White working class is shrinking. It still may decide 2020 election.

Loading...

| Scranton, Pa.

Nationally, white voters without college degrees are a shrinking portion of the electorate. Yet in critical battleground states like Pennsylvania, they still represent a majority of voters. Because President Donald Trump’s approval has dropped significantly in the suburbs, he likely needs to grow his support among this demographic.

In theory, he has room to do that. According to Dave Wasserman of the Cook Political Report, 66% of all eligible citizens who did not vote in Pennsylvania in 2016 were non-college-educated white adults. And over the past four years, Republicans have been outpacing Democrats among new voter registrations in the state.

Why We Wrote This

Working class voters from Rust Belt states were key to the 2016 election – and may yet decide 2020. Four years later, their concerns are the same: jobs and a future for their kids. But who do they feel best represents their values?

But Democratic nominee Joe Biden is making a direct play for these voters as well. The former vice president has been careful to walk a more moderate line on issues like fracking, and has emphasized his own hardscrabble childhood in Scranton. That’s making the president’s path to victory more challenging.

“We value our values here, and that’s why we love Joe,” says Jimmy Connors, who was Scranton’s mayor from 1990 to 2002, serving as a Republican for all but two of those years.

Almost every morning, half a dozen men meet for coffee at Max’s Deli, a diner that shares a wall with an auto supply shop, to talk politics. Some live “up the line” or “down the line” – a reference to the historic Scranton railway – but all have lived in the area their entire lives. And come Nov. 3, all are planning to vote for President Donald Trump.

“I’ve never really been political up until this last election,” says Bob Duffy, an Air Force veteran and retired mailman. He expresses some distaste for the president’s personal behavior, saying “I don’t care for his attitude.” But he still believes Mr. Trump is suited to the job: “He’s the type of man we need for this political age.”

“I’m all for him,” agrees Al Gordon, a veteran as well. “He’s finally standing up to China for a change, and standing up to all these countries that have been taking our money.”

Why We Wrote This

Working class voters from Rust Belt states were key to the 2016 election – and may yet decide 2020. Four years later, their concerns are the same: jobs and a future for their kids. But who do they feel best represents their values?

Four years ago, voters like Mr. Duffy and Mr. Gordon propelled Mr. Trump to a surprise win here in Pennsylvania – and, by extension, the Electoral College. Mr. Trump’s success in formerly Democratic-leaning Rust Belt states, including Michigan and Wisconsin, sent media outlets scrambling to places like Max’s Deli outside Scranton to try to better understand why white working-class voters had so fervently embraced the brash real estate mogul from New York.

Now, as the nation hurtles toward one of the most contentious and unusual elections in modern history – in a year marked by a pandemic, mass unemployment, and social and racial turmoil – Mr. Trump’s hopes for a second term may hinge once again on the support of these same voters. The big question is whether they will back the president with equal or even greater levels of intensity this time around. And whether it will be enough.

Nationally, white voters without college degrees are a shrinking portion of the electorate, going from 45% in 2016 to 41% now. Yet in a number of critical battleground states like Pennsylvania, they still represent a majority of voters. Because the president has seen his approval drop significantly in the suburbs, he likely needs to grow his support among this demographic.

In theory, Mr. Trump has room to do that. According to Dave Wasserman of the Cook Political Report, 66% of all eligible citizens who did not vote in Pennsylvania in 2016 were non-college-educated white adults – more than the state’s Black, Hispanic, Asian, and college-educated white non-voters combined. And over the past four years, Republicans have been outpacing Democrats among new voter registrations in the state.

But Democratic nominee Joe Biden is making a direct play for these voters as well. The former vice president has been careful to walk a more moderate line on issues like fracking, and has emphasized his own hardscrabble childhood in Scranton. That’s making the president’s path to victory more challenging.

So far, “polls show Trump is winning a smaller percentage of non-college whites than he did in 2016,” notes Mr. Wasserman. “For every one of those voters who defect from Trump to Biden, Trump needs to bring out two [new] voters to offset that.”

Still, the fight for one of the nation’s largest swing states is not a done deal. After all, many point out, Mr. Trump was behind in Pennsylvania polls four years ago, and wound up winning.

“Trump can’t afford to lose anything here,” says Joseph Sabino Mistick, a law professor at DuQuesne University and Sunday columnist for the Pittsburgh Tribune. “But Biden’s always been a hero of the working class – and this creates a dilemma for Trump in Pennsylvania.”

The Keystone State

In mapping out various paths to 270 electoral votes, no state may be more critical to both candidates than Pennsylvania. To put it another way, it’s difficult to envision either candidate ultimately winning the Electoral College without it.

