‘Record speed and focus’: Biden’s judicial picks diversify bench

Loading...

In four years, President Donald Trump made more than 200 judicial appointments, and they were mostly white men. The figures are striking – 84% were white and 76% were male – as was the speed of appointments.

Last year, President Joe Biden followed suit – in one regard.

Why We Wrote This

Like his predecessor, President Joe Biden is focused on getting federal judges confirmed, and he’s been quite successful at it his first year in office. But the comparison stops with numbers.

No president since Ronald Reagan has gotten so many judges confirmed in his first year. But Mr. Biden has also fulfilled a campaign promise by nominating perhaps the most diverse slate of judicial picks ever: 75% are women and 71% are people of color.

Where the Biden administration has really been breaking new ground, though, is in the professional diversity of its judicial picks.

Traditionally, federal judges have worked as federal prosecutors or in big law firms. But only a quarter of President Biden’s judges ever worked as prosecutors, and about half had careers in public defense or advocacy. People who have represented indigent defendants or who have fought the government or big corporations in court bring valuable perspectives to the bench, experts say. And as federal judges, they have tenure for life.

These judges “are going to be there for 30 or 40 years,” says Christina Boyd, an associate professor at the University of Georgia. “This is going to be a long stamp on federal law and policy.”

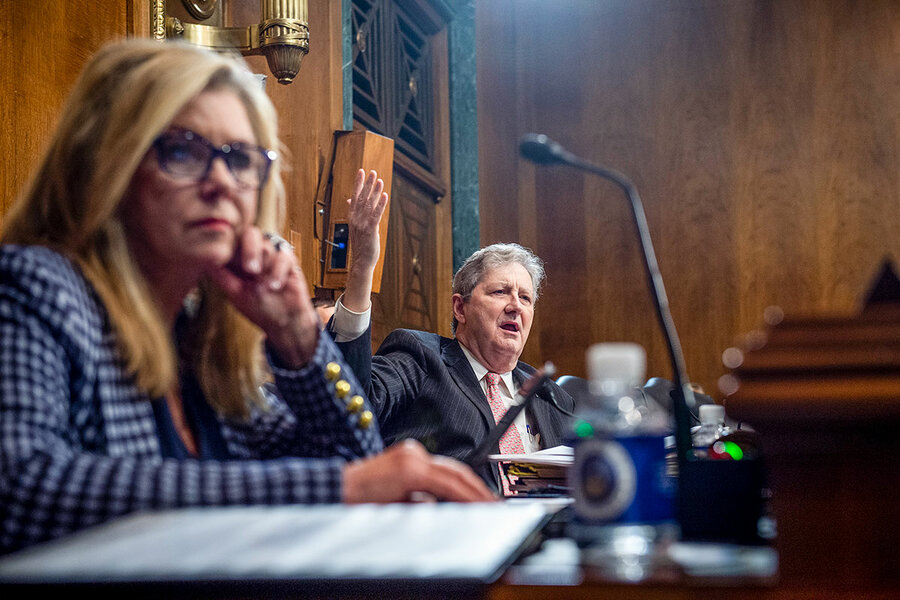

During a hearing on her nomination to the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, Jennifer Sung hit a speed bump.

Republican Sen. John Kennedy from Louisiana, one of the Senate Judiciary Committee’s more acerbic questioners, had taken issue with a letter Ms. Sung co-signed in 2018 describing U.S. Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh as “morally bankrupt.”

An Oregon labor lawyer who would be the first Asian American and Pacific Islander to serve on the 9th Circuit in Oregon defended the letter but said that if confirmed, “I would absolutely respect the authority of every Supreme Court justice, and all of its precedents, without reservation.”

Why We Wrote This

Like his predecessor, President Joe Biden is focused on getting federal judges confirmed, and he’s been quite successful at it his first year in office. But the comparison stops with numbers.

“See, I don’t believe you,” replied Senator Kennedy. “I think you said a few years ago what you said about Brett Kavanaugh, and I think you believed it.”

Three months later, on Dec. 15, 2021, in a 50-49 party-line vote, the Senate confirmed her, along with another federal district court nominee. Later that week the Senate voted to confirm nine more district court judges, bringing President Joe Biden’s number of judicial appointments to 40.

Quietly, this has been one of President Biden’s most impressive achievements in his first year in office. No president since Ronald Reagan has gotten so many judges confirmed in his first year. Mr. Biden has also fulfilled a campaign promise by nominating perhaps the most diverse slate of judicial picks ever: 75% are women and 71% are people of color, according to FiveThirtyEight. Also important, court watchers say, is that the 40 new judges bring with them a wide backdrop of legal experience. Rather than prosecutors and Ivy League professors, these are public defenders, civil rights lawyers, and, as in the case of new 9th Circuit Judge Sung, labor rights lawyers.

In a year in which pandemic recovery, voting rights, and other legislative priorities have languished, Senate Democrats and the Biden administration have been ruthlessly efficient in trying to stock the federal judiciary with progressive judges likely to serve for decades.

Their blueprint for this finely tuned confirmation machine? The Republican Party, and in particular, the Trump administration.

“Modern presidents take appointing federal judges very seriously,” says Christina Boyd, an associate professor of political science at the University of Georgia. “But we’re seeing record speed and focus from the Biden administration on their federal judgeships in ways we probably haven’t seen, especially for a Democratic administration, maybe ever.”

“There definitely has been some learning”

President Biden may also have been facing unprecedented pressure from his base to focus on judicial appointments.

