Peace through strength? US rattles China with new defenses near Taiwan.

Loading...

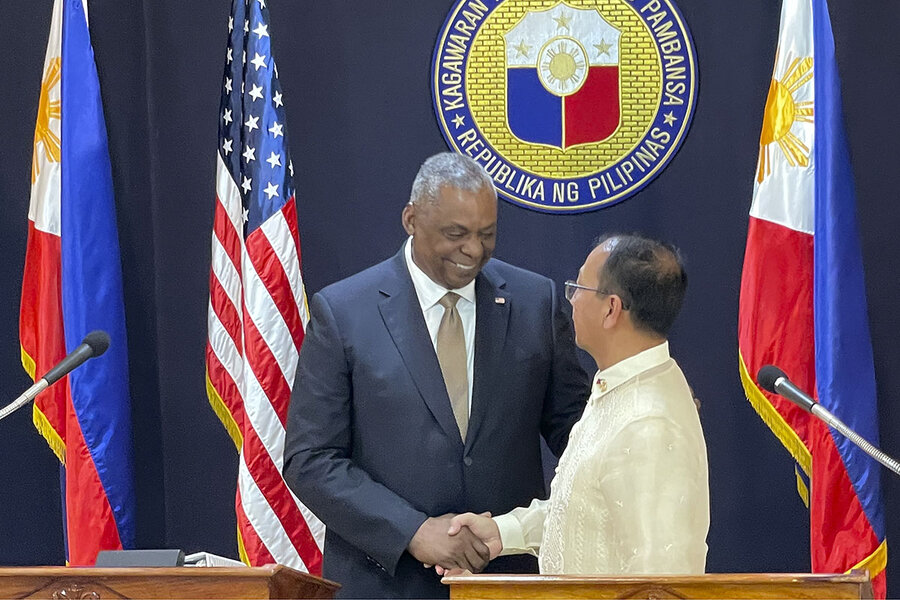

Pentagon officials last week announced an increase in the U.S. military’s footprint in Asia, with more troops headed to the Philippines.

The move is widely viewed as an effort to contain Chinese aggression in the region by projecting U.S. power. It will better allow U.S. forces to launch operations in the event of a crisis in Taiwan or the South China Sea.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onThe announced return of U.S. military forces to the Philippines comes at a time of rising U.S.-China tensions. A key question is whether this will escalate the rivalry or send signals that reduce the chances of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan.

Yet as Beijing ramps up its saber-rattling toward Taiwan, the move also has raised questions about how best to manage the risk of superpower conflict in the region.

Chinese officials said the move “escalates tensions.” And despite a military buildup by Beijing, some experts say China’s forces aren’t yet a match for America’s.

China’s two aircraft carriers, in particular, are frequently invoked as a sign of the ascendance of the country’s military might, since it’s often assumed they are roughly equivalent to their U.S. counterparts, notes Mike Sweeney, a fellow at the Defense Priorities think tank in Washington.

They’re not. The carriers aren’t nuclear-powered, nor do they have steam catapult technology, which is what allows U.S. fighter jets to fly, slingshot-style, off the deck.

The People’s Liberation Army is “not 20-feet tall,” says Mr. Sweeney, “but they’re not 4-feet tall, either.”

When an American four-star general warned his commanders in a leaked letter last month that, while he hoped he was wrong, his “gut” told him the United States will be at war with China in a couple of years, Pentagon officials publicly insisted the comments do not represent their view of the matter.

That said, they also announced an increase in the U.S. military’s footprint in Asia last week, with more troops headed to the Philippines as part of a new basing agreement – a handy setup should Beijing, say, try to invade Taiwan.

Chinese officials called the move “selfish,” adding that it “endangers regional peace” and “escalates tensions.” From the Pentagon’s perspective – particularly on the heels of scrambling to shoot down a suspected spy balloon loitering over U.S. nuclear silos – that’s Beijing’s forte.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onThe announced return of U.S. military forces to the Philippines comes at a time of rising U.S.-China tensions. A key question is whether this will escalate the rivalry or send signals that reduce the chances of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan.