President Trump won Pennsylvania – the first Republican presidential candidate to do so in more than three decades – by fewer than 45,000 votes in 2016. Since then, he’s held more rallies here than in any other state aside from Florida, including one just this week in Erie.

Mr. Biden seems equally determined to win the Keystone State. In addition to playing up his connection to Scranton, he has based his campaign headquarters in Philadelphia, and has used Pittsburgh as the site for several nationally televised addresses. His former boss, President Barack Obama, chose Philadelphia as the site for his first “drive-in rally” in a return to the campaign trail this week.

In some ways, Pennsylvania’s politics can be seen as a microcosm for the United States as a whole. Cities densely populated with diverse, college-educated liberals seem a world away from the state’s rolling rural counties of mostly white, non-college-educated conservatives.

As elsewhere, the suburbs in between have dramatically shifted from red to blue in recent years. Pennsylvania’s suburban voters now favor Mr. Biden by 38 percentage points over Mr. Trump, according to a recent Washington Post-ABC News poll. That’s 25 points higher than Hillary Clinton’s margin four years ago.

Much of that shift has been driven by suburban women – whom the president has lately taken to pleading with directly. “Suburban women, will you please like me?” he joked at a rally last week in Johnstown. “Please. Please.”

Some political experts think Mr. Biden’s lead in the suburbs will be enough to hand him the presidency outright. Indeed, Mr. Biden currently leads in Pennsylvania overall by an average of 6 percentage points, according to FiveThirtyEight.

“People always talk about the white working-class vote. What about the women who shop at Trader Joe’s?” says Robert Lang, a professor of public policy at the University of Nevada Las Vegas and co-author of the book “Blue Metros, Red States.” “In 2016, there was complacency in suburban Philly – and now, voters there report to pollsters they would walk over glass to vote.”

Still, that assumes Mr. Trump doesn’t find a way to grow his support in small town and rural areas, either by expanding his 30-point 2016 margin of victory among Pennsylvania’s white working-class voters, or by drawing more of those voters to the polls this time around. He may need to do both.

Swing counties

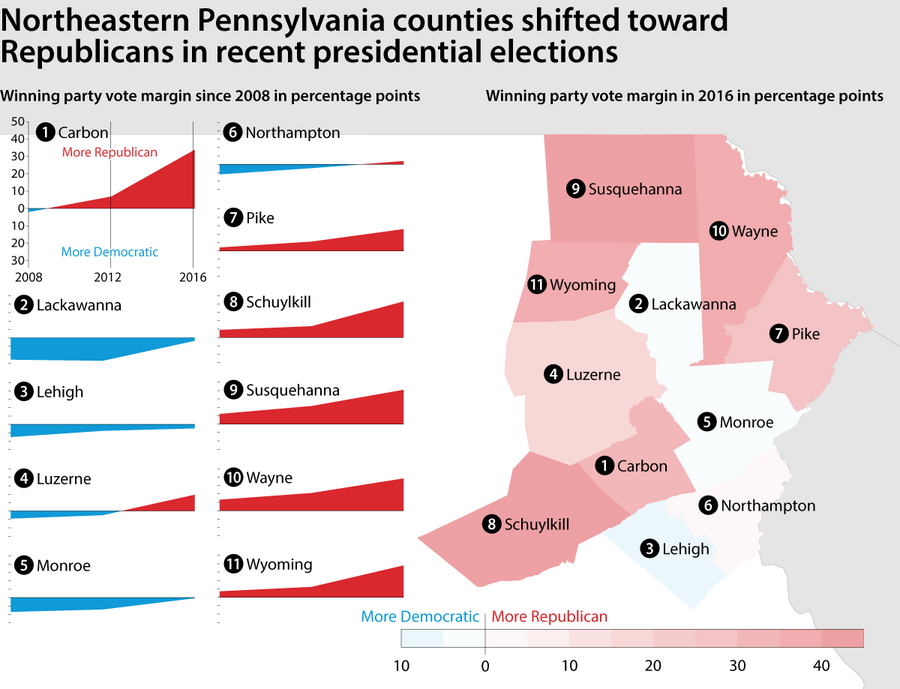

Pennsylvania’s key swing region is the right tip of the “T” between Scranton and Allentown, which is home to two of the state’s three “pivot counties” that twice voted for Mr. Obama before voting for Mr. Trump. Luzerne County swung from a nearly 9-point margin for Mr. Obama in 2008 to a 19-point victory for Mr. Trump. And while neighboring Lackawanna County, home to Scranton, stayed blue, the margin was alarming for Democrats. After Mr. Obama’s more than 27-point win in 2012, Mr. Trump lost here by fewer than 4 percentage points.

