americans struggle to pay higher bills, and continuing to pitch solutions.

“Inflation is very personal,” says Capri Cafaro, an executive-in-residence at American University’s School of Public Affairs and a former Ohio Democratic state senator. “When everything you buy is more expensive and your income is going less and less far, people are going to get frustrated.”

“It’s the inflation, stupid.”

That twist on the Bill Clinton-era slogan, ”It’s the economy, stupid,” could easily become the mantra for this November’s midterm elections. Inflation is running at an annual rate of 7.5%, the highest level in 40 years. And unlike other aspects of the economy that are currently strong – including low unemployment and robust growth – it touches everybody in a tangible way.

“Inflation is very personal,” says Capri Cafaro, an executive-in-residence at American University’s School of Public Affairs and a former Ohio Democratic state senator. “When everything you buy is more expensive and your income is going less and less far, people are going to get frustrated.”

Why We Wrote This

Inflation is an economic problem that touches nearly everyone – and voters tend to blame the party in power for it. President Joe Biden is trying to show empathy and make clear he’s taking the issue seriously.

Whom do voters blame? Most often the party in power. With Democrats’ narrow House and Senate majorities already in major peril come November – and President Joe Biden’s approval ratings barely above 40% – high inflation only deepens the challenge.

Most economists concede there’s not much a president can actually do about inflation. But even if he can’t fix it, President Biden has to be seen trying, Democratic strategists say. That starts with stronger public messaging – both expressing empathy, by acknowledging that some Americans are struggling to pay higher bills, and pitching solutions. Attempts to address pandemic-related problems with the supply chain, which contributed to some price spikes, have not been a panacea.

Until recently, Mr. Biden would bristle at media questions on inflation, muttering an expletive at a Fox News reporter last month, and last week calling NBC anchor Lester Holt a “wiseguy” for asking him what he meant when he claimed inflation would be “temporary.” Now the president and other top Democrats are making clear they take the problem seriously.

“There’s real inflation,” Mr. Biden said Tuesday in remarks to county executives. “If you’re in a working-class family, it hurts.”

He touted elements of his Build Back Better plan as a financial lifeline – including lowered prescription drug costs and subsidies for child care. The $1.7 trillion plan is stalled in Congress, and Mr. Biden has endorsed breaking it up and passing key pieces separately.

Politically, presidents live and die by the economy – though controlling inflation is the purview of the Federal Reserve, which operates independently of the White House. Chair Jerome Powell has signaled that the Fed is likely to start raising interest rates next month, in an effort to keep high inflation from becoming entrenched.

But even there, politics has entered with a vengeance. The president nominates members of the Fed’s board of governors, and this week, Republicans skipped a Senate committee hearing for five nominees – including Mr. Powell for his second term as chair – over objections to one.

In a call with reporters Wednesday, Democratic National Committee Chair Jaime Harrison accused GOP lawmakers of “actively trying to kneecap our economic recovery as we emerge from this global pandemic.”

Beyond the Fed and Mr. Biden’s fight to confirm board members in time for the March meeting, Democratic strategists say the president needs to be clear about what he can and can’t do, and to use his bully pulpit. His State of the Union address March 1 may be his best opportunity all year to get voters’ attention – and draw a contrast with Republicans.

“Americans will look at who’s trying to solve the problem and who’s just criticizing,” says Democratic consultant Karen Finney.

Since signing into law $1.2 trillion in infrastructure spending last November, Mr. Biden has traveled the country focusing on projects, including a trip to northeast Ohio today. Infrastructure spending doesn’t bring the immediate relief that voters are looking for on consumer prices, but it will create “a sense of economic momentum,” Ms. Finney says.

Speaking Thursday in Lorain, Ohio, which sits on Lake Erie, Mr. Biden touted a record $1 billion investment of federal infrastructure money to clean up sites in six states around the Great Lakes.

The funding will help make the water “safer for swimming and fishing, drinking, providing habitats for wildlife and wildfowl,” he said, adding that 40 million people get their drinking water from the Great Lakes.

Democratic strategist Jesse Ferguson points to polling by Navigator Research, which he advises, as showing some hope for Mr. Biden and his party. While voters are unhappy with Democrats’ economic performance, there’s room for growth among the many who favor the party’s economic agenda over that of Republicans.

“There are people out there who can be brought along on our economic record and agenda – if they hear about it,” Mr. Ferguson says.

Some Democratic lawmakers are looking for a quick, high-profile strike at rising prices: a pause in the federal gas tax, about 18 cents a gallon, for the rest of the year. The White House hasn’t endorsed the idea, but says “all options remain on the table.” Two vulnerable Democratic senators introduced legislation last week to suspend the tax.

But not all Democrats like the idea. It incentivizes the use of a fossil fuel, and there are concerns it could ultimately benefit producers of gas more than consumers. Some Democrats also express concern it could be hard to reinstitute the tax later. Former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers calls it a “gimmick.”

Professor Cafaro, the former Ohio state senator, is also not a fan. Right as the federal infrastructure law is kicking in, to limit funds to the federal trust fund that pays for highways and bridges sends a mixed message.

“From a practical standpoint, it’s shortsighted,” says Ms. Cafaro, who has served on state and national committees on transportation.

Another Democratic argument on inflation – that it’s the result of “corporate greed” – has been popular among progressive populists, but many economists are not buying it.

Veronique de Rugy, an expert on political economy at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, says greed can’t be ruled out in some instances. But it’s not the overarching reason prices are going up.

The real problem, she says, is that the policies of “fiscal accommodation” – sending people checks – “continued long past the time that the economy had recovered.”

“It took a while for people to recognize this, but there were a lot of voices, even on the left, saying, ‘Don’t do the American [Rescue Plan],’” says Professor de Rugy, referring to the $1.9 trillion pandemic relief measure passed early in the Biden presidency.

She mentions both former Secretary Summers and Jason Furman, the top economist in the Obama White House, as American Rescue Plan skeptics.

“It was too big,” she says. “What you end up with is really juicing the demand way too much.”