Who advises candidates on economic crisis?

Loading...

Barack Obama can boast that he has an eminent former Federal Reserve chairman on speed-dial, no less than the man credited with dousing the flames of 1970s stagflation.

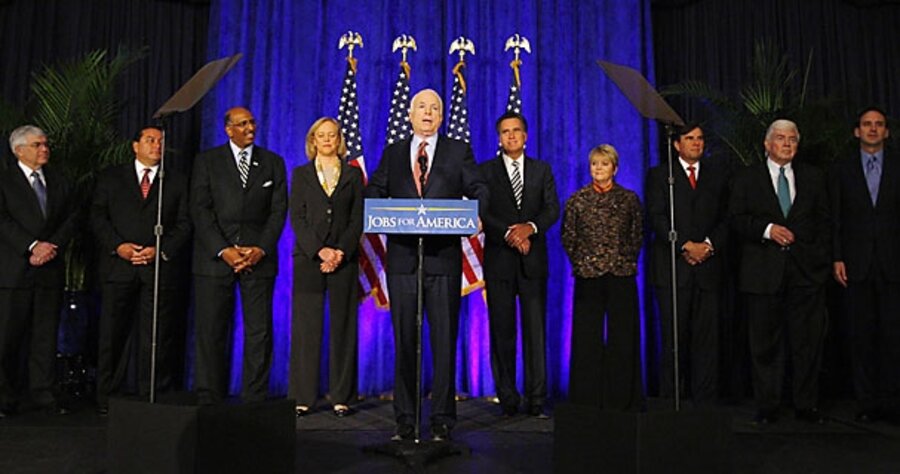

John McCain can point to a worldly-wise finance expert – one whose name is synonymous with an interest-rate formula that helps guide central bankers – at his side.

They are among the key advisers poised to serve as guiding lights to whichever candidate wins the election next Tuesday.

Economic advisers are perennially important to presidential policymaking, but rarely more so than now. Neither candidate has a background in economic policymaking, and the worst US financial crisis since the 1930s has evolved into a global storm.

On Thursday, the challenge was confirmed in a government report that America’s gross domestic product shrank in the third quarter at a 0.3 percent annual rate. More ominously, consumer spending took an unusually sharp dive, even for a recession.

When it comes to building a postcrisis foundation for jobs and growth, any new president will be expected to preside over a significant bolstering and rethinking of financial regulation.

But economists say that Senator McCain and his core economic aides would tilt toward fewer government prescriptions and less government spending.

Senator Obama and his team, by contrast, argue that America’s free-market economy will thrive best with a more visible government hand and with more policies aimed at people with modest incomes – what Obama calls a “bottom up” approach to growth.

A more immediate post-election task, however, is one in which many financial experts expect policy to be driven less by ideology than by financial-market exigency: trying to control the still-unfolding crisis in credit markets. In recent weeks, this has proved to be a daunting task.

“Both campaigns have moved to bring in more experienced hands,” says John Silvia, chief economist at Wachovia Corp. in Charlotte, N.C. “You need to call in people who have … some gray on their temples.”

The roster of advisers for Obama includes former Treasury secretaries from the Clinton administration: Robert Rubin and Lawrence Summers.

In the final presidential debate earlier this month, the Illinois senator also emphasized his ties with a billionaire investment whiz from Nebraska and the man who jacked up Federal Reserve interest rates two decades ago to end 1970s inflation. “Let me tell you who I associate with,” Obama said. “On economic policy, I associate with Warren Buffett and former Fed Chairman Paul Volcker.”

McCain has tapped into the wisdom of people such as John Thain, the head of Merrill Lynch, and John Taylor, a Stanford University economist who developed the influential “Taylor rule” for setting central-bank interest rates at an appropriate level. In the early years of Mr. Bush’s presidency, he also served as undersecretary of Treasury for international affairs.

Such picks are designed both to reassure the voting public and to seek answers to a crisis that has defied solutions for more than a year, says Mr. Silvia, who is on the roster of economists who openly support McCain.

Teams share similarities

“The big difference between the groups [counseling McCain and Obama] is probably not what they do this week or next week,” says Timothy Taylor, managing editor of the Journal of Economic Perspectives (no relation to John Taylor at Stanford).

He says either team is likely to focus on a quest already under way – using federal resources to help the banking system purge bad loans and rebuild reserves to revive normal lending.

“The big difference kicks in a year down the road when we confront the question of how are we going to reform our banking regulations to make sure that this doesn’t happen again,” says Mr. Taylor, the managing editor, who is not advising a campaign.

He says the Republican advisers lean toward mandating more transparency and disclosure by financial firms, “but not necessarily a lot of rules.”

The Democratic advisers, by contrast, are prone to impose tighter limits on the risks that financial firms can take.

The contrast may be one of degree. “Both [candidates] have chosen smart mainstream people” for counsel, Taylor says.

In fact, the two policy teams have some significant similarities. Both include seasoned thinkers from universities or business.

Yet both also rely on young policy experts who are inclined toward the ideological center, and well versed in the ways of Washington despite their relative youth. In the McCain camp, the economic policy portfolio has rested heavily with Doug Holtz-Eakin, who was known as a nonpartisan straight shooter in making fiscal forecasts as head of the Congressional Budget Office.

Obama’s answer to Mr. Holtz-Eakin is Jason Furman, who worked under President Clinton. In recent years, he roiled some liberals by writing a positive assessment of Wal-Mart’s impact on the US economy.

Austan Goolsbee, a University of Chicago economist who has advised Obama from the earliest days of his campaign, also has a centrist orientation.

“If I had to describe [Obama’s] approach to economics, I’d say pragmatic balance,” says Jared Bernstein, who has been consulted by Obama and who works at the liberal Economic Policy Institute in Washington. “He surrounds himself with many different views,” including those of some Republicans such as former Bush Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill, he says. “My view is that he cherry-picks the very best ideas.”

In discussions about economic growth and income inequality, he says, Obama will want to make progress on both fronts, not one or the other.

Similarly, McCain adviser John Taylor says in an e-mail interview that the Republican candidate actively solicits advice from a range of advisers.

McCain consults prominent academics, such as Harvard University’s Martin Feldstein and Kenneth Rogoff, and business leaders such as eBay’s Meg Whitman.

Different views on regulation

Taylor says the overall philosophy of McCain and his team contrasts sharply with Obama’s on several fronts, most notably taxes. He says Obama’s plan to boost taxes on upper-income Americans, including many job-creating small businesses, is “the exact opposite of a stimulus” for the ailing economy.

One close McCain adviser who has stirred particular controversy is Phil Gramm, a former senator from Texas. A long-time McCain associate, he lost his campaign co-chair role recently after he called America a “nation of whiners” and in a “mental recession.”

“In my view Phil Gramm is largely responsible for this whole mess,” since he was a key proponent of financial deregulation in the 1990s, says Lawrence Mitchell, author of “The Speculation Economy.”

The problem embodied in the thinking of Mr. Gramm and others such as the Fed’s Alan Greenspan, he says, was an ideologically driven view that markets can function without regulation. He worries that such views will persist in a McCain White House.

Obama’s team includes many people who served under President Clinton and signed those very deregulation efforts. But in Mitchell’s view, these advisers do not view regulation through the same lens as Gramm.

Keith Poole, a political scientist at the University of California, San Diego, notes the choice of advisers or campaign positions only goes so far in predicting what the next president will do. And whoever wins, he says, is “going to run into very rough water.”