Vigilance or vigilantism? Old laws’ legacy in modern US.

Loading...

| Savannah, Ga.

Two high-profile murder trials coming to a close in the U.S. pose a challenging question: To what extent can a regular citizen legally take on the duties of an armed agent of the state?

On the shores of Lake Michigan, a jury is weighing evidence against a teenager who killed two people and wounded a third after bringing a military-grade rifle to a city gripped by social unrest.

Why We Wrote This

The Rittenhouse trial, the trial of Ahmaud Arbery’s killers, and Texas’ controversial abortion law all point to some Americans’ increasing desire to aggressively police others’ behavior. The trend has echoes of vigilantism’s long history in the U.S.

A thousand miles away, in Brunswick, Georgia, prosecutors have charged three white men with murder for chasing down, cornering, and then killing a Black jogger named Ahmaud Arbery. The men said they were trying to execute a citizen’s arrest. The man who fired his shotgun said he did it in self-defense after Mr. Arbery, who carried neither gun nor stolen goods, turned on his pursuers.

The trial dynamics have left Americans scrambling to unspool the implications of what Harvard historian Caroline Light calls a “tortured tangle of old and very new laws” that together are transforming the nature of protest and citizenship.

Citizen “enforcement of different or related social norms [is] the legacy ... that descends down to us today – and what you see in these trials,” says Robert Tsai, a law professor at Boston University.

Two high-profile murder trials coming to a close in the U.S. pose a challenging question: To what extent can a regular citizen legally take on the duties of an armed agent of the state?

On the shores of Lake Michigan, a jury is weighing evidence against a teenager who killed two people and wounded a third after bringing a military-grade rifle to a city gripped by social unrest.

A thousand miles away, in Brunswick, Georgia, prosecutors have charged three white men with murder for chasing down, cornering, and then killing a Black jogger named Ahmaud Arbery. The men said they were trying to execute a citizen’s arrest. The man who fired his shotgun said he did it in self-defense after Mr. Arbery, who carried neither gun nor stolen goods, turned on his pursuers.

Why We Wrote This

The Rittenhouse trial, the trial of Ahmaud Arbery’s killers, and Texas’ controversial abortion law all point to some Americans’ increasing desire to aggressively police others’ behavior. The trend has echoes of vigilantism’s long history in the U.S.

The trial dynamics have left Americans scrambling to unspool the implications of what Harvard historian Caroline Light calls a “tortured tangle of old and very new laws” that together are transforming the nature of protest and citizenship.

“These cases are mirror images of each other in terms of figuring out the landscape of firearms in society writ large,” says Seattle-area firearms instructor Brett Bass, a former military police officer.

Though the details are different, the two trials address in their own way the interplay of guns and power in a country where the sight of citizens brandishing weapons to enforce order or protect property has become increasingly common.

In some ways, in the midst of police reforms, constitutional carry, and liberalized self-defense laws, it’s a picture of a country reverting to a past norm: The 19th-century doctrine of Manifest Destiny held that the United States was divinely authorized to spread capitalism and democracy throughout the American continents. The result was war with Mexico and mass violence against Indigenous people, justified by self-defense claims of white settlers.

During its history, the U.S. has hosted hundreds of vigilante movements, including the Ku Klux Klan, that have operated with varying degrees of state blessing. Some literally got away with murder. Between 1882 and 1968, 4,743 people were lynched in the United States, according to Tuskegee University.

Citizen “enforcement of different or related social norms [is] the legacy ... that descends down to us today – and what you see in these trials,” says Robert Tsai, a law professor at Boston University.

A convergence of laws leading to tragedy

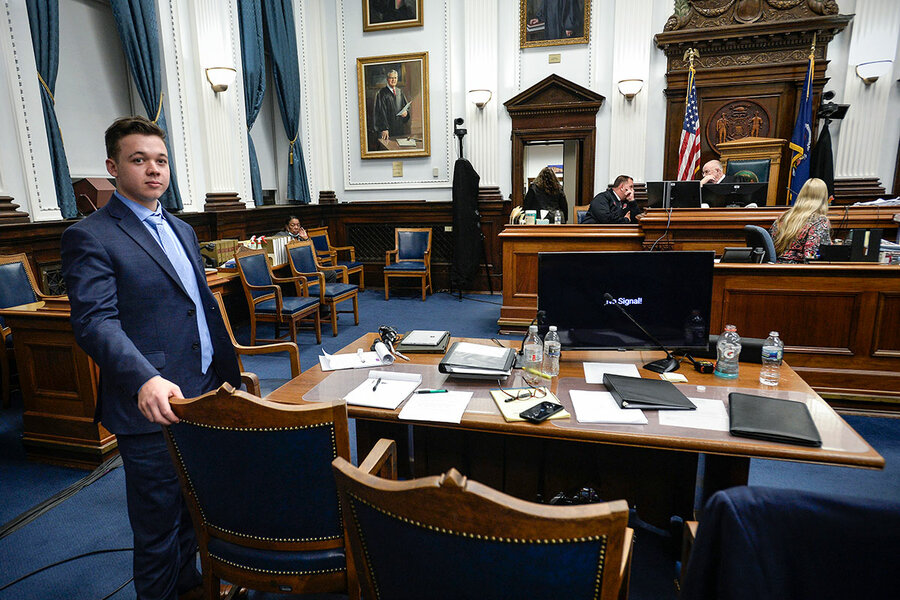

In Kenosha, Wisconsin, a mostly white jury is navigating a complex case. The law doesn’t protect people who start a fight and then claim they killed in self-defense. But the jury will ultimately decide whether Kyle Rittenhouse, who traveled from his home state, acted reasonably in the moment when he raised his barrel to shoot.

