Prosecution rests in penalty phase of Tsarnaev trial with emotional crescendo

Loading...

| Boston

On their last day of witness testimony, the prosecution in the Boston Marathon bombing trial wanted to bring a moment from one of the worst acts of domestic terrorism in almost two decades up to a life-sized scale.

The twin bombings have been pored over for months in this trial. There is little the jury hasn’t already seen regarding the case, including the haunting picture of the bomber, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, “lurking” behind a crowd before planting his pressure cooker bomb.

Still, over numerous objections from the defense, the prosecution brought out a large white banner with a scanned image of a sidewalk grate. The picture was a scale replica image of the grate where Mr. Tsarnaev placed the bomb — and where the Richard family, including 8-year-old victim Martin Richard, were watching the marathon on April 15, 2013. It had been replicated from the “lurking” picture by FBI Boston field photographer Michelle Gamble, who took the stand as a witness this morning.

“What are those people standing on?” asked a prosecutor.

“A grate,” replied Ms. Gamble.

“Is that grate there now?” the prosecutor asked.

“No.”

“Why not?”

“It was blown into several pieces.”

Prosecutors then began to choreograph the final moments before the bomb detonated. A prosecutor took the position of Martin Richard, while Gamble took the position of the bomb on the mock “grate.”

“Can you measure distance between the bomb and Martin Richard?” asked the prosecutor.

“I’d say about 3.5 feet,” replied Gamble.

Yet as dramatic as Gamble’s testimony was, the prosecution focused much of their last day of testimony in the penalty phase on survivors instead of victims.

The prosecution called 15 witnesses over the past three days — a fraction of the 92 witnesses called over 15 days in the trial’s first phase. The jury heard from the friends and family of Krystle Campbell and Lingzi Lu, who were both killed in the blasts, as well as those of Sean Collier, the MIT police officer who was fatally shot by Tsarnaev and his older brother Tamerlan several days later.

Both Ms. Campbell's and Mr. Collier’s fathers and brothers testified, and Lu’s aunt testified after revealing that Lu’s parents were “too devastated” to travel from China to testify.

No family members took the stand Thursday. The first witness of the day was Marc Fucarile, a survivor who lost a leg to the second bombing.

His testimony covered the actual bombing only briefly before moving on to his lengthy rehabilitation. Mr. Fucarile described the 45 days he spent in the hospital.

Fucarile said that the number of surgical procedures he’s had since the bombings are “in the high sixties” – and could possibly keep rising as his right leg is still “salvageable.”

“Where were you earlier today?” asked a prosecutor in court this morning.

“At Walter Reed Army Medical Center, where I’m continuing my treatment,” Fucarile replied.

“Have your doctors suggested to you when there might be an end in sight?”

“No,” he replied again, quickly.

Fucarile finished his testimony and rolled down from the witness stand, his route to the exit taking him immediately past Tsarnaev. Both men ignored each other as Fucarile – familiar with his wheelchair for the better part of two years now — barely slowed on his way to the exit.

On the day of the bombing, Fucarile and Tsarnaev wouldn’t have been much further apart than they were today. The next witness of the day – Heather Abbott – was probably only a few feet down the sidewalk from Tsarnaev, waiting to get into the Forum restaurant to meet friends.

“As I reached for my ID the first bomb went off,” she said.

Everyone around her flinched, and then a moment later the second bomb went off.

“I was catapulted through the front doors of the restaurant,” she said, where she said she fell “into chaos.”

Ms. Abbott was later taken to Brigham & Women’s Hospital, where she ultimately decided to have her leg amputated.

“It was probably the hardest decision I’ve ever had to make in my life,” she added.

Before she left the stand, the prosecution asked her to name some survivors in roughly a dozen photographs from a slideshow displayed to the courtroom.

One survivor wasn’t included in the slideshow, and he was the last witness of the day.

Steve Woolfenden began his Marathon Monday 2013 with “normal, day-to-day” activities with his son, Leo: eating breakfast, brushing their teeth, eating lunch. Then they headed down to the marathon to watch his wife, Amber, finish.

As he worked his way, falteringly, through his story, the tension steadily built up in the courtroom. Mr. Woolfenden described how he drove into Boston and parked near Boston Common before walking toward the finish line on Boylston Street to meet friends at a restaurant.

“I’m no longer unfamiliar with Boylston Street. At the time I was very unfamiliar with Boylston Street,” he told the prosecutor.

He ended up on the wrong side of Boylston. In the process of trying to get to the other side of the street, the first bomb went off near the finish line.

“When first bomb detonated what did you try to do?” asked a prosecutor.

