A thirst for words

Loading...

"Can I look at your magazine, Sam?" Brian asks.

Sam, his baby sister, and I are sitting under a thatched shelter on the outskirts of the Matopos National Park, a boulder-strewn landscape in dry southern Zimbabwe. Outside, the sand shimmers gray-gold in the midday sun.

It is too hot to do anything but read.

We are camping. At night, in our borrowed tent, we shiver. Twice in our week-long trip, Sam climbs into my sleeping bag, huddling close to me for warmth. It is a sturdy bag. But it is no match for the near-desert conditions – or for two people.

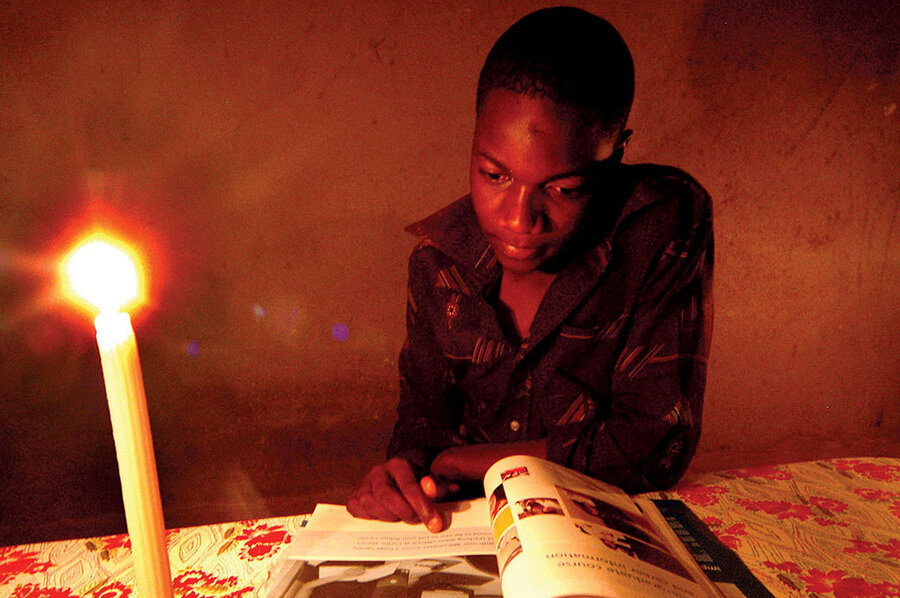

Sam's magazine is a copy of South Africa's Popular Mechanics, bargained for at a flea market in the Zimbabwean capital, Harare, during the presidential elections in July. Though the pages are torn and the edition dates back to 2009, it still cost us US$1. Prices in Zimbabwe are relatively high. New books are a luxury that many forgo. In a country where only 30 percent of the people are formally employed, money must go first for food, school fees, and utility bills.

Sam, age 9, loves to read. So, too, it appears, does campsite attendant Brian, who lays the fire each evening and can tell us when leopards last wandered within yards of our campsite.

The Matopos is a harsh place. Water is scarce. There is little cellphone reception. If Brian wants to talk to his wife, he must climb a kopje – one of the strange castlelike mounds of stones that the rock dassies bask on – to place a call.

Today, as a breeze stirs the overhanging grasses of the thatch, Brian tells me about his family. His 15-year-old, who lives nearly 30 miles away in Bulawayo, has just had a tooth out. The talk turns to the elections, won once again by longtime President Robert Mugabe.

After a four-year coalition government, Mr. Mugabe's return to power has deepened animosity between his party and the opposition.

"If I support one party – not the same one as my neighbors – I think we should not be angry with each other," Brian says. "We can live in peace."

He thumbs through the pages of Popular Mechanics. Sam watches, sensing a familiar need.

During Zimbabwe's decade-long economic and political crisis, when shortages and price controls left supermarket shelves empty (except for toilet paper, which bizarrely never ran out), I made up stories for Sam when I couldn't buy him books. Shona friends slipped me baked sweet potatoes and asked if I had "something new to read." Hunger can take many forms.

"You can borrow the magazine," Sam says suddenly to Brian.

I wish I'd brought books. Our car was so loaded with sleeping bags, diapers, and saucepans that Sam's father imposed strict limits on reading matter. So I packed our new e-reader, a present from my parents, only to find, when we arrived, that the battery was nearly dead.

We now have precisely one magazine each to last the week.

Back home in eastern Zimbabwe, I still share books as I can. "These are in good condition," the librarian at a sparsely stocked city library enthused as I handed over an Umberto Eco and a Kate Kerrigan. A memory flickers: a small library in rural Lincolnshire, England, where I spent many afternoons reading as a child. My parents did not often buy me books, but they made sure I had access to acres of them.

Books here take journeys of their own: a friend passes "Does This Church Make Me Look Fat?," by Rhoda Janzen, on to an elderly Irish nun who's spent decades here. My copy of "Writing Still – New Stories From Zimbabwe" travels nearly 200 miles across the country from a mother to a 30-something daughter who works in the hotel industry.

Passing along books is a tiny thing, a drop in the ocean when so many want stories. But I know it's worth it when I think of Fadzie, in her last year of primary school, who has read every Enid Blyton and Dick King-Smith book I've found for her.

"I want to be an author," she told me the other day.

As Sam and my husband pull up tent stakes at the end of our vacation, I hurry awkwardly after Brian, our magazines in my hands.

• Readers wishing to send books to Zimbabwe may send an e-mail to homeforum@csmonitor.com for details. Put "Books for Africa" in the subject line.