South Dakota seeks to strengthen victim-centered criminal justice

Loading...

| Sioux Falls, S.D.

South Dakota voters enthusiastically passed "Marsy's Law" in 2016, joining several states that embraced the constitutional amendments giving crime victims such rights as being notified of developments in their cases. Now voters are being asked to support changes to the amendment to help police and prosecutors cut down on unforeseen bureaucratic problems it has created.

The proposed changes – which the Marsy's Law campaign supports – would require victims to opt in to many of their rights and specifically allow authorities to share information with the public to help solve crimes. The changes will go before South Dakota voters during the state's June 5 primary election, months before voters in at least five other states decide whether to adopt their own versions of Marsy's Law.

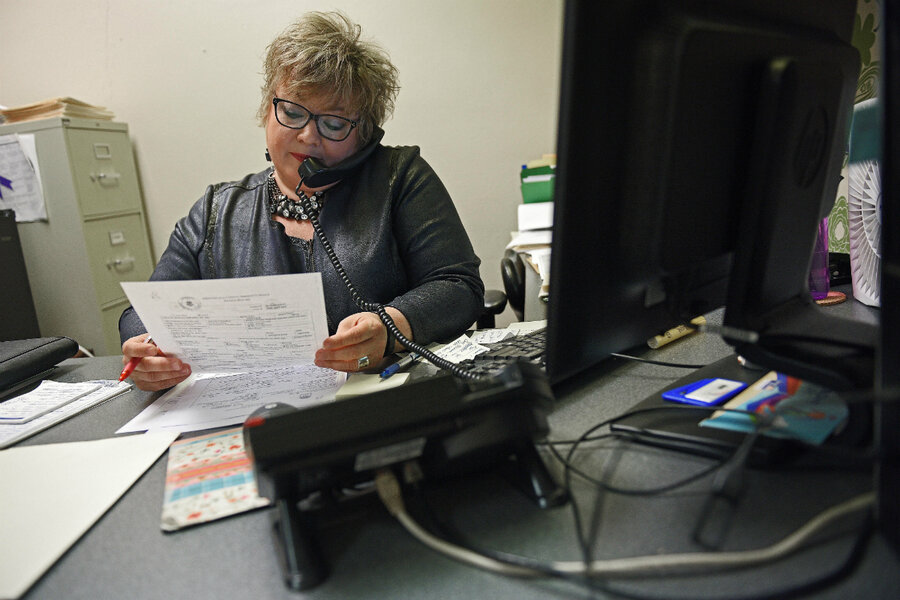

Kelli Peterson, a victim and witness assistant in the Minnehaha County State's Attorney's Office, used to spend her workdays focused almost exclusively on helping victims of violent crime navigate the criminal justice system. Since the state's Marsy's Law took effect, though, she's had to spend more time calling and mailing victims, including businesses, to let them know about court proceedings in their cases, even for petty theft or trespassing. For example, she says she spent nearly an entire day last year trying to notify an out-of-state bank that someone had been arrested for trespassing in a Sioux Falls home it owned. She ended up sending a letter but never heard back.

"It means that we get to spend less time with our really high-risk ... victims," Ms. Peterson said.

Five states – California, Ohio, Illinois, North Dakota, and South Dakota – have a Marsy's Law on their books. South Dakota would be the first to alter its law, though Montana voters passed a Marsy's Law in 2016 that the state Supreme Court later overturned, citing flaws in how it was written.

They're named after Marsalee "Marsy" Nicholas, a California college student who was stalked and killed in 1983 by an ex-boyfriend. Her brother, billionaire Henry Nicholas, has bankrolled the ballot measures. Voters are set to decide on Marsy's Law measures in November in Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Nevada, and Oklahoma.

After it passed in South Dakota, at least three large counties hired new people to work with victims. Privacy provisions in the amendment have curtailed the information that some law enforcement agencies release to the public to help solve crimes, and officials say prosecutors' offices must now track down and notify a broader swath of victims about their cases.

House Speaker Mark Mickelson initially proposed getting rid of the amendment but instead reached a deal with the Marsy's Law campaign during this year's legislative session. The group is contributing financial support to promote the passage of the proposed changes to the law.

"People voted for it the first time, and we're fixing some of the unintended consequences," Mr. Mickelson said. "It strengthens victims' rights. If you were for it before, you're for it again, and if you had some concerns about it before, it's better now."

Minnehaha County Sheriff Mike Milstead said the amended measure would specifically allow authorities to publicly release the locations or business names where crimes occur, which his office has generally stopped doing since Marsy's Law took effect.

"Every armed robbery where a business name was not able to be put out, it impacted," Mr. Milstead said. "If we're not able to say that it was this business, and people remember that they saw someone come out of that business, it's made it more difficult to get tips and solve that crime."

Pennington County State's Attorney Mark Vargo, whose office added four employees at an annual cost of more than $200,000 because of Marsy's Law, supports the changes. He said he thinks they'll help as fewer people opt in to the measure's coverage.

Supporters of the new amendment are educating voters through grassroots work and digital and direct mail advertising, with the potential for television and radio, said Ryan Erwin, a strategy consultant for the Marsy's Law for All campaign.

"This is a group of people that haven't always seen eye-to-eye on everything, and really do now," Mr. Erwin said. "I know there's a genuine desire to get this passed to help law enforcement and continue to protect victims' rights."

This story was reported by The Associated Press.