Stationing some U.S. forces at Philippine military bases, about three decades after large American bases there closed, is widely viewed as an effort to contain Chinese aggression in the region by projecting U.S. power. It will better allow U.S. forces to launch operations in the event of a crisis in Taiwan or the South China Sea.

Yet as Beijing ramps up its saber rattling toward Taiwan, the move has raised questions about how best to manage the risk of superpower conflict in the region.

While it’s not hard to see why the new announcement on bases seems hostile to Beijing, “we’re not talking about putting intermediate-range ballistic missiles there, which would look like an ability to attack targets in China,” says Eugene Gholz, associate professor of political science at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana.

Should China become an implacable aggressor, however, the Pentagon does have war plans in place to attack China’s defensive bubble. The current U.S. footprint in the region fishhooks from Japan through Guam to the coming presence in the Philippines, creating the capability to launch airstrikes to destroy thousands of communications systems, missile launchers, and radars. As China’s military isn’t currently built for power projection, Beijing could easily interpret these plans as U.S. intent to destroy China’s defenses in a first strike.

This all creates a “spiral of hostility” that has the potential to create a “downright dangerous, use-it-or-lose-it” situation when it comes to Beijing’s nuclear arsenal, Dr. Gholz says.

Should they fear a U.S. first strike, Chinese leaders may decide to launch one of their own while they still have control of their weapons, he notes.

For this reason, analysts say, China is ramping up its production of nuclear warheads. It now has more intercontinental ballistic missile launchers than the U.S., according to a U.S. military report to Congress released this week, prompting Republican leaders to call for “higher numbers and new capabilities” in the U.S. nuclear arsenal.

Still, the Biden administration has largely continued the tough stance that the Trump administration took before it, approving Pentagon moves that have been called everything from a cynical play for more defense dollars to smart power projection in a bid to curb Beijing’s aggression.

The question, analysts say, is what might these moves achieve, and whether there is a way forward that combines strategic restraint with cleareyed realism in an effort to temper the dangerous and often outrageous expense of escalation.

Chinese self-assessments

High up on the list of Pentagon concerns is that although China advocates for peaceful unification with Taiwan, it has never renounced the use of military force despite clear indications that invasion would come with an enormous price.

President Joe Biden has pledged that U.S. forces would defend Taiwan in the event of a Chinese invasion. A war game conducted last year by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) concluded that the U.S. would win, but with losses that “would damage the U.S. global position for many years.” China would fare worse, with its navy “in shambles” and tens of thousands of troops taken prisoners of war.

The question, analysts say, is whether China takes these sorts of lessons to heart. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, after all, has shown that leaders can have an outsize view of what their militaries can easily accomplish.

“I have a lot of concerns about the Chinese military, but the big question is, what do the Chinese think about their prospects themselves?” says Mike Sweeney, a fellow at the Defense Priorities think tank in Washington who has served as rapporteur for the Pentagon’s Defense Policy Board.

“This notion that the Russians believed the Ukraine war would be over in weeks – do the Chinese have the same delusions about Taiwan? Does the PLA [People’s Liberation Army] have the gumption to go to senior leadership and say how difficult this is?” he adds.

It is a concern shared by top U.S. officials as well. “If the political leadership turned to the [PLA] today and said, ‘Can you invade right now?’ it’s my assessment that the answer would be a firm yes,” Lonnie Henley, a former intelligence officer for the Defense Intelligence Agency, said in a 2021 congressional hearing.

But, as with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it would not occur without warning. While Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley said that he “did not dismiss at all” that the PLA has a goal of developing the capability to invade Taiwan by 2027, he added, “I don’t see it happening right out of the blue.”

Geography constraints

That’s in large part because the basic facts of geography naturally constrain Beijing’s potential efforts to project power.

