‘Packing the court’ and partisan politics: Three questions

Loading...

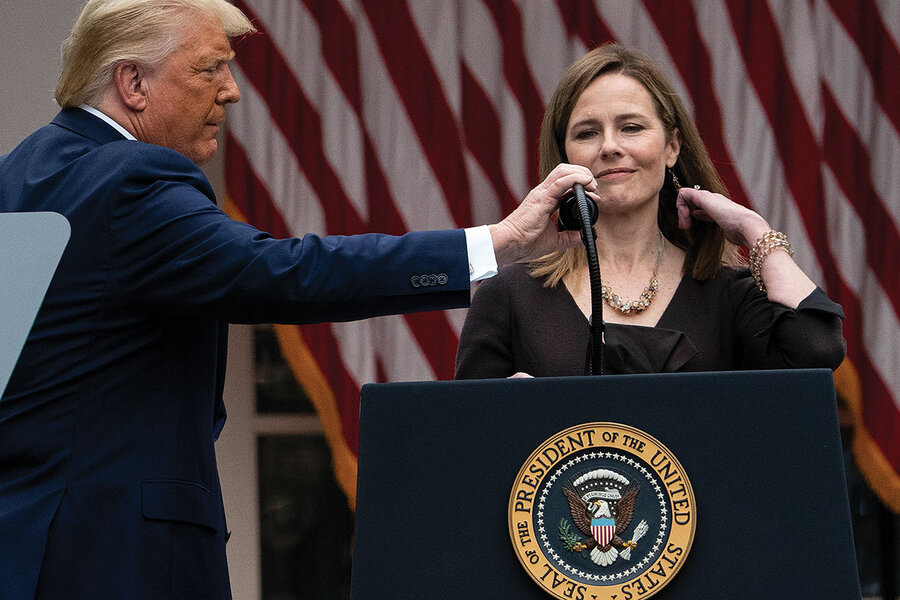

President Donald Trump’s nomination of Judge Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court of the United States has stirred a cyclone of frustration among congressional Democrats. Some lawmakers are considering trying to increase the number of seats on the high court. Such “court-packing” plans may be feasible but are highly controversial.

Politically, meddling with the Supreme Court’s size is a dangerous venture that could provoke what one legal scholar calls “an endless cycle of tit-for-tat court-packing.”

Why We Wrote This

Legal scholars caution that efforts to “pack the court” could launch a tit-for-tat fight over the least-political branch of the government. But there are other paths that would avoid blowing up the Supreme Court.

There are other options available. Politicians on both sides have suggested imposing an 18-year term limit on justices, so that two would be replaced every four-year presidential term, bringing predictability to the appointment process. But experts question whether such a reform would require a constitutional amendment.

Congress could also limit the Supreme Court’s influence by using an obscure constitutional ability to curtail the court’s jurisdiction – effectively letting Congress declare certain laws unreviewable by the high court.

And Adam Levitin, a professor of law at Georgetown University, has proposed expanding the court to 33 justices and randomly picking three-justice panels for each case. This plan, he says, offers a bipartisan path from the winner-take-all structure of today’s court and could help mollify the now-contentious nomination process.

President Donald Trump’s nomination of Judge Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court of the United States has stirred a cyclone of frustration among congressional Democrats. Threatening recourse, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer reportedly told his caucus that "nothing is off the table for next year.”

For some, that may mean reshaping the table itself. Some Democrats are considering trying to increase the number of seats on the high court. Such “court packing” plans may be feasible but are highly controversial.

Why are there nine justices?

Why We Wrote This

Legal scholars caution that efforts to “pack the court” could launch a tit-for-tat fight over the least-political branch of the government. But there are other paths that would avoid blowing up the Supreme Court.

There haven’t always been. Article III of the U.S. Constitution, which describes the judiciary, is so spare that the court’s purpose and size has morphed over time.

“It's rather striking how little there is in the Constitution about the courts as opposed to about Congress or the presidency,” says Adam Levitin, a professor of law at Georgetown University in Washington. “It's like it was an afterthought for the founders.”

The number of justices began at six, proportional to the number of circuits – or regions – in the judiciary. Each circuit had its own justice, and as the country expanded the court did as well.

The court grew to its largest during the Civil War, when President Abraham Lincoln added a 10th justice. Afterward, Congress chose to shrink the court by one justice rather than cooperate with the besmirched President Andrew Johnson. The court has since remained at nine.

No changes in structure were again considered until the Supreme Court struck down several of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s marquee New Deal programs in 1935 and 1936.

With more programs on the line, Roosevelt proposed a two-part bill to get his way. One provision reinstated pensions for retiring justices. Another would have added a seat to the court for every justice over 70-and-a-half who didn’t retire – potentially inflating the court to 15 seats.

Though Democrats held enormous majorities in the House and Senate, Congressional leaders considered this scheme an overreach and passed only the pension plan. That alone enticed one conservative justice to retire, and some believe the entire debate encouraged the court to rule more favorably on FDR’s programs – though this fabled “switch in time that saved nine” is debated. In the next few years, Roosevelt appointed seven of the nine justices on the court.

In part due to the backlash against this plan, changing the court’s size wasn’t seriously considered again until Republicans blockaded Merrick Garland’s nomination in 2015.

What are the implications of new calls to pack the court?

Ordinary legislation is enough to change the Supreme Court’s size. But such political meddling is a dangerous venture. It was disastrous for FDR and it could be for Democrats again today, says Lucas Powe Jr., a professor of government at the University of Texas at Austin School of Law and former clerk for Justice William O. Douglas.

Even with public outcry over perceived minority rule, such a change would “leave some bitter people – sore losers,” says Professor Powe.

That resentment could provoke a game of Congressional brinkmanship, or “an endless cycle of tit-for-tat court-packing accompanying successive changes in party control of the political branches,” writes Barry Cushman, University of Notre Dame professor of law, political science, and history, in an email.

It could also blight the court’s legitimacy, he writes, and perhaps tear apart fragile coalitions in Congress today.

Are there alternatives to court packing?

Yes. Politicians on both sides have suggested imposing an 18-year term limit on justices, so that two would be replaced every four-year presidential term, bringing predictability to the appointment process. Rep. Ro Khanna, a California Democrat, in September proposed such a bill, though experts question whether it would require a constitutional amendment.

Congress could also curtail the court's jurisdiction through a rarely used constitutional power – effectively letting Congress declare certain laws unreviewable by the high court. But doing so would be certain to launch new legal battles.

And in a more sweeping reform, Professor Levitin has proposed expanding the court to 33 justices and randomly picking three-justice panels for each case. This plan, he says, offers a bipartisan path from the winner-take-all structure of today’s court and could help mollify the now-contentious nomination process.