Why Virginia is giving voting rights back to ex-felons

Loading...

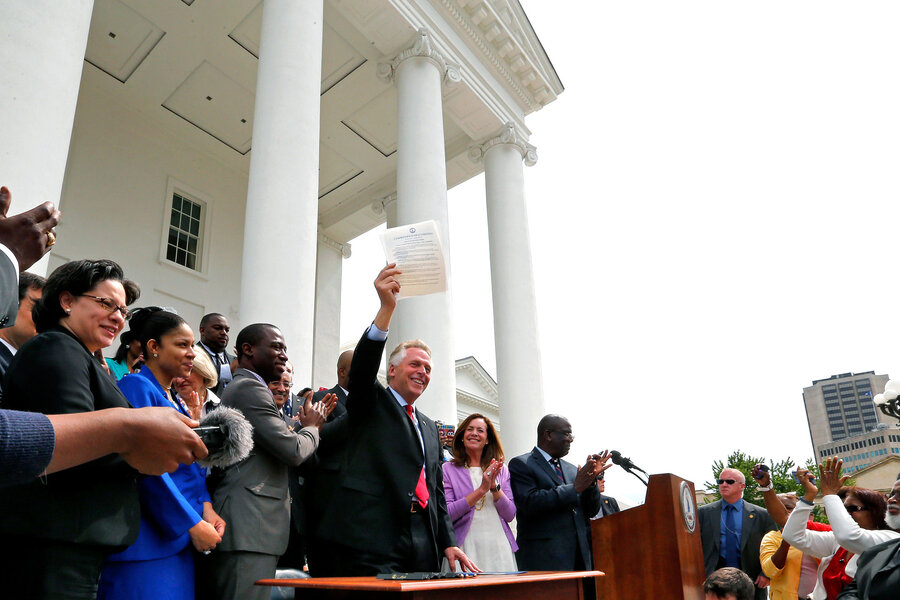

Virginia is granting more than 200,000 convicted felons the right to vote in the November elections, part of a large-scale effort Gov. Terry McAuliffe (D) says is intended to reverse the state's long history of suppressing the voting rights of African-Americans.

The move, part of an executive order Governor McAuliffe signed Friday, expands voting rights to every Virginia felon who has completed their sentences and any supervised release, parole, or probation by Friday.

It will also allow ex-offenders to run for public office, to serve on a jury, and to become a notary public. The denial of rights has a particularly bitter history in Virginia, which is seen as a crucial swing state, the governor says.

"Too often in both our distant and recent history, politicians have used their authority to restrict people's ability to participate in our democracy," he said in a statement. "Today we are reversing that disturbing trend and restoring the rights of more than 200,000 of our fellow Virginians, who work, raise families and pay taxes in every corner of our Commonwealth."

The move echoes a concern in several other states, which have increasingly turned away from harsh criminal sentences and raised new questions about what happens to offenders once they are released, including their ability to participate fully in society. In Virginia, 1 in 5 African-Americans is disenfranchised, according to the Sentencing Project based in Washington, D.C.

In February, the Maryland State Senate overrode a veto by Republican Gov. Larry Hogan and expanded voting rights to 40,000 ex-offenders. In that the case, the law actually went further than Virginia’s policy by allowing ex-convicts to vote while on parole or probation, The Christian Science Monitor's Cathleen Chen reported.

But the policies have been controversial and provoked a partisan divide. Last December, newly elected Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin (R) reversed an executive order by his Democratic predecessor to grant voting rights to ex-felons in the state once they had completed their sentences.

Governor Bevin framed his opposition to the executive order signed by then-Gov. Steve Beshear (D) on procedural rather than ideological terms.

"While I have been a vocal supporter of the restoration of rights, for example, it is an issue that must be addressed through the legislature and by the will of the people," he said in a statement.

Overall, nearly 6 million Americans aren't allowed to vote because of laws disenfranchising former felons, the Sentencing Project estimates. Maine and Vermont are the only states that don't restrict the voting rights of convicted felons.

In Virginia, McAuliffe said he is certain that he has the authority to grant a massive extension of voting rights, having previously consulted with legal experts including Attorney General Mark Herring. The administration estimates that about 206,000 people will be affected by the new order.

His effort was quickly opposed by the state's Republican-led legislature, accusing the governor of a "transparent effort to win votes," The New York Times reports.

"Those who have paid their debts to society should be allowed full participation in society," John Whitbeck, the party’s chairman said in a statement. "But there are limits," he added, saying the governor’s blanket restoration of rights, even to offenders who have "committed heinous acts of violence," was "political opportunism."

Previously, the governor had restored the voting rights of more than 18,000 felons. While the new order will not apply to felons released in the future, the governor's aides say he will issue similar orders each month to cover more offenders, the Times reports.

"People have served their time and done their probation," McAuliffe told the Times. "I want you back in society. I want you feeling good about yourself. I want you voting, getting a job, paying taxes. I'm not giving people their gun rights back and other things like that. I'm merely allowing you to feel good about yourself again, to feel like you are a member of society."

This report contains material from the Associated Press.