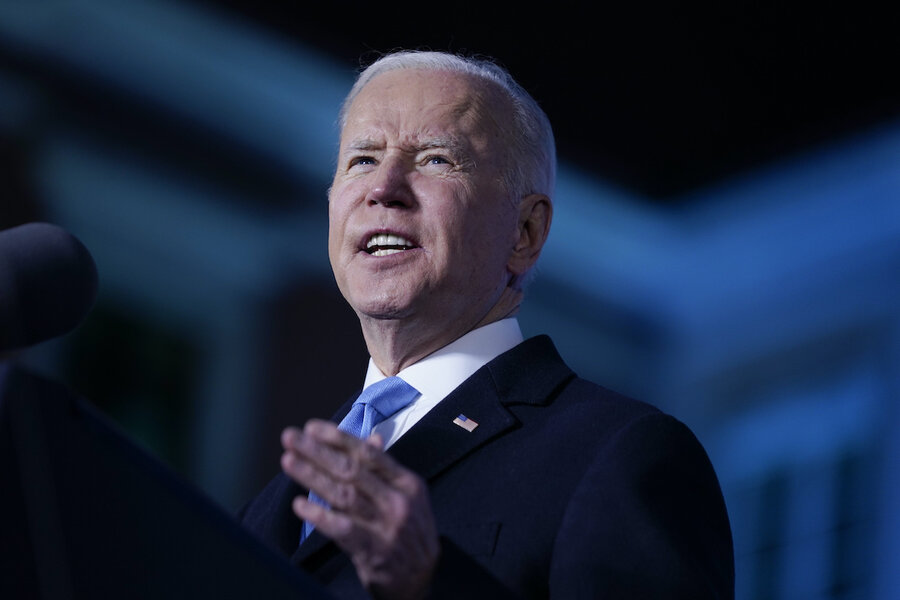

In Poland address, Biden says Putin 'cannot remain in power'

Loading...

| Warsaw, Poland

President Joe Biden said Saturday that Vladimir Putin “cannot remain in power,” dramatically escalating the rhetoric against the Russian leader after his brutal invasion of Ukraine.

Even as Mr. Biden’s words rocketed around the world, the White House attempted to clarify soon after Mr. Biden finished speaking in Poland that he was not calling for a new government in Russia.

A White House official asserted that Mr. Biden was “not discussing Putin’s power in Russia or regime change.” The official, who was not authorized to comment by name and spoke on the condition of anonymity, said Biden’s point was that “Putin cannot be allowed to exercise power over his neighbors or the region.”

The White House declined to comment on whether Mr. Biden’s statement about Mr. Putin was part of his prepared remarks.

“For God’s sake, this man cannot remain in power," Mr. Biden said at the very end of a speech in Poland's capital that served as the capstone on a four-day trip to Europe.

Mr. Biden has frequently talked about ensuring that the Kremlin's invasion, now in its second month, becomes a “strategic failure” for Mr. Putin and has described the Russian leader as a “war criminal." But until his remarks in Warsaw, the American leader had not veered toward suggesting Mr. Putin should not run Russia. Earlier on Saturday, shortly after meeting with Ukrainian refugees, Mr. Biden called Putin a “butcher.”

Mr. Biden also used his speech to also make a vociferous defense of liberal democracy and the NATO military alliance, while saying Europe must steel itself for a long fight against Russian aggression.

Earlier in the day, as Mr. Biden met with Ukrainian refugees, Russia kept up its pounding of cities throughout Ukraine. Explosions rang out in Lviv, the closest major Ukrainian city to Poland and a destination for the internally replaced that has been largely spared from major attacks.

The images of Mr. Biden reassuring refugees and calling for Western unity contrasted with the dramatic scenes of flames and black smoke billowing so near the Polish border – another jarring split-screen moment in the war.

In what was billed by the White House as a major address, Mr. Biden spoke inside the Royal Castle, one of Warsaw's notable landmarks that was badly damaged during War II.

