Love letters on my laptop

Loading...

I find the love letters exactly where I left them: in a folder in an old Hotmail account. Years ago, I named that folder “Home.”

I must have weeded those e-mails out of my main inbox on a not-very-busy morning in Harare, Zimbabwe, sitting in front of a clunky desktop computer in the thatched round cottage that was our first home together.

“Home” is not a big folder. We got married six months after we met. Three of those months we spent mostly together: first in Zimbabwe, where he lived, and then in Paris, where I was working. That didn’t leave much time for writing each other heartfelt missives of love and longing.

And yet. Quickly I scroll through the subject lines. The door to my office is open. I can hear my husband clanking the lid down on a saucepan. “Plump Pigeons,” reads one of them – oh yes, I remember. “Correction to Clarity.” “Lots of PSes.”

I used to buy phone cards to call my soon-to-be-husband in Harare every night after my editing shift at a French news agency was over. I’d wait my turn in line outside the phone booths near the Sacré-Coeur, then tap +263 (the calling code for Zimbabwe), and hold my breath for the connection.

I think I did most of the talking.

Those “PSes” were things he hadn’t had a chance to say during five-minute, $15 conversations.

He calls now from the kitchen. “What do you put on the potatoes?”

I direct him to the turmeric and turn back to my laptop.

There it is, right at the bottom of the list, dated July 28, 2000. The first message he ever sent me. I’d landed in Paris a day earlier, back from the reporting trip that my editor certainly hadn’t intended to become a matchmaking mission.

I skim through the message, grinning again at the way the man I would marry – whose precise writing I still love – poked fun at his “ponderous prose.”

Now that I try to count those e-mails, my cursor slipping up and down, I see that there are more than 40 of them.

Each one was crafted thoughtfully, every single word weighed before he pressed Send. In contrast, my messages to him were news briefs, three- or four-paragraph replies banged out at the end of my shift.

I did not have a computer in the tiny flat I rented, with its view that stretched out as far as the Tour Montparnasse. I had to read his messages quickly, reviewing the passages I’d managed to memorize on the metro ride home.

There is a wail from a bedroom. The wooden beads that our 3-year-old daughter is threading have slipped off the string. “Mummy is busy,” I hear my husband say.

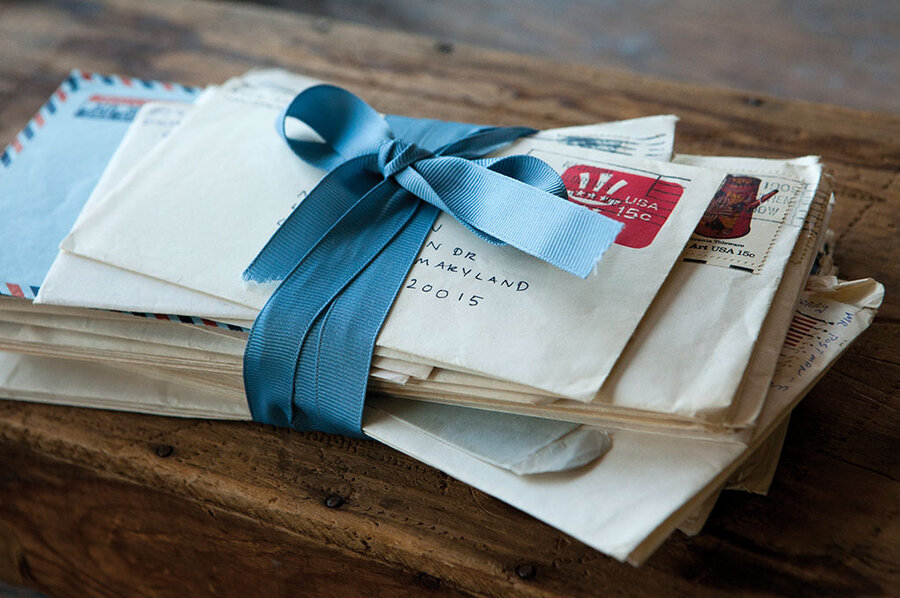

My mother’s love letters are in the bottom of a low chest of drawers by her bed. They are written on thick cream Basildon Bond paper in my father’s strong hand. Years ago, Mum must have decided to store them all in one place, just as I did. Hers are tied together, not in a virtual file but with a thin piece of ribbon.

She keeps them near to the flat burgundy box that holds her jewelry from the 1960s: a glittery brooch, the broken-off buckle from a belt.

My mother likes to be able to hold her letters. When I started to e-mail her from university, she said she preferred “letters I can take out of my handbag.”

I think about her words now as I stare at my love letters, neatly stacked by date and time in an electronic cupboard. Would I prefer them to have been written on paper?

I don’t think so. I might have mislaid them in a move or ruined them with water from a knocked-over cup. Online, they are as pristine as they were the day they were written.

Still, I’m not taking any chances. I select each message in turn and press Forward to send it to another e-mail account. No harm in having backup copies.

I close my laptop and get up from the desk. The spinach is ready. All I need to do is to mix in a bit of cheese, some stock, and two eggs and then slide the whole thing under the broiler.

Supper for four. That’s what my husband’s prose, painstakingly tapped out in Times New Roman, has led to.

“I found Dad’s love letters to me,” I announce a little later, serving spoon in hand.

My husband snorts, secretly pleased. “Did you actually keep those things?”

Sam, age 11, looks up from editing photos of his puppy. He’s not yet at the age of drafting love letters. Nor is he far enough into teenagerhood to find the idea of his parents having a life before him totally uninteresting.

I look at him. At some point, he, too, will live and love online.

“One day I’ll e-mail you a line or two so you can see it on your screen,” I say.