Presidents' Day 2013: How a Senate tradition keeps George Washington’s words alive

Loading...

No matter how Americans choose to celebrate Presidents’ Day – whether cashing in on big sales or participating in family outings – the third Monday in February was traditionally intended as a day to celebrate the birth of President George Washington and honor his legacy.

In addition to the three-day weekend, the US Senate has its own custom for honoring America’s first president: Every year since 1896, a senator has been selected to read Washington’s Farewell Address during legislative session.

On Sept. 19, 1796, Washington proclaimed to his “Friends and Fellow-Citizens” that he intended to retire after his second term, setting the precedent for two-term limits. He also used the occasion to bestow on the nation his vision for enduring democracy.

He wrote, “a solicitude for your welfare, which cannot end but with my life, and the apprehension of danger natural to that solicitude, urge me on an occasion like the present to offer to your solemn contemplation, and to recommend to your frequent review, some sentiments which are the result of much reflection, of no inconsiderable observation, and which appear to me all important to the permanency of your felicity as a people.”

In his sweeping rhetoric, he warned of political factionalism, geographic disunity, and the dangers of interfering in international disputes.

If the past is prologue, Washington’s words certainly foretold of struggles the nation would come up against.

The annual Senate reading of the address began in 1896, but it was first read in 1862, to commemorate Washington’s 130th birthday, according to the US Senate website. During the throes of the Civil War, both chambers of Congress, Supreme Court justices, military officers, and cabinet members came together to hear the address read by Senate Secretary John W. Forney. President Abraham Lincoln did not attend because his son Willie had died just two days prior.

The Senate read the address again in 1888 to celebrate the centennial of the Constitution’s ratification.

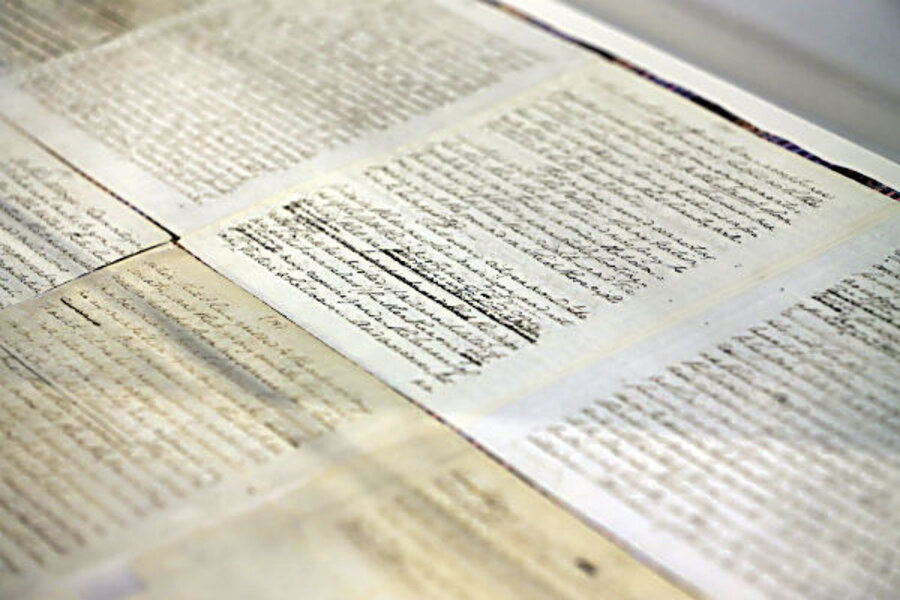

Starting in 1896, every senator who read the address (which takes roughly 45 minutes) signed their name and wrote comments in a leather-bound book kept by the secretary of the Senate.

The early remarks were mere formalities: “Read according to custom, pursuant to a resolution adopted by the Senate and by designation of the Vice President.”

But in the 1940s, comments became more personal, reflecting individual feelings or remarks about the politics of the day.

“Every citizen of the United States should consider it a duty to read Washington’s Farewell Address,” wrote Sen. Dennis Chavez (D) of New Mexico on Feb. 22, 1946.

In 1949, Sen. Margaret Smith (R) of Maine – the first woman elected to both houses of Congress and the first woman selected to read the address – speculated on how Washington would react to the formation of NATO, seeing as how he advised the US to take an isolationist approach to foreign policy.

“As I read this I wondered what our first President would think if he were alive today,” she wrote on Feb. 22, 1949. “Would he condemn the prepared North Atlantic Pact as an entangling alliance? The objective is the same today – freedom. The only difference is the way to obtain that freedom.”

Sen. Barry Goldwater (R) of Arizona, before his presidential aspirations, reflected on the looming Cold War and the threat of nuclear power.

“In these days, when troubles of the mind and the conscience are multiplying, as we tend to turn more to the material and less to the spiritual for the solutions to them, it is correct that Americans pause to remember their basic sources of strength – these sources are carefully outlined in the documents left to us by these wise men who, thru God, created our republic,” he wrote on Feb. 22, 1957.

In the aftermath of Sept. 11, 2001, Sen. Jon Corzine (D) of New Jersey said that Washington’s lessons were “for the ages.”

“At this time when our nation and her people have suffered, we must remember that our freedoms are not free,” he wrote on Feb. 25, 2002. “Like Washington and his fellow citizens, we must work for this freedom, and sadly, some will die defending them. Most importantly, we must stay united in the pursuit of freedom.”

What inspiration will the 113th Congress garner from Washington’s farewell address?

That might depend on who shows up to listen to the “sagacious words,” as Sen. Floyd Bentsen Texas called them in 1972.

The tradition has become mostly a formality. During last year’s reading by Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D) of New Hampshire, hardly anyone showed up to listen. Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D) of Connecticut listened from the dais, acting as Senate president pro tempore, while about 20 pages fidgeted in their chairs.

After the Senate comes back from recess on Feb. 25, Sen. Kelly Ayotte (R) of New Hampshire will deliver the address – the first time women have consecutively delivered the address.

In the age of partisan gridlock, Washington’s warnings of party extremism as a “spirit not to be encouraged” still ring true:

“And there being constant danger of excess, the effort ought to be by force of public opinion to mitigate and assuage it. A fire not to be quenched, it demands a uniform vigilance to prevent its bursting into a flame, lest instead of warming it should consume.”