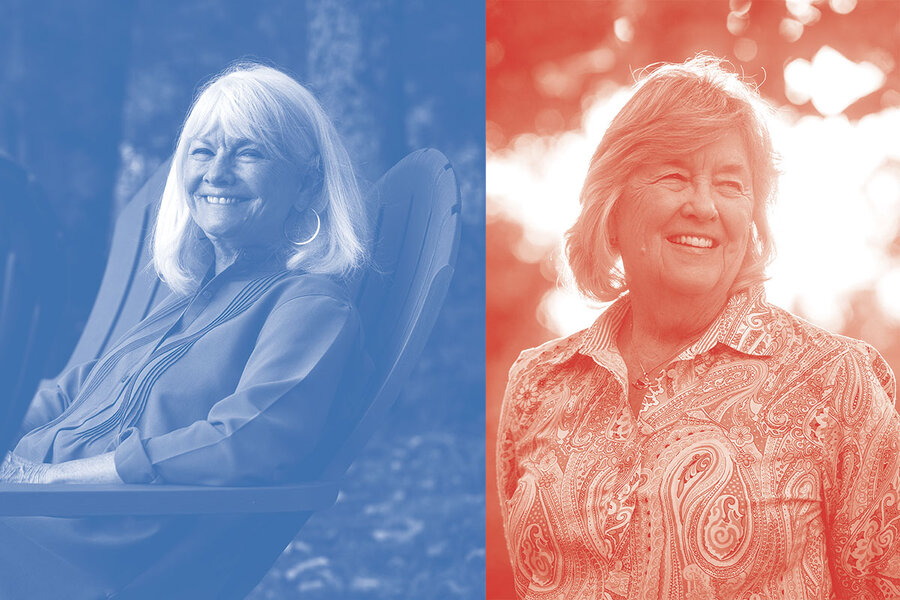

Can friendship be bipartisan? Ask the Janets.

Loading...

How will we ever be able to discuss politics with those who voted on the opposite side today? Ask the Janets.

Since joining the same sorority at the University of Southern California in the 1960s, they have navigated more than half a century of friendship as their careers, life experiences, and ZIP codes have caused their political viewpoints to evolve in different directions.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onAs the nation goes to the polls during one of the most fractious moments in U.S. history, two longtime friends who are ideological opposites show how a country can disagree with civility and respect.

Janet Nelson, an independent voter and business owner, admires how President Donald Trump stands up for America internationally and bucks political conventions at home. Janet Breslin, a Democrat who lived through the 1973 coup in Chile and joined her husband when he served as President Barack Obama’s ambassador to Saudi Arabia, worries that Mr. Trump exhibits strongman tendencies.

Yet through their ongoing discussions, they illustrate how two people can withstand the centrifugal pull of partisanship, gaining a deeper understanding of each other’s political views – even as they still wrestle with key issues and the man up for reelection today.

“Jan and I are some of the few people who kind of keep working this. A lot of people are like – forget it,” says Dr. Breslin, who chairs her local Democratic committee in New Hampshire. “We keep trying to convince each other.”

“I am prepared to give Trump the benefit of many doubts.”

It was Thanksgiving weekend 2016, and amid visiting with grandchildren at her lakeside New Hampshire home, Janet Breslin had just found a few quiet moments to reflect on the recent election in an email to Janet Nelson, one of her sorority sisters, in sun-christened California.

The two had met at the University of Southern California in the 1960s when some guys from a nearby town had recently launched the Beach Boys, “The Endless Summer” felt like a neighborhood documentary, and everything was looking up in the Golden State.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onAs the nation goes to the polls during one of the most fractious moments in U.S. history, two longtime friends who are ideological opposites show how a country can disagree with civility and respect.

One an international relations major, the other studying art, they bonded over building a papier-mâché volcano for sorority pledge week. It was the beginning of a lifelong friendship that would buoy them through personal crisis and political upheaval. They shared similar backgrounds: Each had roots in the Midwest, devout Christian parents, and similar arcs as young mothers. Yet their outlooks diverged dramatically as they settled on separate coasts.

So when the U.S. political scene erupted with the election of Donald Trump as president, the two Janets had much to discuss – and disagree about. Dr. Breslin, a Democrat who had lived through the 1973 military coup in Chile, taught at the National War College, and represented the United States alongside her husband when he was appointed ambassador to Saudi Arabia under President Barack Obama, was not immediately dismissive.

