Is Trump draining the swamp – or is the water rising?

Loading...

| Washington

Donald Trump first uttered the rallying cry “drain the swamp!” just three weeks before the 2016 election. Promising to “make our government honest once again,” Candidate Trump unveiled a five-point proposal aimed at reining in the influence of lobbyists.

“Drain the swamp!” quickly became one of Mr. Trump's central campaign promises – and one of the most popular chants at his rallies.

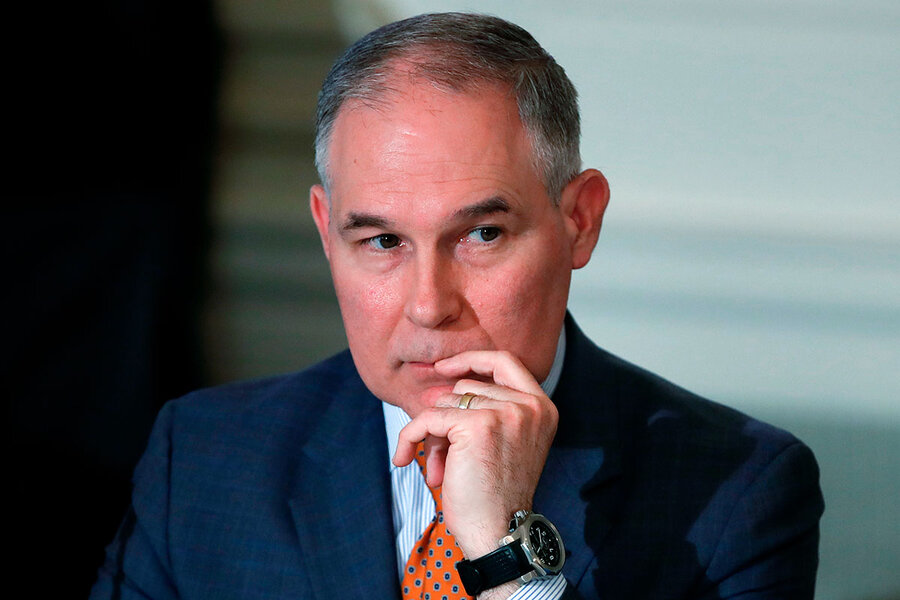

Today, experts on government ethics say, President Trump is presiding over one of the most ethically challenged administrations in modern history, especially this early on. Scott Pruitt, head of the Environmental Protection Agency, is only the latest example of a cabinet member operating under a storm cloud. Most recently, Mr. Pruitt has been accused of an improper housing set-up connected to an energy lobbyist, unconventional pay raises to favored political appointees, and reassignment or demotion of senior staff who questioned his spending. His job reportedly hangs in the balance, amid mixed signals from Trump and his spokespeople.

Other Trump cabinet members have already gotten the heave-ho, after questionable spending came to light. Former Veterans Affairs Secretary David Shulkin, fired last week, had faced criticism over travel expenses for a trip to Europe, including airfare for his wife, which he says he repaid. Mr. Shulkin, who had also served as an under secretary in the Obama administration, maintains he was let go because he resisted pressure from the Trump White House to privatize veterans’ health care.

All presidents deal to some extent with alleged wrongdoing by senior appointees, but “I have never seen anything like this,” says Scott Amey, general counsel for the Project on Government Oversight, a nonpartisan government watchdog group.

Why is this happening, especially under an outsider president who swooped into Washington promising to change the way the capital operates?

One answer may center on what, exactly, Trump meant by “drain the swamp.”

Focus on deregulation

“We thought he was saying, ‘Hey, there’s going to be a new sheriff in town,’ and that he would do things differently with the revolving door [between government service and lobbying] and cleaning up ethics laws and regulations,” says Mr. Amey.

But so far, draining the swamp has been more about deregulation and shrinking the federal workforce, and less about strengthening or even adhering to the norms and rules of ethical behavior for government officials. Trump’s attacks on the media and on entrenched members of Congress – of both parties – have also tended to label them as members of the “swamp.”

Of the proposals in Trump’s original five-point plan, only one is fully in place: an executive order barring executive branch officials from lobbying for foreign governments or parties after they leave the administration.

