Is Texas's strictest-in-the-nation voter ID law discriminatory?

Loading...

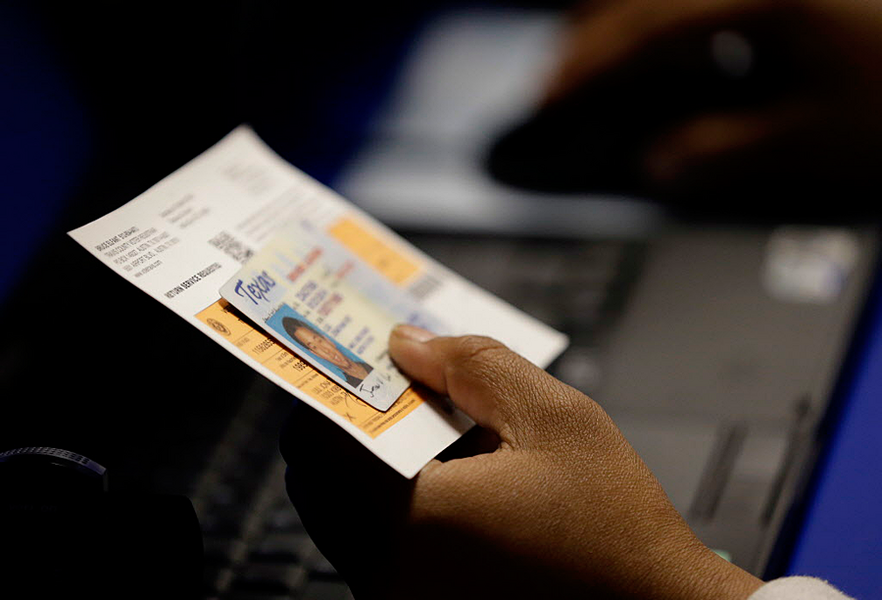

Judges on a federal appeals court are considering the need to soften Texas's strictest-in-the-nation voter ID law, which opponents argue discourages turnout among Hispanics, African Americans, and other minorities.

On Tuesday, the New Orleans-based Fifth US Circuit Court of Appeals heard arguments from Scott Keller, the Texas solicitor general, and Janai Nelson, representing the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, about whether the law, which specifies which forms of identification voters must show, violates the Voting Rights Act.

The panel of 15 judges indicated it was not interested in striking down the law, but questioned why Texas, unlike other states with similar laws, didn't include provisions for registered voters who lack the now-required forms of identification, as The Washington Post reported.

Any action the court takes could end a five-year debate about whether the law's strictness preserves the integrity of elections there, or is a discriminatory strategy meant to repress votes from demographics less likely to have the required forms of ID, which include drivers licenses, passports, military IDs, and gun licenses.

Yet a political science professor at the University of California, San Diego, indicates the answer is irrelevant so long as the law stands.

"If we want a more open and inclusive democracy, voter ID laws are detrimental to those goals," Zoltan Hajnal tells The Christian Science Monitor in a phone interview. "They do discriminate against racial and ethnic minorities, and that could be a real problem."

In researching the effect of stricter voter ID laws, Dr. Hajnal found they resulted in lower minority turnout. That finding is consistent with a 2014 study by the US Government Accountability Office, Barry Burden, a political science professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who testified in 2014 against the Texas law, tells the Monitor.

Texas has long required voters to show a form of identification. But the bill then-Gov. Rick Perry (R) signed in 2011 restricted the types of ID allowed, which now includes a driver's license or concealed handgun license, but excludes a college or tribal ID.

At the time, states with a history of voting rights discrimination were barred from adopting election laws that could affect minorities unless federal officials or judges approved them, according to The Post. But in 2013, the Supreme Court "threw out Congress's designation of which states required pre-clearance" in Shelby County v. Holder, and Texas quickly instated its previously-blocked law.

Ever since then, the law has been at the center of a legal back-and-forth. In October 2014, a district judge struck it down, but a panel for the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals issued a preliminary injunction against the district court's ruling. The Supreme Court has turned down a request to review the case, but recommended that the Circuit Court of Appeals act before late July, according to The Post.

The state maintains the law is a way to stamp out voter fraud, which Gov. Greg Abbott (R) said other states aren't willing to enforce.

"What I find is that leaders of the other party are against efforts to crack down on voter fraud," Governor Abbott said, according to The Texas Tribune. "The fact is that voter fraud is rampant. In Texas, unlike some other states and unlike some other leaders, we are committed to cracking down on voter fraud."

But opponents say the law has impacted 600,000 registered Texas voters who are believed to lack the required form of identification.

"Our state continues to prey on the rights of minorities with the voter identification law, which needlessly burdens the right to vote of thousands of people, particularly those of color," Gary Bledsoe, president of the Texas NAACP, said in a statement.

The laws, and others like it, are targeting the wrong type of fraud, however, says Dr. Burden: they aim to prevent impersonation at polls, which he calls the "riskiest," with the "least payoff." Instead, he says, Texas and other states should develop stricter systems for verifying absentee ballots.