But she had a number of concerns that she laid out for Mrs. Nelson. “I can debate his policy positions ... but the chants and his own style and use of his wealth worry me,” she wrote in an email.

Mrs. Nelson, for her part, supported Mr. Trump in 2016 and still does today. An independent voter and business owner, she admires how Mr. Trump stands up for America internationally and bucks political conventions at home. She also likes that he’s not a career politician like Joe Biden.

“When Trump says he wants to clean up the swamp – I do, too,” she says, though she dislikes the way the president talks and wishes he would be a better role model.

On the eve of arguably one of the most consequential elections in U.S. history, the two Janets tell a story of America in a divided age.

Many people across the country who hold opposing views have found it difficult to preserve their relationships with friends, family, and even spouses. Some have cut off ties with acquaintances altogether. Others have unfriended people on Facebook or reached an uneasy peace by tacitly agreeing not to discuss politics. Forget about holding a thoughtful conversation about issues convulsing the republic.

A 2019 study revealed that fully 20% of Americans have experienced damage to a friendship as a result of political differences – and that’s based on data collected only a few months into President Trump’s administration.

The Janets, however, have navigated more than half a century of friendship as their careers, life experiences, and ZIP codes have caused their political viewpoints to evolve in different directions.

Over that time, the U.S. has seen a dramatic increase in polarization – more than many other major democracies. One 2020 study from Brown University attributes this to partisan cable news outlets and a political realignment over the past 50 years along racial and religious lines, which have resulted not only in greater differences between Democrats and Republicans ideologically but also in terms of identity.

Yet Dr. Breslin and Mrs. Nelson illustrate how two people can withstand the centrifugal pull of politics. Over more than half a dozen lengthy conversations with the Monitor, they offer insight into how they’ve preserved their friendship – and gained a deeper understanding of each other’s political views – even as they still wrestle with key issues and the man up for reelection on Nov. 3. While political disagreements, at times heated, have contributed to Dr. Breslin falling out of touch with other sorority sisters, she and Mrs. Nelson have maintained a strong bond.

“I don’t ever remember Jan and I ever being mad at each other about our different political views,” says Mrs. Nelson.

As the nation goes to the polls during one of the most fractious moments in history, the two Janets offer a template for how a country can disagree civilly.

“A good time to be alive”

Going to the University of Southern California was “like going to Mars” for Mrs. Nelson. Her parents came from Nebraska, where her grandfather was known to wrestle bears when the circus was in town to make an extra $50. In the hardscrabble farming community of Naponee, only one of his children made it past eighth grade – Mrs. Nelson’s father.

Her other grandfather had a stack of National Geographic magazines in his closet and a mind full of poems, which he would recite to little Janet as she followed him around the farm on extended visits. She and her cousins would jump into bins of cool corn kernels on hot days or play in the nearby stockyards and pretend to auction off the littlest kids and herd them into chutes.

Her parents settled in California and started a mobile home business. Their hard work paid off: Mrs. Nelson’s father went on to become one of the biggest West Coast dealers of mobile homes and would come back to visit Naponee in a shiny new Cadillac. But otherwise their life was modest, revolving around their Lutheran community, made up of bedrock people – plumbers, car salesmen, and insurance agents. By the time Mrs. Nelson entered USC, she didn’t know anybody who had been to college but her doctor, her pastor, and teachers in her Lutheran high school.

“I didn’t apply to college; my dad did,” says Mrs. Nelson. “He said, ‘You’re going to go to the best school I can afford.’”

At USC, she would meet another Janet with roots in the Midwest. Dr. Breslin was born in St. Louis, the oldest grandchild of Main Street Republicans. Her mother’s father was a civic booster who, apart from his beloved Oldsmobiles, put his money into supporting local projects like building a baseball field.

Her father’s mother went by the name Honey Bunch. Widowed as a young mother during the Depression, she started a boarding house after her husband died, bringing in enough income to support her four children.

In seventh grade, Dr. Breslin’s parents moved to Gardena, in Southern California, where her parents were active in their local Christian Science church. Her mother worked as a high school math teacher, and her father managed a savings and loan. He was a stalwart Republican. When President Richard Nixon was impeached and forced to resign over Watergate, he went to the airport to welcome him back to California.

