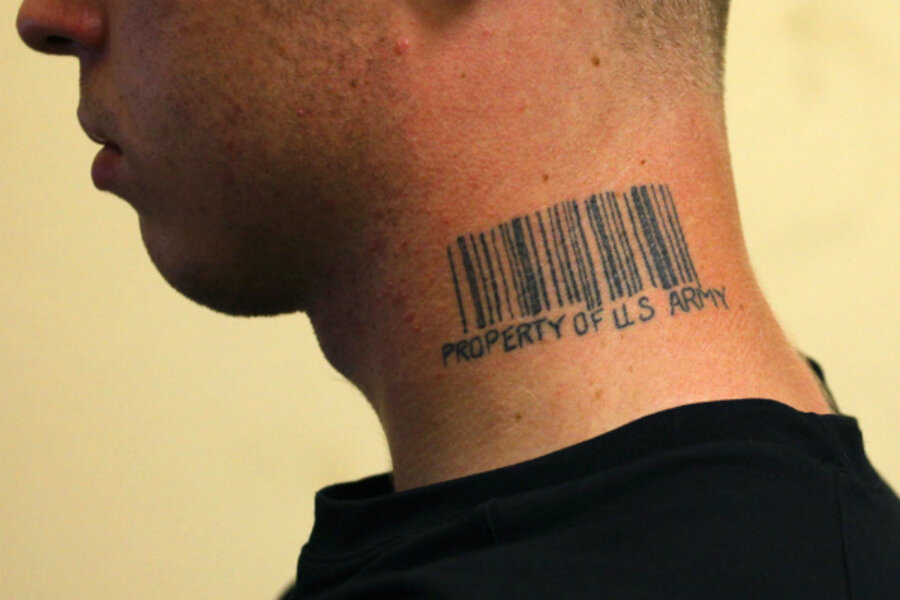

New Pentagon rules ban tattoos on the neck and below elbows or knees

Loading...

| WASHINGTON

For new US military recruits, there are new body art rules on the horizon that boil down to no neck tattoos and no ink below the elbows or knees.

The regulations are expected to take effect in the next month or two.

In the midst of two wars in Iraq and Afghanistan – when the Pentagon was in desperate need of recruits – the military looked the other way when it came to tattoos, as long as they were not deemed racist, sexist, or extremist.

With the military under pressure to dramatically cut its ranks in the face of growing fiscal constraints, the Pentagon can afford to be pickier about the troops it chooses to bring into the force.

In a meeting with US soldiers in Afghanistan this week, the Army’s top enlisted officer, Sgt. Maj. Raymond Chandler, told them that the point of the new regulations is to maintain a uniform look and to sacrifice for the sake of the force, according to Stars & Stripes.

“When a soldier gets a tattoo that contains a curse word on the side of his neck, I question, ‘Why there? Are you trying to stand out?' ” Chandler told the soldiers, according to Stars & Stripes.

The soldiers will be responsible for paying for the removal of any tattoos that violate the new regulations.

As they stand now, the new rules “are kind of obvious,” says C.W. Eldridge, a US Navy veteran and owner of the Tattoo Archive, a working shop and a nonprofit that specializes in tattoo history in Winston-Salem, N.C.

Mr. Eldridge calls these parts of the body “public skin.”

“A lot of people who come in and want their hands tattooed or a crazy pit bull on their neck – I just know that somewhere down the road it’s going to get in their way,” he says. “That’s why I won’t do them.”

After four years of service in the 1960s, Eldridge became a tattoo artist in San Francisco, home at the time to several military bases, where he tattooed sailors from visiting fleets every day.

They considered tattoos part of a rich military tradition, he says. “Sailors aboard ships didn’t have any room to store a cool carving or a statue, so they collected their souvenirs on their bodies.”

Sailors got the popular anchors and knots, but occasionally hand tattoos as well.

One popular pick was a knuckle tattoo that read “hold” on one hand and “fast” on the other. For sailors, not an unsuperstitious lot at the time, “The theory was that when you were climbing in the riggings, your hands would ‘hold fast’ and you wouldn’t fall.”

During the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, many US troops have collected tattoos that have become personally meaningful to them, “kind of like mile markers in their lives,” Eldridge says.

“It’s almost encoded – it’s an iconic image for another military person, a whole group identity thing,” he adds, noting that many often opt for the logos of their military unit. “As soon as they see it, they know something about that person. They have not only the memory of the war, but the actual mark of that period.”