He borrowed the words of Polish-born Pope John Paul II and cited anti-communist Polish dissident and former president, Lech Walesa, as he warned that Mr. Putin's invasion of Ukraine threatens to bring “decades of war.”

"In this battle we need to be clear-eyed. This battle will not be won in days, or months, either,” Mr. Biden said.

The crowd of about 1,000 included some of the Ukrainian refugees who have fled for Poland and elsewhere in the midst of the brutal invasion.

“We must commit now, to be this fight for the long haul,” Mr. Biden said.

Mr. Biden also rebuked Mr. Putin for his claim the the invasion sought to “de-Nazify” Ukraine. The president of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelensky, is Jewish and his father’s family died in the Holocaust.

“Putin has the gall to say he’s de-Nazifying Ukraine. It’s a lie,” Mr. Biden said. “It’s just cynical. He knows that and it’s also obscene.”

Mr. Biden also tried to tie the invasion to the former Soviet Union’s history of brutal oppression, including the post-World War II military operations to stamp out pro-democracy movements in Hungary, Poland, and what was then Czechoslovakia.

The president defended the 27-member NATO alliance that Moscow says is increasingly a threat to Russian security. He noted that NATO had worked for months through diplomatic channels to try to head off Russia's invasion.

The war has led the U.S. to increase its military presence in Poland and Eastern Europe, and Nordic nations such as Finland and Sweden are now considering applying to join NATO.

“The Kremlin wants to portray NATO enlargement as an imperial project aimed to destabilize in Russia,” Mr. Biden said. “NATO is a defensive alliance that has never sought the demise of Russia.”

After meeting with refugees at the National Stadium, Mr. Biden marveled at their spirit and resolve in the aftermath of Russia’s deadly invasion as he embraced mothers and children and promised enduring support from Western powers.

Mr. Biden listened intently as children described the perilous flight from neighboring Ukraine with their parents. Smiling broadly, he lifted up a young girl in a pink coat and told her she reminded him of his granddaughters.

The president held hands with parents and gave them hugs during the stop at the soccer stadium where refugees go to obtain a Polish identification number that gives them access to social services such as health care and schools.

Some of the women and children told Mr. Biden that they fled without their husbands and fathers, men of fighting age who were required to remain behind to aid the resistance against Mr. Putin's forces.

“What I am always surprised by is the depth and strength of the human spirit,” Mr. Biden told reporters after his conversations with the refugees at the stadium, which more recently had served as a field hospital for COVID-19 patients. “Each one of those children said something to the effect of, 'Say a prayer for my dad or grandfather or my brother who is out there fighting.'"

The president spent time reassuring Poland that the U.S. would defend against any attacks by Russia as he acknowledged that the NATO ally bore the burden of the refugee crisis from the war.

“Your freedom is ours," Mr. Biden told Poland's president, Andrzej Duda, earlier, echoing one of that country's unofficial mottos.

More than 3.7 million people have fled Ukraine since the war began, and more than 2.2 million Ukrainians have crossed into Poland, though it is unclear how many have remained there and how many have left for other countries. Earlier this week the U.S. announced it would take in as many as 100,000 refugees, and Mr. Biden told Mr. Duda that he understood Poland was “taking on a big responsibility, but it should be all of NATO's responsibility.”

Mr. Biden called the “collective defense” agreement of NATO a “sacred commitment," and said the unity of the Western military alliance was of the utmost importance.

“I’m confident that Vladimir Putin was counting on dividing NATO," Mr. Biden said. "But he hasn’t been able to do it. We’ve all stayed together.”

European security is facing its most serious test since World War II. Western leaders have spent the past week consulting over contingency plans in case the conflict spreads. The invasion has shaken NATO out of any complacency it might have felt and cast a dark shadow over Europe.

No clear path to ending the conflict has emerged. Although Russian officials have suggested they will focus their invasion on the Donbas, a region in eastern Ukraine, Mr. Biden told reporters, when asked whether the Kremlin had changed its strategy, “I am not sure they have."

Madhani reported from Washington. Associated Press writers Monika Scislowska in Warsaw, Poland, contributed to this report.