She grew up thinking of Democrats as union people – and different from her. Then John F. Kennedy burst onto the national stage. He was “handsome as could be,” and in her eyes represented youth and the future.

“If I could vote, I would vote for Kennedy,” Dr. Breslin recalls telling her mother while watching the Democratic convention in the summer of 1960.

“I felt like we were on a roll,” she says. “We were going to go to the moon. It was a good time to be alive.”

A powerful bond

Dr. Breslin liked Mrs. Nelson the first time they met. She was fun but also sensible. She was creative – something Dr. Breslin admired because she wasn’t particularly creative herself. They quickly bonded and found in each other the sister neither of them had ever had.

After graduating from college, the two took different paths. Mrs. Nelson moved to Colorado to complete her student teaching, and her sorority sister went on to get a Ph.D. in political science at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Breslin then moved to Chile for a year with her husband. They lived through the 1973 military coup orchestrated by Augusto Pinochet that led to the torture, disappearance, and execution of thousands of Chileans over 17 years.

“Rule of law went away. Congress went away. Newspapers closed. The government implemented the use of torture,” says Dr. Breslin, who came away from the experience with an acute sense that liberty is fragile. “Without the constraints of law, the depths of action are almost unlimited.”

Dr. Breslin had a hard time conveying the brutality of what she saw in Chile to people in carefree California when she returned home.

“I felt the same way when I came back from Austria,” says Mrs. Nelson, referring to a University of Vienna program she participated in, during which she lived with an Austrian woman who had been forced to share her one-bedroom home with a Russian military family after World War II. “To have her describe what it was like to be on the other side of the Iron Curtain ... how do you explain that to somebody who is in college in California with the Beach Boys?”

Dr. Breslin decided to get a job on Capitol Hill to help keep America’s democratic system strong. She worked for a series of Democratic senators, focusing in part on a rising issue at the time – immigration.

Back in California, Mrs. Nelson was dealing with the same issue in a different way. She was on the front lines of Hispanic immigration in public schools. On Dr. Breslin’s visits to California, she would ask who would work in the agricultural fields if not immigrants.

But Mrs. Nelson, who taught art and then went on to work in special education after getting a master’s degree, told her friend that many of her low-income students couldn’t get jobs. The entry-level positions were being taken by immigrants who had crossed the border illegally. And families from Mexico and Central America who had gone through the legalization process were adamantly opposed to the surge in illegal immigration.

“In California, we’ve had a huge problem forever, which Jan didn’t really understand. She still thought of California as being like when she was growing up here,” says Mrs. Nelson, who taught at a high school in Westminster where students spoke 27 languages. “But it had started to change. She just didn’t have a clear picture of what we were going through.”

During one memorable lunch, one of their other sorority sisters told Dr. Breslin she was prepared to defend her beach town against the influx of immigrants.

“She sounded like a Bosnian, talking about it. I’m speaking lightly of it, but that’s a powerful feeling,” says Dr. Breslin, who says her time in Saudi Arabia gave her a greater understanding of how powerful culture can be, especially when people feel it’s being invaded. “I stand in respect for how powerful those feelings are. And I didn’t respect it at the time, because I didn’t understand it.”

But even as the two Janets’ political views were moving in different directions, when personal crises struck, they turned to each other. At one point, Dr. Breslin confided in her sorority sister about the dissolution of her marriage, which left her with a baby, a 4-year-old, and a demanding job in a fast-paced and at times unforgiving Washington, D.C.

Mrs. Nelson could relate to her ordeal. Her husband, who had been her high school sweetheart, had come home one day and, as she recalls it, announced, “I don’t want to be a father, and I don’t want to be married, and I don’t want to be here.” He packed a suitcase and left. She says she was totally blindsided.

“So that’s a powerful thing to share with each other,” says Dr. Breslin.

Decades later, their devotion to each other remains strong. “If I have a personal problem, Jan is going to be the first person I’m going to talk to,” says Mrs. Nelson.

Tough conversations

The closest their relationship ever got to a breaking point was over a series of chain letters. Mrs. Nelson would frequently forward to Dr. Breslin emails she got that included false information and breathless assertions in all-caps, setting off a flurry of frank exchanges.

Bill Clinton wants to take away all your guns, claimed one. “I would dutifully do research and go, ‘Janet, President Clinton does not want to take away your guns,’” says Dr. Breslin. “Whatever the rumor was, I would do all this research.”