Its ships and submarines must sail through relatively shallow waters and distinct choke points to reach the broader Pacific, which means that even East Asian nations “with extremely limited military capabilities” can create highly effective defensive networks with anti-access weaponry like missiles and mines, backed up by sophisticated networks of sensors, Dr. Gholz says.

Given these constraints, the Pentagon has been charged with threat inflation for its tendency to, as Dr. Gholz puts it, “equate security with total military dominance.”

Accustomed to being the premier naval presence in the Pacific, “U.S. defense planners tend to see any diminution of military advantage as a disaster” – including China’s heightened ability to defend itself against the U.S., he adds.

China’s military capabilities

To this end, it’s helpful to soberly assess the capabilities of China’s military, analysts say – including its status, for example, as home to the world’s largest navy, which might seem reasonably alarming at first glance.

“But you don’t even have to scratch the surface very much before you realize, ‘Wait a minute – China isn’t building a military to invade the West Coast of the U.S. They’re building a military to keep us out of China,’” says Dan Grazier, senior defense policy fellow at the Project on Government Oversight (POGO) and a former Marine Corps captain.

What the U.S. fleet lacks in total numbers it makes up for in tonnage, which is more than double that of China’s ships, he points out in a POGO analysis published in December. This means that the Pentagon’s ships are literal heavyweights, able to make longer voyages, carry more fuel and munitions, and project power in a way that Chinese vessels simply cannot.

China’s two aircraft carriers, in particular, are frequently invoked as a sign of the ascendance of its military might, since it’s often assumed they are roughly equivalent to their U.S. counterparts, Mr. Sweeney says.

They’re not. The carriers aren’t nuclear-powered, nor do they have steam catapult technology, which is what allows U.S. fighter jets to fly, slingshot-style, off the deck. Based on a 40-year-old Soviet design, China’s carriers instead have curved, ski-jump fronts.

These two traits are important: Without nuclear power, carriers are limited in their range, and without catapults, the aircraft on board are limited in the amount of fuel and ordnance they can carry.

So while “it would be wrong to call China’s aircraft carriers mere status symbols without any combat function at all,” Beijing is “more likely to deploy their fighters in an air defense role rather than strike deep into an opponent’s territory,” Mr. Sweeney writes in a 2020 Defense Priorities analysis.

Beneath the surface, the Chinese submarine force is about the size of America’s, but only six of its 66 submarines are nuclear-powered. All of the U.S. Navy’s subs are nuclear-powered, which, among other things, gives them far greater range.

Chinese submarines also make a lot of noise compared with the U.S. fleet, which makes them easier to detect with the Pentagon’s substantial network of undersea sensors.

At the lower-tech end of the spectrum, it is “baffling” – but encouraging – to many military analysts that China “simply has not built enough basic transport ships to ferry a sufficient number of troops” to Taiwan should it decide to invade its shores, he adds. “The math simply does not work.”

Constructive engagement

That is not to say that there haven’t been troubling developments. In the CSIS war game, China simply commandeered commercial vessels to ferry its troops when it decided to invade Taiwan.

China is also building a third aircraft carrier that promises to be “much larger” than the first two and what analysts call “decent destroyer ships” to escort their carriers.

At the same time, the PLA has increased provocative actions in and near the Taiwan Strait.

“The PLA’s not 20-feet tall, but they’re not 4-feet tall, either,” Mr. Sweeney says.

Though nuclear uncertainties, coupled with China’s gray-zone activities and “ham-fisted bullying” of its neighbors, tend to discourage constructive engagement, the two nations should continue to work toward engagement anyway, Mr. Sweeney says.

This could include military-to-military exchanges and other confidence-building measures that could “create a pathway for deescalating a crisis if one begins,” Mr. Sweeney says. “I’d still very much like us to have perspective – and for us not to go too far down the road into unnecessary confrontation.”

Conflict with China, he adds, need not be a foregone conclusion.

Editor's note: The description of Mike Sweeney has been corrected in regard to his role (as the rapporteur) with the Pentagon’s Defense Policy Board.