In Brunswick, prosecutors say “driveway decisions” and “assumptions” sparked the men – Greg McMichael, his son Travis McMichael, and neighbor William “Roddie” Bryan – to chase Mr. Arbery. The men weren’t arrested until a video showing the shooting appeared two months after the death, causing a national outcry.

All those involved in the Kenosha incident were white. But the racial component of the Brunswick case – in particular, its disturbing link to the state’s Jim Crow lynching legacy – gives experts added pause.

“What the Ahmaud Arbery murder reveals is the convergence of citizen’s arrest and stand your ground and open carry laws – it’s all those together,” says Joseph Margulies, a human rights expert at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Citizen’s arrest laws vary by state, but allow a person who witnesses a crime to detain the person committing it. Stand your ground laws, which came to national attention during George Zimmerman’s trial for killing Trayvon Martin, permit a person to use force, including deadly force, in a confrontation. Open carry laws, which are in a majority of states, allow gun owners to carry weapons openly in public.

“Citizen’s arrest gave [the defendants] the ostensible authority to act, open carry lets them hop into their truck with a gun, and ‘stand your ground’ lets them shoot when Ahmaud Arbery resists, because now they’re worried about the threat of bodily injury,” explains Mr. Margulies. “Add in a dash of implicit and explicit bias and, predictably, you’re going to have the murder of young Blacks who are doing nothing except jogging through the neighborhood.”

The three men’s attorney contends that laws that blur the line between citizen and state bolster the men’s defense, given that their intent was to protect their neighborhood.

“The why it happened is what this case is about,” defense attorney Franklin Hogue said last week. “This case is about intent, beliefs, knowledge – reasons for beliefs, whether they were true or not.”

In both incidents, defendants armed themselves in the name of protecting someone else’s property. But those actions had another purpose, experts say: They were attempts to establish a hierarchy, using armed force as a claim on state power.

“In both of these cases, we can see that the law ... has been carefully crafted to ensure that it looks neutral,” says Professor Light at Harvard. “But in its actual application it excuses violence under the guise of self-defense for powerful social actors.”

Citizens policing other citizens

The laws have emboldened at least some Americans to establish a more offensive posture toward other citizens, sometimes at the urging of the state. Take Texas. In a bid this year to ban abortion, state law now offers a $10,000 bounty to citizens to sue abortion providers. The Supreme Court is set to rule any day on whether that law is constitutional.

But progressives, too, have posited similar ideas in the wake of social justice protests after George Floyd’s murder in May 2020. The defund the police movement – as well as autonomous zones set up in Seattle, Atlanta, Minneapolis, and a few other cities – stems from the hypothesis that a shift of resources away from coercive policing would empower citizens to take a bolder role in dealing with neighborhood issues, including, ostensibly, petty crime.

“The interplay is thorny – that interplay between shifting responsibility away from police ... but then asking: To whom are you shifting it? And is that result a salutary one?” asks Mr. Margulies at Cornell. “What this vigilantism shows is that communities may not get this right, either.”

At least 560 demonstrations in the past few years have included citizens bringing firearms, purportedly to assist police in protecting property. Those gatherings were six times more likely to turn violent than unarmed gatherings, according to Everytown, a gun control advocacy group.

Last year, armed militiamen glared from the rotunda above Michigan lawmakers debating COVID-19 lockdowns. Some of those men later were arrested by the FBI on domestic terrorism charges for a plot to kidnap Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer. One man pleaded guilty and was sentenced to six years in prison. Attorneys for the others are arguing that the plot to kidnap an elected official was in essence a high-level citizen’s arrest justified by the pandemic’s blow to civil liberties.

Some Republican lawmakers have worked to portray the deadly violence of the Jan. 6 insurrection as the understandable outcome of allegations of a stolen election, despite the lack of evidence. Some 700 people have been arrested so far for their role in storming the Capitol. On Wednesday, the so-called Q Shaman, Jacob Chansley, was sentenced to three years and five months in prison – the longest sentence handed down to date.

“What we see percolating to the top of the cultural conversation is not the language of defense – it is the language of aggression,” writes Kimberly Kessler Ferzan, co-director of the Institute of Law & Philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania, in a recent paper. Using violence in the name of the state “is where the action is.”

Courts are clearly dealing with the ramifications of violence in the name of protecting others. But the issue is also coming to a head for elected officials.

After the killing of Mr. Arbery, Georgia quickly narrowed its citizen’s arrest law to allow only shopkeepers to detain suspected shoplifters. Gov. Brian Kemp, a Republican, said the old law could be “used to justify rogue vigilantism.”

Whether other states will follow suit is unclear. South Carolina’s citizen's arrest law suggests that citizens may use the cover of darkness to capture those they suspect of wrongdoing, even allowing them to kill their captives. It was written in the 1860s.

A bill to change that language died in committee this year.

Cynthia Lee, a professor at George Washington University School of Law, created a model use-of-force ordinance being adopted across the U.S. Professor Lee, author of “Murder and the Reasonable Man,” is working on legal language that would help lawmakers – and police – establish when brandishing a weapon poses a civil or constitutional threat.

For now, the trials in Brunswick and Kenosha, Mr. Bass believes, will at the very least serve as a cautionary reminder: The same weapons that are seen as symbols of liberty can put a person’s liberty at risk.

“It’s worth highlighting that, no matter the verdict, the system is still working,” says Mr. Bass, with defendants facing charges of murder in both instances.

State prosecution of both cases, he says, shows that “if your objective is not to get killed or have somebody you care about not get killed, you have to accept that the cost of surviving that encounter – or even saving someone’s life – could be very dire.”