Another chain message, with the subject line “Good Info,” asked whether a series of statistics were about the NBA or the NFL:

14 have been arrested on drug-related charges; 8 have been arrested for shoplifting; 21 currently are defendants in lawsuits. And 84 have been arrested for drunken driving in the last year. “Can you guess which organization this is?” it asked. “Give up yet? Neither, it’s the 535 members of the United States Congress. The same group of Idiots that crank out hundreds of new laws each year designed to keep the rest of us in line.”

Dr. Breslin’s reply was brief this time. “No no no.” She saw in the emails a troubling pattern of undermining trust in America’s democratic institutions.

Then came the emails claiming that Mr. Obama’s birth certificate from a hospital in Hawaii was inauthentic – a topic Mrs. Nelson took particular interest in since she, too, had been born in Hawaii. Her father had helped recover the bodies of American soldiers after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

“It made me really sad that Jan would believe that,” says Dr. Breslin, who continued to refute such emails. “Jan is a reasonable, thoughtful, smart woman. But whatever I did had no impact. None.”

Mrs. Nelson disagrees, emphasizing how much she valued her friend as a sounding board. “One of the reasons I sent you the chain mails that I was getting,” says Mrs. Nelson in a joint interview, “is because I respect hugely your political knowledge and also to have you see what’s happening with our friendships and the things we’re dealing with on our end of the world.” Mrs. Nelson would sometimes share Dr. Breslin’s responses with mutual friends who had forwarded her the emails.

Indeed, as frustrating as such exchanges have been at times, they have pushed both women to better understand the other’s point of view.

“What I thought about and I’m still thinking about ... is what are those things that were touching something deep in [you], either your experience by teaching in the LA city schools or that you saw culturally happening in Los Angeles that I needed to be more attentive to?” asks Dr. Breslin.

She was gaining a better appreciation for why some people in California were so resentful of the latest surge in immigration. She wasn’t surprised when Mr. Trump made it such a central part of his campaign in 2016. “He has great political instincts,” Dr. Breslin admits.

His tough stance on immigration is one of the things that first resonated with Mrs. Nelson. “When I look at our president and the things that he does – it irritates the heck out of me, but at the same time, I appreciate him being firm in ways that other presidents were lax,” says Mrs. Nelson, who runs an oral hygiene education company, Toothfairy Island, whose materials are used in schools across the U.S. as well as in a number of other countries. “I think we need more firmness.”

At Dr. Breslin’s urging, Mrs. Nelson researched more than two dozen Democratic candidates running for president early in the 2020 campaign to see if she could support any of them. But she found that none was willing to put what she considered meaningful boundaries on abortion, which was a deal breaker for her. As someone who lost two children to miscarriages, she says she would never want any other mother to hurt the way she did, ending up without that child.

“You don’t want anyone else to go through that pain and regret,” says Mrs. Nelson. “Especially when they’re young and they make decisions, they don’t really understand the impact it has on them.”

For Dr. Breslin, who now attends a Lutheran church and chairs her local Democratic committee, the challenges of the Trump era go beyond personality to an erosion of founding principles and shared values. She worries he could destroy the delicate balance of power designed by the framers to prevent tyranny.

“It’s not just President Trump. It’s what he has touched in people that made them abandon the values I thought we were all raised with,” says Dr. Breslin, who describes deep anger and a gradual toughening – on both sides of the aisle. “I think we’re both addicted to it, or stuck. We’re in a rut. A dangerous rut.”

Across the nation, that polarization is not only affecting personal relationships, but also dividing communities and professions, says Dr. Breslin. And she feels that President Trump is exacerbating those divisions by caricaturing people like her.

“He’s telling people ... [Janet] hates this, and she’s against this, and she’s a lefty, and all these things – and I feel like saying, ‘No I’m not,’” says Dr. Breslin. “I don’t hate [Mr. Trump] at all, but I really, truly believe he feels it’s useful to hate me.”

Mrs. Nelson, for her part, has refused to play into such rhetoric. “What keeps me going and being hopeful always is I believe that God is in charge,” she says.

Even so, neither of them plans to stop sending missives about policies and politicians they see differently.

“Jan and I are some of the few people who kind of keep working this. A lot of people are like – forget it,” says Dr. Breslin. “We keep trying to convince each other.”