The president’s own behavior has been important in setting the tone for his team, political analysts say.

Trump has yet to release his tax returns, defying the customary practice of modern presidents. He faces multiple lawsuits over his businesses and whether the income he derives from them violates the Constitution’s emoluments clause, which forbids the receipt of gifts from foreign countries. A federal judge ruled last week that one of the lawsuits can proceed. Trump’s business dealings are also under scrutiny as part of special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 election and whether the president colluded with the Russians or engaged in obstruction of justice.

Besides Pruitt and Shulkin, multiple Trump cabinet secretaries have found themselves in hot water: Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson, and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin have all faced questions about their use of taxpayer money. In addition, Trump’s first secretary of Health and Human Services, Tom Price, was fired after just seven months on the job, following reports that he had spent $1 million in federal funds on private jet travel.

Not that members of the federal bureaucracy are above reproach. Former FBI deputy director Andrew McCabe was fired last month after the FBI’s Office of Professional Responsibility found he had leaked to the media and “lacked candor” under oath, charges he denies.

Question of experience

But the swarm of ethics allegations facing Trump’s team is unusual. It may well reflect the fact that Trump is new to public service and came into office under his own ethical cloud, says Mickey Edwards, a Republican from Oklahoma who served in Congress from 1977 to 1993, including a stint in the leadership.

“I think some of [Trump’s appointees] came in with a sense of, ‘We’re now the bosses, and we can get away with whatever,’ ” says Mr. Edwards, now a vice president at the Aspen Institute and author of the book “The Parties Versus the People: How to Turn Republicans and Democrats into Americans.”

Like Trump, some appointees entered the cabinet with no prior experience in public office. Secretary Carson, at HUD, was a renowned surgeon, and ran briefly for president in 2016, before becoming a prominent defender of Trump and then a cabinet secretary. The purchase of a $31,000 dining set for Carson’s HUD office set off an uproar last month; he has testified that he was not involved in the purchase, and canceled it.

Secretary Mnuchin, a former investment banker and film producer, faced criticism last fall when the Treasury Department’s Office of Inspector General found that seven flights he had taken on military aircraft had cost the federal government more than $800,000. The report stated that no laws were broken, but criticized the use of federal funds all the same.

But other Trump appointees came to the administration with extensive experience in government, either as members of Congress or in state government. All have previous experience working under governmental ethics rules. Before coming to Washington, Pruitt was attorney general of Oklahoma and before that, a state senator.

Kind words for Pruitt, but ...

Both Carson and Mnuchin seem to have weathered their storms. But Pruitt may not. Trump still praises him publicly – he’s doing a “great job,” the president tweeted on Friday – but such kind words are no guarantee of job security. According to news reports, chief of staff John Kelly advised Trump last week to fire Pruitt, though Trump wasn't ready to let him go at that point. Friday morning, Trump and Pruitt met.

The dilemma for Trump is that, as head of the EPA, Pruitt is doing exactly what the president wants – rolling back environmental regulations that he says have been holding back economic growth. Three Republican members of the House have called for Pruitt’s resignation. But prominent conservatives have defended him, including Sens. Ted Cruz of Texas and Rand Paul of Kentucky.

Senator Paul tweeted Thursday that Pruitt is “likely the bravest and most conservative member of Trump’s cabinet” and is needed to help Trump “drain the regulatory swamp.” Senator Cruz, in a tweet, blamed “Obama and his media cronies” for wanting to drive Pruitt out.

Conservative talk radio host Rush Limbaugh opened his show Thursday with a full-throated defense of Pruitt, blaming the liberal “deep state” for attacking the embattled EPA administrator. Mr. Limbaugh, with millions of listeners, has broad power to influence public discourse among Trump supporters.

Other conservatives speak of a “witch hunt” against Pruitt – the same language Trump uses when speaking of the Mueller investigation.

“The ‘witch hunt’ meme comes from the top, and is applied to anyone who disagrees with the president,” says James Pfiffner, professor of public policy at George Mason University. “Instead of confronting the issue, or arguing against the allegations, they resort to name calling. It is very sad.”