“The people here are very frustrated with the lack of progress that we’ve seen in the past 40, 50 years,” says Gary Wegman, a Democrat running in the 9th Congressional district. “They want to see their communities be able to compete like the rest of the world. They’re tired of being on an uneven playing field.”

When asked to describe themselves, northeastern Pennsylvanians offer adjectives like: hardworking, friendly, working class, and honest. The area was once defined by its anthracite coal mines, and the immigrant populations who came here to work in them. But the number of mining jobs have decreased, as have manufacturing jobs. Now it’s hard to even make a profit farming, says Dr. Wegman, who is both a fifth-generation farmer and a dentist.

Before COVID-19 disrupted the national economy, Pennsylvania had an unemployment rate of 12%, higher than the country as a whole. And counties in the northeast region – Lackawanna, Luzerne, Susquehanna – had rates higher than the state average. This year, following the pandemic, the statewide unemployment rate set a four-decade record.

“I just decided years ago that my two kids aren’t going to have the same opportunities that I did. It just gets chipped away more and more each year,” says John Kameen, chair of the Susquehanna County Committee to Re-elect President Trump. This economic frustration, he says, has gradually pushed the area’s residents away from the Democratic Party.

Between 2012 and 2016, Republican voter registration increased by more than 7% in Lackawanna County, more than 14% in Luzerne County, and more than 5% in Susquehanna County. Between 2016 and this month, these three counties have witnessed similar increases. Meanwhile, Democratic registration in these counties has decreased since 2012.

Mr. Kameen, who has been involved in Susquehanna County politics for over 50 years, says local enthusiasm for Mr. Trump in 2016 was unlike anything he had ever seen. And he insists this year is surpassing it. At the local GOP headquarters, he says they routinely run out of Trump-Pence lawn signs – and have sold at least 20 4-by-8-foot ones. “A guy came yesterday and said he wanted five,” he says.

Dr. Wegman, the Democratic congressional candidate, says he wasn’t surprised that Mr. Trump did well in northeast Pennsylvania in 2016 – because he spoke directly to voters’ concerns.

“I saw what [they] were listening to, and I understood,” he says. He knows plenty of people who want to work but can’t find jobs. He agrees that the immigration system needs reform.

And while he thinks Mr. Biden is the candidate who would best deliver on all these issues, he hopes the former VP can convince enough of his northeastern Pennsylvania neighbors of that.

“You want to win Pennsylvania, you’ve got to come in here to the ‘T,’” says Dr. Wegman. “[Biden’s] going to win Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. But are there enough votes there? Ask Hillary.”

“We value our values here”

At the Lackawanna County Democratic headquarters in Peckville, five women sit around plastic folding tables, sharing pizza and soda. They all have friends who voted for Mr. Trump – either because they hoped he would bring back jobs, or because he wasn’t Mrs. Clinton. But they say it’s now clear that the president has only made things worse.

“I think the working-class people who thought they were going to get a change with him are going to be looking at it now and saying, ‘No, I’m not any better,’” says Ann McDonough, a retired teacher who was born and raised in Scranton. “I think people got fooled by him. I know I paid more taxes.”

Ms. McDonough volunteers at the Peckville office on weekday afternoons – a level of political involvement she says she’s never had before. She periodically interrupts herself to welcome locals who wander in, handing out signs for Democratic candidates up and down the ballot.

She and the other women speak of a widespread fatigue in the area.

“People are tired,” says Mary Ann Kapacs, former chair of the Lackawanna County Federation of Democratic Women. “I’ve stopped watching the news because it’s just too upsetting. And combined with the quarantine and everything,” she trails off. “It just makes you feel bad inside.”

Mr. Trump’s personal behavior goes against the values they were taught as children growing up here, the women say – which is one reason Mr. Biden’s early years in Scranton mean something to them.

“We value our values here, and that’s why we love Joe,” says Jimmy Connors, who was Scranton’s mayor from 1990 to 2002, serving as a Republican for all but two of those years.

When asked why he thinks Mr. Biden would be a good president, Mr. Connors at first references policy positions. But he also mentions Mr. Biden’s Amtrak commute from Washington to Delaware each evening back when he was in the Senate so he could be with his family.

“Can you see Trump doing that? That’s the difference between [Trump] and what Biden learned at his kitchen table here in Scranton,” says Mr. Connors. “Biden is Scranton.”