Botched Alabama execution reignites concerns over execution drugs

Loading...

An execution in Alabama has reignited debate over the lethal injection procedure – even as some ask whether the inmate should have received the death penalty at all.

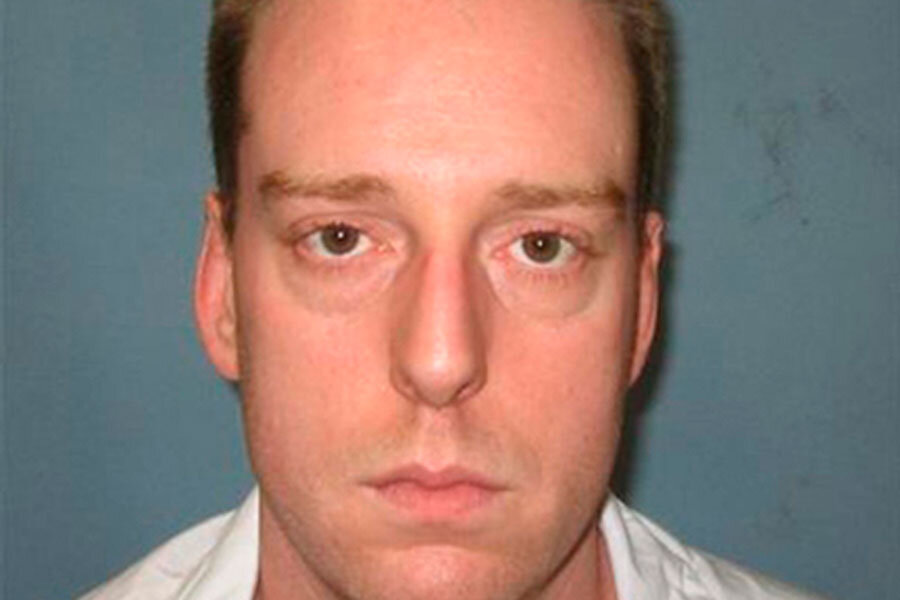

Ronald Bert Smith Jr., convicted of the 1994 murder of Huntsville, Ala., store clerk Casey Wilson, was executed on Thursday evening. It took 30 minutes for him to be pronounced dead, and 13 minutes in – when he should have been sedated – Mr. Smith heaved, coughed, and appeared to move during tests designed to confirm that he was unconscious.

For some, Smith’s movements have raised further questions about whether the sedative midazolam is effective enough to be used as part of executions by lethal injection. What's more, the very process that led Smith to the execution chamber has come under recent scrutiny.

The efficacy of the drug midazolam has been the subject of numerous appeals from death row inmates. Midazolam became the preferred sedative in multi-drug cocktails in many states since 2011, when a European Union ban prevented companies from selling sodium thiopental and pentobarbital to US states for use in capital punishment.

In appeals, Smith and others have argued that the drug is unreliable, pointing to three botched executions in 2014 – in Oklahoma, Ohio, and Arizona – as proof. In one, the Oklahoma case of Clayton Lockett, the inmate actually spoke, saying, “something’s wrong,” before dying of a heart attack 43 minutes into the procedure, rattling even staunch death penalty supporters.

Just as with Mr. Lockett’s case, Smith’s struggles may fuel debate about whether the current lethal injection protocol violates the Eighth Amendment prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment.

The US Supreme Court upheld the use of midazolam in a 5-4 decision in July 2015, saying that increased dosage and monitoring procedures like consciousness checks have addressed the problem, The Christian Science Monitor's Warren Richey reported. But the consciousness checks may not have prevented Smith from suffering.

“He’s reacting,” one of his lawyers whispered during the procedure, according to the Associated Press, perhaps indicating that Smith was not as deeply unconscious as he should have been.

Alabama Corrections Commissioner Jeff Dunn said he did not see any reaction to the consciousness tests, AP reported. But he said that an autopsy will be done, adding that he hopes this will reveal any irregularities.

Smith's case has also shined a spotlight on Alabama's unusual death penalty law.

When he was convicted in 1995, the jury voted 7-5 for life imprisonment. But in Alabama, judges can override a jury’s recommendation, and the judge sentenced him to death instead.

Alabama's death penalty law is an outlier among states that allow for capital punishment, The Marshall Project reports:

"Thirty-one states have the death penalty, and 30 of them require unanimity from a jury in crucial phases of sentencing. Not in Alabama, where a jury can impose a death sentence with a vote of at least 10 to 2. The jury may also recommend life imprisonment, as it did in Smith's case, but the judge can overrule jurors' findings no matter what they decide."

During appeals, Smith’s lawyers argued that a judge alone should not be able to impose the death penalty, an argument supported by legal advocates Patrick Mulvaney and Katherine Chamblee of the Southern Center for Human Rights.

Mr. Mulvaney and Ms. Chamblee argued in an August Yale Law Journal article that politics can influence judges’ decisions: in tough-on-crime states which elect their judges, like Alabama, there may be pressure to sentence an individual to death.

And though there’s little debate over whether Smith committed the crime (which was captured on video), at least three Alabama inmates sentenced to death by judges after juries had recommended life imprisonment were later exonerated.

Similar issues have led to court cases like Hurst v. Florida, which led Delaware and Florida to end judicial override and require juries to be unanimous if they choose to sentence a defendant to death. Alabama maintains that its law is constitutional, though the US Supreme Court twice paused Smith’s execution to consider whether the penalty had been applied constitutionally in his case.

This report contains material from the Associated Press.