Why California’s governor is facing a recall vote. Three questions.

Loading...

| Pasadena, Calif.

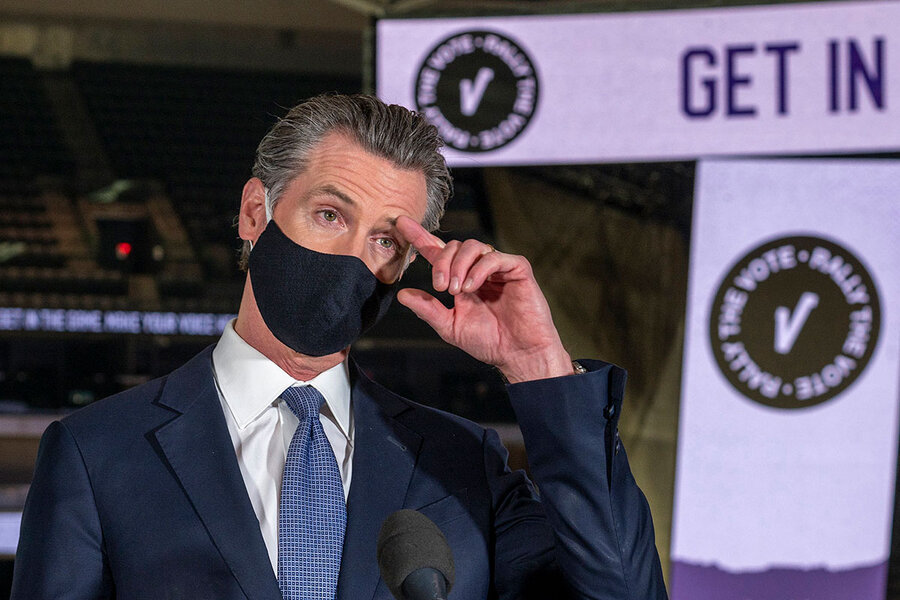

The tally is in. Opponents of California’s progressive governor, Democrat Gavin Newsom, have collected enough signatures – now verified by election officials – to trigger a recall election of the governor this year. Recall elections in the United States are rare. With 19 states allowing them, this will be only the fourth for a governor in U.S. history.

It’s going to be a biggie, and not just because California is a colossus. This is America’s main electoral event of the year, attracting national attention despite the likelihood that first-term Governor Newsom will prevail in this deep-blue state.

Why We Wrote This

The pandemic upended definitions of successful leadership at all levels. What was once seen as a long-shot bid – recalling California’s governor – is headed for a special election.

Since 1960, opponents have tried to recall every Golden State governor. They succeeded in getting enough signatures for a special election only once, in 2003, when voters removed Gov. Gray Davis, a Democrat, and replaced him with a Republican, celebrity Arnold Schwarzenegger.

The election is the first big test of how voters are feeling coming out of the worst health crisis in a century. Other governors will be watching.

“Usually, the question that voters ask is, ‘What have you done for me lately?’” says political scientist John Pitney. “The danger for Newsom is that they will pose another question instead: ‘What did you do to me last year?’”

The tally is in. Opponents of California’s progressive governor, Democrat Gavin Newsom, have collected enough signatures – now verified by election officials – to trigger a recall election of the governor this year. Recall elections in the United States are rare. With 19 states allowing them, this will be only the fourth for a governor in U.S. history.

It’s going to be a biggie, and not just because California is a colossus. This is America’s main electoral event of the year, attracting national attention despite the likelihood that first-term Governor Newsom will prevail in this deep-blue state.

“With special elections, weird things can happen,” cautions Jessica Taylor of the independent Cook Political Report.

Why We Wrote This

The pandemic upended definitions of successful leadership at all levels. What was once seen as a long-shot bid – recalling California’s governor – is headed for a special election.

Why do some people want to recall Governor Newsom?

Recall efforts are part of California’s political culture, but this one really picked up steam with the pandemic.

Since 1960, opponents have tried to recall every Golden State governor. They succeeded in getting enough signatures for a special election only once, in 2003, when voters removed Gov. Gray Davis, a Democrat, and replaced him with a Republican, celebrity Arnold Schwarzenegger.

The 2020 petition to sack Mr. Newsom was written before the pandemic. It faulted him on immigration, high taxes, high homelessness, and the death penalty. It didn’t gain much traction against a man who won the 2018 election with 62% of the vote.

But voters chafed under months of pandemic lockdown orders, empty classrooms, a clunky start to the vaccine rollout, and massive fraud with unemployment checks. They were particularly incensed when the governor ignored his own safety guidelines and dined with friends at an exclusive restaurant in November. Around the same time, a state judge threw petition-backers a lifeline – a four-month extension to gather signatures due to the pandemic.

“It was all kind of a perfect storm,” says Ms. Taylor.

Why should people outside California care?

The election is the first big test of how voters are feeling coming out of the worst health crisis in a century. Other governors will be watching.

Ms. Taylor believes governors will be judged on two things: vaccine rollout and if schools are reopening. Democrats fought hard to convert suburban women voters during the Trump era. Will they lose them over schools?

Even if schools are back in business in the fall, that may not matter, explains John Pitney, professor of political science at Claremont McKenna College in Claremont, California. This has been a traumatic year.

“Usually, the question that voters ask is, ‘What have you done for me lately?’” he writes in an email. “The danger for Newsom is that they will pose another question instead: ‘What did you do to me last year?’”

Not surprisingly then, the recall is attracting national political attention, money, and involvement from both sides.

What factors will determine the outcome?

There’s a slim chance the recall could be called off if Newsom supporters succeed in getting enough of the more than 1.62 million petition signers to formally change their minds. Assuming that doesn’t happen, voters will face two questions in an election likely to occur between August and December. The first will be “yes” or “no” on recalling the governor. The second question will be who should succeed him if he is recalled. In 2003, that list was long: 135 candidates. Whoever gets the most votes wins.

But as California pollster Mark Baldassare points out, 2021 is not 2003 (though the list could be similarly long). “The successful recall of the governor in 2003 occurred in a very different political context,” he writes in a blog about a March survey by the Public Policy Institute of California, which he leads.

A big difference is that in 2003, the governor was much less popular and the state less blue. Before the recall, Governor Davis had won reelection by 5 points; Governor Newsom crushed his GOP challenger, businessman John Cox, by 24 points. In 2003, Democrats led Republicans in voter registration by 9 points; today, the state is a much deeper blue, with registered Democrats leading Republicans by 22 points.

And back then, 70% of voters disapproved of Mr. Davis, particularly because of rolling blackouts in the state. In the March survey, fewer than half (42%) disapproved of the way Mr. Newsom is doing his job; 40% of likely voters say they will vote to remove him – a safe distance from the majority-vote threshold needed to remove. Meanwhile, 80% of voters said in March that the worst of the pandemic is behind them.

But anything can happen between now and the election – for instance, another record fire season and power outages. The governor just declared a drought emergency in two northern counties.

And of course, there’s the wildcard of the replacement candidates. So far, none of the main GOP candidates has the name recognition of former Governor Schwarzenegger – not former San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer, not Mr. Cox, and not former Rep. Doug Ose. But last week, a celebrity candidate jumped in the race: reality TV star, former Olympian, and transgender advocate Caitlyn Jenner, a longtime Republican.

Governor Newsom is already on the attack, tying her in fundraising emails to former President Donald Trump, who is unpopular outside of his base here. She's thin on issues compared to then-candidate Schwarzenegger.

Still, the GOP in California has a history of putting celebrities in political office: Ronald Reagan, Sonny Bono, Clint Eastwood. Could they do it again?