In four years, President Donald Trump made more than 200 judicial appointments, including three Supreme Court justices and 54 appeals court judges – and they were mostly white men. The figures are striking – 84% were white and 76% were male – as was the speed of appointments. By the time President Biden was inaugurated on Jan. 20, 2021, some 28% of active federal judges had been appointed by President Trump. That compares with 17% for President Barack Obama after his first term.

Watching the contentious confirmations of Justices Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett – the latter just a month before the presidential election – “outraged” progressives, says Daniel Goldberg, legal director at the Alliance for Justice, which advocates for progressive judicial appointments.

“A galvanized public demanded that this president and the Senate prioritize putting on the bench judges who will protect the rights of all Americans, not just the wealthy and powerful,” he adds.

For both parties, appointing judges has become an important issue for base voters. Partisanship and gridlock, at least on major legislation, have taken a stronger hold in Congress, and the White House and the courts have become more active in driving policy changes – particularly when the presidency and Congress are divided.

And in the three branches of government, federal judges are the only members with life tenure.

“Once you get judges on the bench, they’re shaping law for decades,” says Gbemende Johnson, an associate professor at Hamilton College in Clinton, New York, who studies judicial politics.

“As you see greater polarization, that has only added to the battles over these seats,” she adds.

President Biden, a former vice president and chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a veteran of those political battles. That experience has helped his administration build an efficient system for processing and confirming judges, but he would also have been aware of the criticism President Obama received over the low priority his administration gave to judicial appointments.

The speed with which President Trump was able to appoint judges “caused a lot of alarm for Democratic supporters,” says Dr. Johnson. “There definitely has been some learning.”

The Trump administration had a team within the White House Counsel’s office focused on judicial nominations. They also worked closely with the conservative Federalist Society and senior Senate Republicans like Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and Judiciary Committee Chairmen Chuck Grassley and Lindsey Graham.

Former President Trump and senior Senate Republicans “set up one of the most efficient assembly lines ever for judicial nominees,” says Mike Davis, a former aide to Senator Grassley and founder of the Article III Project, a group formed during the Trump administration to promote conservative judicial picks.

“President Biden is now benefiting from that,” he adds.

Noting specifically the hiring of Ron Klain as chief of staff and Paige Herwig, a former Democratic staffer on the Senate Judiciary Committee, to the White House Counsel’s office, he says, the Biden administration “has assembled a very competent and experienced team to very quickly fill these judicial nominations.”

“I think Ron and Paige understood Democrats did a very poor job of filling judicial vacancies in the past,” says Mr. Davis.

A focus on experiential diversity

The Biden administration has not just been getting federal judges confirmed at a breakneck pace. The confirmations also represent a historically diverse slate of judges.

The percentages of women and people of color appointed are higher than for any president in history, but where the Biden administration has really been breaking new ground is in the professional diversity of its judicial picks.

Traditionally, federal judges have often come from careers as federal prosecutors or lawyers in big law firms. But only a quarter of President Biden’s judges ever worked as prosecutors, and about half had careers in public defense or advocacy, according to FiveThirtyEight.

“This is probably the first time we’ve seen a presidential administration actively focus on getting more experiential diversity on the federal courts,” says Dr. Boyd of the University of Georgia.

People who have represented indigent defendants or who have fought the government or big corporations in court bring valuable perspectives and experiences to the bench, experts say. A former public defender may have a better understanding of ineffective assistance of counsel claims (which argue that poor defense representation probably affected the decision); an environmental lawyer may have a better understanding of the harms industrial activity can have on people and wildlife.

“Just because you’re a prosecutor doesn’t mean you’re completely unsympathetic to those things,” says Dr. Johnson from Hamilton College. “But it’s in these other areas that [President Biden] is going to find nominees that are more likely to align with [his] policy and legal priorities.”

It’s unclear how professional diversity affects the outcome of actual cases, according to Dr. Boyd. But there has been extensive research on the practical effects of racial and gender diversity in the federal courts.

Studies have found that a trial judge’s sex and race have very large effects on their own decision-making and the decision-making of their colleagues. (In appeals courts, where judges often handle cases in panels of three, the latter effect can be particularly significant.) Women and nonwhite judges also write longer and more detailed opinions, according to a study last year.

“It might be just five out of 500 defendants see a different outcome,” says Dr. Boyd, “but I think the likelihood we get different outcomes will be there.”

There could be a looming challenge, however.

Most of the judicial vacancies still to be filled are in purple and red states. During the Trump administration, the Republican-led Senate Judiciary Committee did away with the “blue slip” tradition, which allowed state senators to weigh in on appeals court nominees in their home states. Current Senate Judiciary Chairman Richard Durbin, a Democrat from Illinois, has said he is not going to reinstate the courtesy. But as the midterm elections draw closer, Senate Republicans may fight harder to keep vacancies open, hoping to win back control of the chamber in November.

With the Supreme Court deciding only about 60 or 70 cases a year, appeals courts deliver the final verdict on most cases in federal courts. Former President Trump’s speed with regard to appellate judges helped him create Republican-appointed majorities on five of the 13 appeals courts and expand majorities on three. So far, President Biden has been able to shift the ideological majority on one appeals court – the 2nd Circuit – and he has the opportunity to flip the 3rd Circuit this year as well.

One certainty is that many people, on the right and the left, will be watching.

“We’re definitely getting a lot of attention on the judiciary these days,” says Dr. Boyd.

President Biden’s judges “are going to be there for 30 or 40 years. This is going to be a long stamp on federal law and policy,” she adds. “Senators are seeing that, and the public [is] seeing that.”