Etan Patz case: Despite confession, a trial would be tricky

Loading...

| New York

Pedro Hernandez, the confessed killer of Manhattan schoolboy Etan Patz 33 years ago, may never go to a jury – if he sticks to his confession and is found to be mentally competent.

In that event, a judge will simply set a sentencing date after Mr. Hernandez undergoes extensive psychological testing.

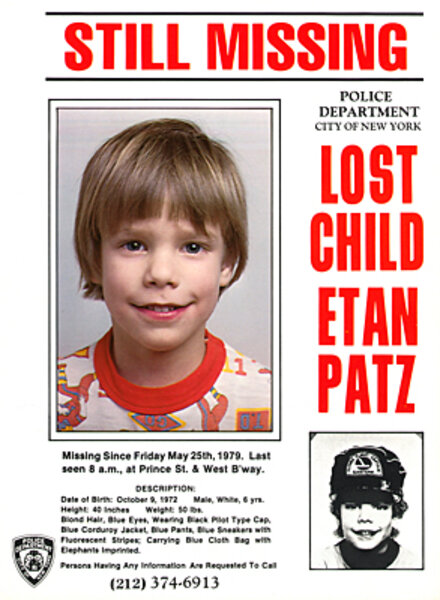

If that happens, it will be the final chapter in a case that riveted much of the nation in 1979, when Etan, then 6 years old, never made it to school on the first day he was allowed to walk there on his own. At first, he was assumed to be lost. Then speculation arose that Etan had been kidnapped. His photo – showing his infectious smile and blond locks – appeared on milk cartons around the nation. The case reminded many of the kidnapping of Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s son back in 1932.

However, if Hernandez were to change his mind and recant his confession, prosecutors would face a difficult decision: whether to put him on trial without corroborating evidence other than the confession.

Young Etan’s body has never been discovered. According to the New York Police Department, who charged Hernandez on Thursday with second-degree murder, the suspect said he placed the youngster’s body in a bag that was deposited in the trash. A month later, Hernandez, who was then 18, moved out of the city.

The key issue will be Hernandez's mental state at the time of the confession. “If he recants his confession, then it’s an issue of what level of confidence the district attorney and the police have in the original confession,” says former federal prosecutor Alan Kaufman, now a partner at the law firm Kelley Drye in New York. “If he is psychologically unstable and there is no independent evidence, the district attorney may not be confident he is the killer.”

To determine Hernandez's mental state when he confessed to the killing, mental health professionals will question him. On Friday, according to press reports, Hernandez was being examined in Bellevue Hospital, which has a robust mental-health division, and had been placed on suicide watch. He had not yet met with his court-appointed attorney, and it was unclear at time of writing whether his arraignment originally scheduled for Friday would take place.

According to press reports, the confession was videotaped in Camden, N.J., where Hernandez was first questioned. NYPD detectives were among those present during the interview.

The fact that the confession was videotaped “makes the confession more powerful,” says James Cohen, a defense attorney and a professor at Fordham Law School in New York. “It is less subject to claims [that] the police were feeding the subject information known to the police but also only known to the killer.”

In missing person’s cases and potential murder cases, the police try to hold onto a piece of evidence that is known only to them and the alleged killer, says Mr. Kaufman. If someone claims to have committed the crime but repeats only information that has appeared in the newspapers, the confession is considered less credible.

Law enforcement officials "would test the confession with something like that,” says Kaufman.

According to NYPD Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly, Hernandez took police detectives to the location where he allegedly committed the crime. Hernandez appeared remorseful and glad to finally confess to it, said Mr. Kelly. However, it’s still not clear why the boy was murdered.

“There had to be something more involved; it would be part of the questions asked of Hernandez,” says Kaufman.

However, the possibility of false confession cannot be overlooked. “There is the phenomenon of false confessions, where people just confess for reasons people find inexplicable,” says Mr. Cohen. “So his testimony will be examined by psychologists to see how much it squares up with what is known about false confessions.”

For example, after the Lindberghs' 20-month-old son was kidnapped and murdered, more than 100 people went to the police and confessed, says Kaufman. The actual murderer, Bruno Hauptmann, was found two years later and was ultimately executed in New Jersey in 1936.

If Hernandez were to plead not guilty, Kaufman wonders whether the case would ever go to trial. “Reconstructing the crime 33 years later is very difficult,” he says. “You would have to go back and talk to everyone in that neighborhood to see if anyone remembers seeing Hernandez with Etan when he disappeared. It’s a long shot.”

Cohen, however, expects that prosecutors would proceed even if Hernandez were to recant. “The prosecutor is in it for gold unless God intervenes,” he says.