How Hillary Clinton learned to become a street fighter

Loading...

| Washington

In 1999, when Hillary Clinton announced her first run for office – a campaign for US Senate – New Yorkers were skeptical.

She’s not one of us; she’s a carpet-bagger, they said. Born and raised in Illinois, educated in Massachusetts and Connecticut, then a transplant to Arkansas before taking up residence in the White House, Mrs. Clinton had no obvious connection to New York. But the then-first lady embarked on a “listening tour” and never looked back.

“She became the local girl,” says pollster John Zogby, based in Utica, N.Y. “She did town meetings, she did the famous listening tour, and she impressed people with the fact that she actually listened. She would stay till the last person left.”

And she won, making history as the first wife of a president to run for (and win) public office. Six years later, Clinton easily won reelection.

Winning the presidency is many orders of magnitude more difficult than winning a Senate seat. Performing for the cameras is crucial, and that’s not Clinton’s strength. She has said as much, admitting that she’s not a “natural politician” like her husband or President Obama.

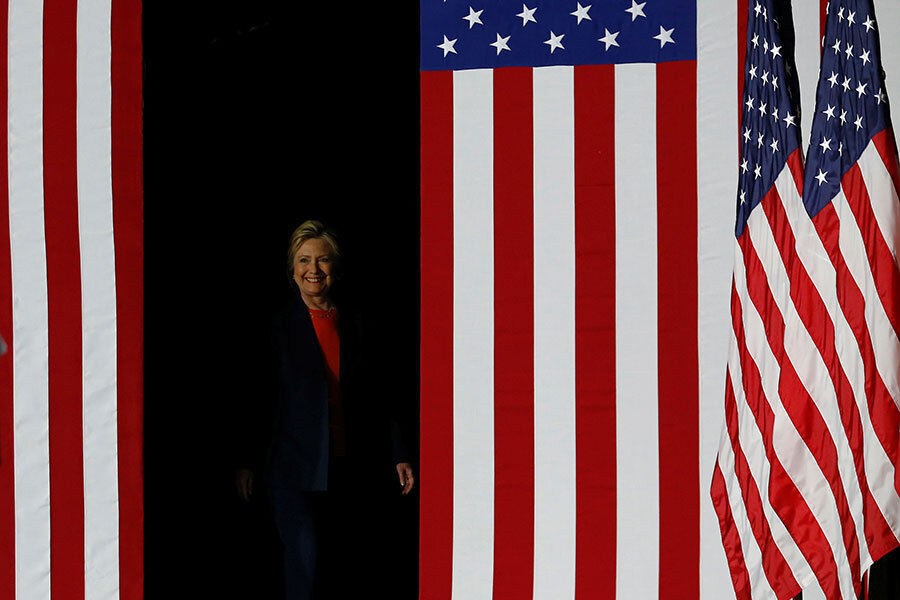

But Clinton may have found a way around that. In her big speech Thursday in San Diego – ostensibly on foreign policy, but really, a takedown of Donald Trump – the former secretary of State showed that she can deliver a sharp message without descending into Trumpian petulance and name-calling.

Clinton called Mr. Trump “thin-skinned,” his ideas “dangerously incoherent.” And she did so in a tone that was sober and serious. At times, audience members laughed – such as when she said that “there is no risk of people losing their lives if you blow up a golf course deal” – but she never laughed along with them. At most, she offered a knowing smile.

But Clinton made her point – that she’s ready to do battle with the most unorthodox of general election opponents in modern history.

“She has fully realized that she has to get into the trenches,” says Mr. Zogby. “She’s had to become a street fighter.”

Going forward, Clinton’s biggest challenge in going up against Trump is to maintain her focus on the issues that she wants to talk about.

“The point is, you can’t beat him at his own game – of invective and innuendo and slander,” says Cal Jillson, a political scientist at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. “You have to point to it, you have to decry it, you have to describe it as a prohibition on real discussion of real issues, then get back to those issues and talk about them in your own terms.”

The reality, though, Mr. Jillson acknowledges, is that Trump is going to cry “Crooked Hillary” at every opportunity – and that there’s a running narrative about Clinton that gives him plenty of fodder. There’s Clinton’s use of a private e-mail server while secretary of State. There’s her handling of the 2012 attack on the United States mission in Benghazi, Libya. There’s the family foundation and allegations that it traded “dirty money” for access. There are all the old controversies from her husband’s presidency.

Clinton can’t just ignore Trump’s charges of “crookedness,” says Jillson, especially when the relevant issues make headlines. Last week, for example, the State Department inspector general released an 83-page report highly critical of her e-mail practices during her time as secretary of State. Sometime in the next few weeks or months, the Federal Bureau of Investigation is expected to complete its own investigation into the e-mails. Whatever comes of that will be a major milestone in the campaign.

So the challenge for Clinton will be to balance responding to Trump without allowing the campaign to proceed entirely on Trump’s terms.

The perceived wisdom is that Trump is an unconventional candidate, and that the American people are in a wholly different place from where they usually are – and therefore the usual Democrat versus Republican playbook won’t work. But some Democrats believe that argument is overstated.

“When you come down to it, we’re electing a president here,” says Democratic strategist Peter Fenn. “This isn’t ‘Celebrity Apprentice.’ I guess I have a fundamental faith that the American people are going to be able to sort this out.”

Mr. Fenn offers a bottom line: Practically every campaign is about change or fear of change, and while Trump is presenting himself as a change agent, it’s not entirely clear what he means by that. So Clinton’s argument, he says, is “hold on a minute, what are we really going to get with Trump?”

That was the point of Clinton’s speech Thursday – not to unveil any new foreign policy ideas or spend much time defending her four years as secretary of State, but to invite Americans to imagine a Trump presidency. She raised the specter of a trade war with China, and questioned Trump’s expressions of admiration for “dictators” like Russian President Vladimir Putin.

“This is not someone who should ever have the nuclear codes, because it’s not hard to imagine Donald Trump leading us into a war just because somebody got under his very thin skin,” she said.

Clinton’s speech won praise from Democrats, because she showed that she was willing to stand up to Trump – but didn’t try to play his game. She didn’t dub him “Dangerous Donald,” even if she implied it. Clinton’s new game is to play street fighter, in her own way.