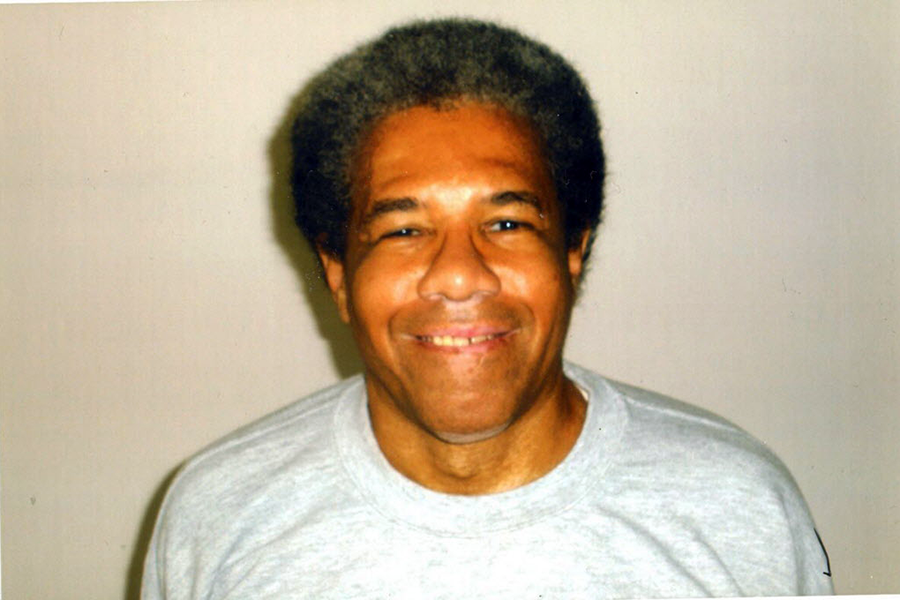

Albert Woodfox and the rethinking of solitary confinement in America

Loading...

| Atlanta

The Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola opens its doors to the public once a year for a prison rodeo, but visitors have never seen an inmate named Albert Woodfox mingling by the stables.

Instead, Mr. Woodfox, whose conviction for murdering a prison guard during prison unrest in 1972 has twice been overturned, spent most of his four-decade-long sentence at Angola in solitary confinement, alone in a small cell for 23 hours a day. On Monday, a judge cited “the prejudice done onto Mr. Woodfox by spending over forty years in solitary confinement” as one reason he will be released, and why the state will be barred from trying him a third time.

Amid global scrutiny of a practice that the United Nations has equated in many cases to torture, the Woodfox case is one example of how the United States is taking a hard look at how prison officials use “the box,” as it’s sometimes called, to maintain order and safety behind the razor wire.

Solitary confinement began in the 1800s as an opportunity for biblical self-reflection, but it has become – especially since the murder of two Marion, Ill., prison guards in 1983 – a go-to punishment for problem inmates, who may end up spending years alone, talking to the walls.

According to estimates, between 25,000 and 80,000 US inmates are in solitary at any one point. Overuse of solitary, while in many ways understandable, is problematic because recidivism rates – and suicide rates – are higher for solitary inmates.

And so as America contemplates a broader shift away from harsh punishments like the death penalty and shows renewed interest in reducing the cost burdens of prisons, states from Maine to California are starting to at times dramatically limit the use of isolation.

“Solitary confinement is something that ought to be used as a last resort, because I don’t think it promotes mental health, so you’re not creating better citizens [upon release],” says Paul Robinson, an expert on criminal sentencing at the University of Pennsylvania Law School in Philadelphia. But at the same time, he says, “sometimes there are very good reasons [for using solitary] because for some people, solitary confinement is the only responsible way to incarcerate them.”

Calls for reform began as early as 2009, but have picked up pace as legislators and prison officials confront the ethics and expenses of creating large supermax prisons that rely on loneliness and despair to rehabilitate hard cases.

In the past few years, Maine has cut its solitary population by half, in part by reducing the average stay from three months to two weeks. In 2013, then-Gov. Pat Quinn of Illinois closed the Tamms Correctional Center, which had only solitary units, largely because of its annual $26 million price tag. New York State no longer allows prison officials to send anyone who is pregnant or under 18 to solitary cells, and moves are afoot to eliminate solitary for anyone under 21 at New York City’s Rikers Island. In South Carolina, where some prisoners have spent years alone for breaking prison rules, the maximum time in solitary has been reduced to 60 days, even for numerous, but related, infractions.

And last year, California complied with a federal judge's order and began removing an estimated 2,500 mentally ill inmates from stark solitary confinement cells to less punitive isolation units. The new policy came after a series of inmate hunger-strike protests against solitary confinement at the state's notorious Pelican Bay State Prison.

Although hard statistics are difficult to tease out of state prison reports, there is evidence that such reforms work. When Mississippi dramatically reduced the number of solitary prisoners in Unit 32, its supermax facility, after a series of violent incidents in 2007, skeptics feared violence would increase. But replacing solitary with better facilities, including a new basketball court, resulted in far less violence.

Prison wardens, when polled in the early 2000s, said that using the box was crucial to “increasing ... safety, order, and control throughout prison systems and incapacitating violent or disruptive inmates,” according to a study by Daniel Mears, a Florida State University criminology professor.

Yet Christopher Epps, the former Mississippi prison chief who oversaw reforms at Unit 32, has summarized its use another way: While prison wardens start out isolating prisoners who scare them, they eventually start using it for inmates they’re “mad at,” as he was quoted in a 2012 New York Times article.

Professor Robinson says that a push to eliminate solitary altogether is “silly,” at least until anti-punishment activists are willing to spend some time inside America’s more notorious cellblocks. That, however, doesn’t mean that US prison officials can’t do a better job of making sure that solitary punishment is “proportionate” to the infraction, he says.

Robinson adds that the large number of mentally ill prisoners in US facilities is putting “prison authorities in a tough spot, because justice takes into account aggravations and mitigations, but dealing with people who are mentally ill distorts [that] system in many bad ways.”

To be sure, proportionality figured into the case of Woodfox, the Angola prisoner. Long having argued that his harsh punishments were payback for his political activism as a Black Panther leader inside the prison, Woodfox may be released as early as this week. Louisiana’s attorney general, however, has indicated he is filing an appeal. For now, Woodfox remains in isolation, but now has access to a TV.

“Solitary – in theory, a punishment for the worst of the worst, inmates who pose an immediate threat to others – has become a routine disciplinary tool, used in ways for which it was never intended,” wrote Emily Bazelon in The New York Times Magazine earlier this year. “The good news is that this is beginning to change ....”