“I was in shock and disbelief, then it registered that we had to get out of there,” Woolfenden replied. “The most logical idea was to do 180 and head in other direction. But we couldn’t.”

“Why couldn’t you?”

“Because the second bomb went off.”

At first he thought he was still standing, he added, but soon realized that was just because he was still holding onto the stroller carrying Leo. He immediately tried to check on Leo and found he was mostly OK, save for a cut on his head and some minor burns. Then he tried to stand up again.

“That’s when I realized my leg had been severed,” he said.

As he sat there on Boylston Street, unable to move, a procession of people came up to him offering help and screaming encouragement. Woolfenden was eventually able to hand Leo off to Boston Police Officer Thomas Barrett – a picture of the two eventually making the cover of TIME Magazine.

Still unsure if his wife was alive, Woolfenden was transferred to an ambulance soon after, an ambulance he shared with another survivor: Rebekah Gregory DiMartino.

“While you were in the ambulance, could you hear Ms. DiMartino saying anything?” asked the prosecutor.

“She was screaming, in intense pain,” Woolfenden replied.

“What did you do then?”

“I asked her to give me her hand.”

“Why did you do that?”

“Because I wanted to hold somebody’s hand,” said Woolfenden.

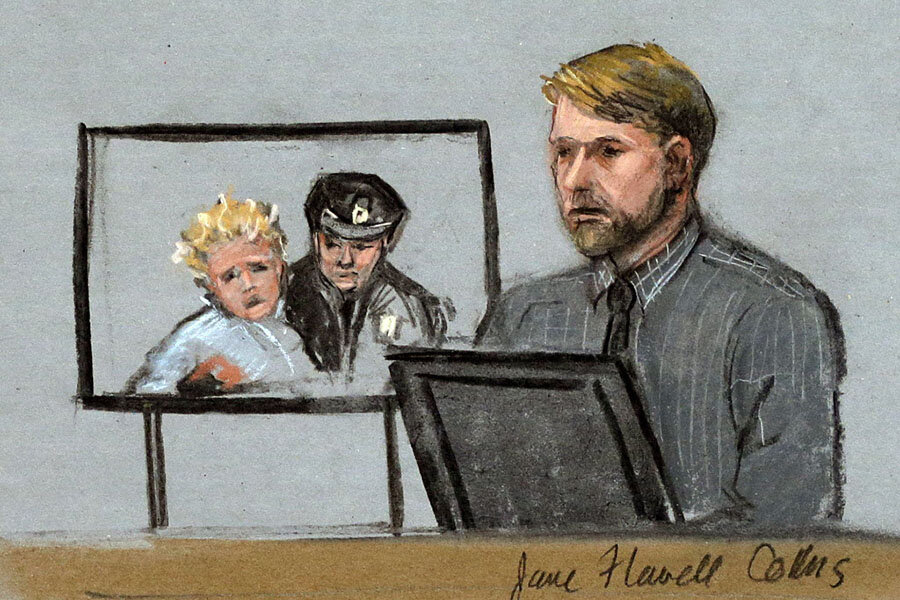

Near the end of his long and emotional testimony, prosecutors returned to the video taken from next to Forum during the bombings. Prosecutors slowed the video down to seconds before the bomb detonated, then they asked Woolfenden to identify himself. He did so.

Then they pointed out a second man in the dense crowd on the sidewalk, a man in a white hat. Dzhokhar Tsarnaev.

“Do you remember seeing the man in the white hat that day?” asked the prosecutor.

“Not that I recall,” Woolfenden answered.

The video moved forward a few seconds and the crowd suddenly ducks and looks up the street, where the first bomb had just detonated.

“Where is the man in the white hat at this moment?” asked the prosecutor.

“Standing next to me,” Woolfenden replied. Tsarnaev was also walking in the opposite direction as Woolfenden in that moment, away from the Forum and away from Marc Fucarile, Heather Abbott, and dozens of other witnesses who faced Tsarnaev from the witness stand during the trial.

“Did the man in the white hat bump into you that day?” asked the prosecutor.

“No, not that I recall," replied Woolfenden.

A few seconds later a blinding flash engulfs the screen. After the smoke cleared, Woolfenden was visible on the group next to the stroller. As fate would have it, he was also next to Martin and Denise Richard.

“What could you hear from them?” asked the prosecutor.

“I could hear ‘Please’ and ‘Martin’ from Denise Richard,” said Woolfenden.

“What did you do?”

“I put my hand on her back, and she turned to me and said, ‘Are you OK?’ ” Woolfenden replied.