A global warming summit of good intentions

Loading...

Tuesday's UN summit on global warming ended with assertions from United Nations officials and several heads of state that the meeting injected fresh political momentum into negotiations for a new global-warming treaty, which begin in earnest in less than three months.

But the road to some form of agreement in Copenhagen, Denmark, this December remains boulder-strewn.

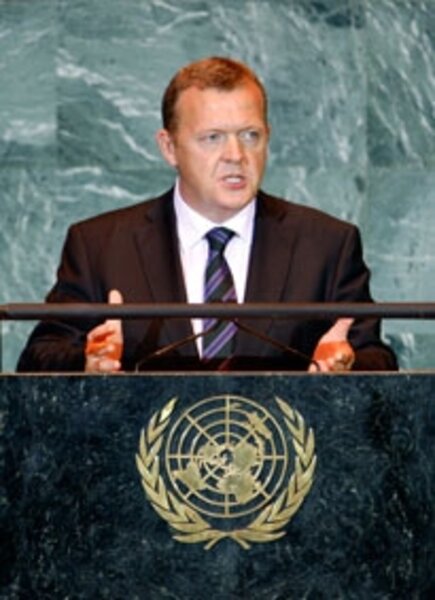

Noting that Tuesday's meeting was "a step in the right direction," Danish Prime Minister Lars Loekke Rasmussen added that "we're still far from a solution" to several vexing issues, including questions of how to help poor countries pay for the green technologies they will need to raise their standards of living without pouring more heat-trapping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

Still, after Tuesday morning's speeches and the afternoon's closed-door sessions, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said during a post-summit press conference that he noted "a thaw in several frozen positions."

For instance, Japan's new Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama told some 100 heads of state gathered for the meeting that his country would agree to reduce its greenhouse-gas emissions by 25 percent below 1990 levels by 2020, as long as there is "agreement on ambitious targets by all the major economies." His predecessor had proposed only an 8 percent cut below 1990 levels.

China announced its intention to cut the amount of carbon dioxide it emits for each unit of gross domestic product during its next five-year planning period, which begins in 2011. But it gave no number.

That came as no surprise to some, because that figure represents a bargaining chip for the Asian giant. But several long-time observers of the UN climate-talk process agree that for China to make the statement it did on such a high-profile international stage is significant.

"It's the first time China has committed to putting numbers on the table for reducing its carbon intensity," says Alden Meyer with the Union of Concerned Scientists in Washington.

But questions remain about the confidence in China's numbers. In its current five-year plan, China set a goal of reducing its energy intensity by 20 percent and is making progress along that path, several analysts have noted. Yet with little more than a year left, the country has achieved only a 7.4 percent reduction, according to an analysis by Roger Pielke Jr., a science-policy specialist at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

During a presummit briefing, Yvo de Boer, executive-secretary for the UN's Framework Convention on Climate Change, noted that negotiators in Copenhagen need to reach a political agreement on the major pieces of a new deal. These pieces include what he describes as "ambitious, legally binding emissions-reduction targets for industrial countries," clear indications that developing countries are taking steps beyond any they've already set in place to put them on a path that reduces their emissions below business as usual, financing for developing countries, and a governing structure that gives developing countries a greater voice in how that money is distributed and spent.

With a political agreement in hand, he said, negotiators can work out the details later.

But the glacial pace of negotiations over the past two years, plus the challenge President Obama and Democrats in Congress are having moving a major energy and climate bill through the US Senate, raises the prospect that negotiators may not deliver nearly as much as delegates envisioned when, in 2007 in Bali, they set up the road map for the current series of talks.

It's unclear how quickly details can be worked out after a political agreement is reached. The Kyoto Protocol was hammered out in 1997. Negotiators were still haggling over the details four years later.

Some are suggesting that negotiators need a fall-back scheme in their back pockets if Copenhagen talks end without an agreement.

For instance, political scientist David Victor at the University of California, San Diego has suggested reviving an approach, first offered up in the 1990s, in which countries would pledge action, then have a international body provide the reality check. If such an approach covered the highest emitters, he argues in a recent commentary published in the journal Nature, it could prove effective.

----

Obama 'determined to act' on global warming

The president told the UN Tuesday that the US is ready to join other developed countries in cutting emissions.

----Follow us on Twitter.