Honoring Leonardo da Vinci, the master who never stopped experimenting

Loading...

| London

Two things consistently fascinated Leonardo da Vinci: the mechanics of flight and the movement of water. His mind was like both, swiftly flowing but occasionally pooling to encompass depths beneath the surface.

At the 500th anniversary of his death, scholars, art lovers, and the public are taking a far-reaching look at his career. Exhibitions in Italy and England, as well as the largest-ever survey of his work, which opens at the Louvre Museum in Paris this fall, are celebrating the master’s achievements not only in art but also in science.

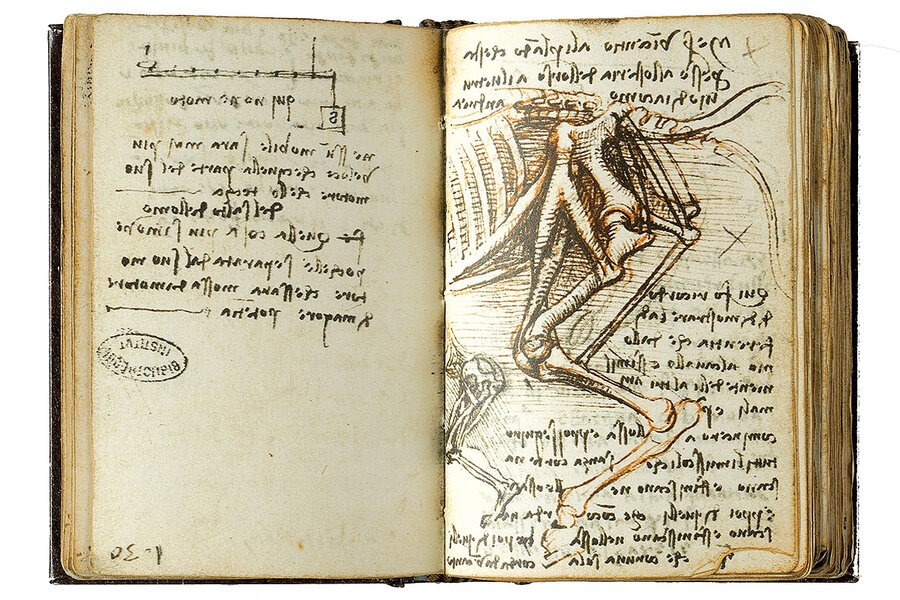

One of those exhibitions, of Leonardo’s drawings, is attracting multitudes to the Queen’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace in London. “Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing” displays the full range of Leonardo’s elastic mind at work. It conveys a life in process, a man and mind on a continuous learning curve, endlessly observing, studying, thinking, reflecting. The drawings – more than the finished paintings – show him improvising and experimenting, much more than just recording reality.

Why We Wrote This

What drives people to continuously learn? Leonardo da Vinci was constantly observing, studying, reflecting. Five hundred years after his death, exhibitions and books examine the path the Renaissance man took to creativity.

As someone who appreciates Leonardo da Vinci’s painting skills, I’ve long marveled at how crowds rush past his most sublime painting, “The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne,” to line up in front of the “Mona Lisa” at the Louvre Museum in Paris.

The art critic in me wants to say, “Wait! Look at this one. See the poses of entwining bodies and gazes, the melting regard of the mother for her child, the translucent folds of cloth, the baby’s chubby legs.” It’s a perfect combination of humanity and divinity.

Now, at the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death, scholars, art lovers, and the public are taking a far-reaching look at his career. Exhibitions in Italy and England, as well as the largest-ever survey of his work that opens at the Louvre this fall, are celebrating the master’s achievements not only in art but also in science.

Why We Wrote This

What drives people to continuously learn? Leonardo da Vinci was constantly observing, studying, reflecting. Five hundred years after his death, exhibitions and books examine the path the Renaissance man took to creativity.

One of those exhibitions, of Leonardo’s drawings, is attracting multitudes to the Queen’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace in London. “Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing” displays the full range of Leonardo’s elastic mind at work.

The main impression conveyed by “A Life in Drawing” is of a life in process, a man and mind on a continuous learning curve, endlessly observing, studying, thinking, reflecting. The drawings – more than the finished paintings – show him improvising and experimenting, much more than just recording reality.

You see his beginnings as a talented apprentice to sculptor Andrea del Verrocchio in Florence, then his 16 years (1483-99) at the court of Ludovico Sforza in Milan, during which he sketched hundreds of horses rearing or cantering, viewed from all angles, to prepare for an unrealized equestrian monument. Sforza valued Leonardo’s skills as a set designer of elaborate court pageantry and masques, which meshed perfectly with Leonardo’s love of fantasy.

While in Milan he also produced “The Last Supper” fresco (1495-98), which still astounds. In his studies for heads and limbs of the apostles in the exhibition, you see the psychological reactions of each to Jesus’ announcement that one of them will betray him. A drapery study of the twisted arm of St. Peter, who leans over Judas’ shoulder in the fresco, shows Leonardo’s brilliant use of subtle shading in charcoal; both cloth and flesh are arrested in mid-movement.

Upon his return to Florence, he was celebrated as a genius. It was there he and the younger sculptor Michelangelo faced off in a sort of “Florence’s Got Talent” contest. Both designed frescoes (abandoned unfinished) on opposite walls of a palazzo, with the ever-charming Leonardo trying to befriend the grumpy Michelangelo.

Leonardo’s last years (1516-19) were spent in France as the guest and resident sage of King Francis I. There, he kept refining and revising his paintings, including the “Mona Lisa” and the Saint Anne painting.

His scientific investigations into anatomy, astronomy, geology, botany, light, and movement were all done to represent life truthfully in his art. Leonardo saw both the micro and macro versions of the world. In our age of extreme specialization, such a universal approach is an inspiration.

Two things consistently fascinated him: the mechanics of flight and the movement of water. His mind was like both, swiftly flowing but occasionally pooling to encompass depths beneath the surface.

So many works are non finito, not finished, the cause of much regret by connoisseurs. But Leonardo himself was never finished. Each endeavor was a precursor to further investigation.

That quality may explain why, 500 years after his death, viewers are still not finished with him. There’s always more to see and understand.