The Oscar goes to ... HAL? Why AI is at center of Hollywood strike.

Loading...

| Culver City, Calif.

Hollywood producers won’t be able to rely on Google Bard to spit out the next “Shakespeare in Love” anytime soon. Nonetheless, screenwriters were alarmed when studios refused to discuss the issue of artificial intelligence during negotiations for a new contract.

“If AI is filling in the blanks of your story based on all of what’s come before – you know, it has access to every book ever written, every movie ever made ... then how do we get anything new and original?” says Jessica Sharzer, who wrote the screenplay for “A Simple Favor.” “Will you ever end up with ‘Everything Everywhere All at Once’ by clicking a button?”

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onCan – should – creativity be manufactured? What provides the spark of inspiration? Those questions might seem philosophical for a picket line, but screenwriters say they are existential in a time of artificial intelligence.

The Writers Guild of America doesn’t want to ban AI as a tool. But it does want to prevent studios from using it to partially or completely write scripts. Studios want flexibility to utilize the rapidly evolving technology. The disagreement boils down to economic compensation. But writers on the picket lines view AI as an existential threat. The question about whether humans and their creativity are dispensable is one that reverberates across other sectors of society.

“Is there something fundamentally unique about humans?” asks Mike Wolmetz of the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University. “There are things that are unique. Can they be replicated? We will see.”

Can ChatGPT write the next big summer blockbuster?

When The Monitor asked the artificial intelligence chatbot to create a science fiction comedy featuring a soccer team and father-and-son relationships, it instantly concocted a plot.

“The year is 3001,” begins the synopsis, “and the intergalactic soccer team of the United Galactic Alliance (UGA) are on the brink of the biggest game in the galaxy – the Intergalactic Cup.”

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onCan – should – creativity be manufactured? What provides the spark of inspiration? Those questions might seem philosophical for a picket line, but screenwriters say they are existential in a time of artificial intelligence.

The team’s star player, Zane, is a handsome astronaut. The inciting incident? Zane discovers he has a half-brother, Max, who is the son of a rival space captain.

“Worse yet, it turns out that Max is the star player of their rivals – the Dark Side, a team of alien miscreants bent on galactic domination,” continues the storyline. Zane must decide whether to help Max win the Cup and make his father proud or ensure UGA wins and safeguard the galaxy from the Dark Side.

The outline concludes: “Zane and Max struggle to reconcile their newfound relationship as they face off in the most important match in intergalactic history.”

It’s doubtful that this generic storyline would cause the agents for Austin Butler and Timothée Chalamet to scramble to buy the movie rights. But here on Earth, a real-life, high-stakes conflict is playing out between two teams. A major reason why Hollywood screenwriters are striking against studios is because they fear that artificial intelligence will usurp their jobs.

The Writers Guild of America (WGA) doesn’t want to ban AI as a tool for scriptwriting. But it does want regulations to prevent studios from using AI to partially or completely write scripts. The studios, who are represented at the bargaining table by the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP), want flexibility to utilize the rapidly evolving technology. The disagreement boils down to economic compensation. But writers on the picket lines view AI as an existential threat. The question about whether humans and their creativity are dispensable is one that reverberates across other sectors of society.

“Is there something fundamentally unique about humans?” asks Mike Wolmetz, program manager for human and machine intelligence in the Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. “There are things that are unique. Can they be replicated? We will see.”

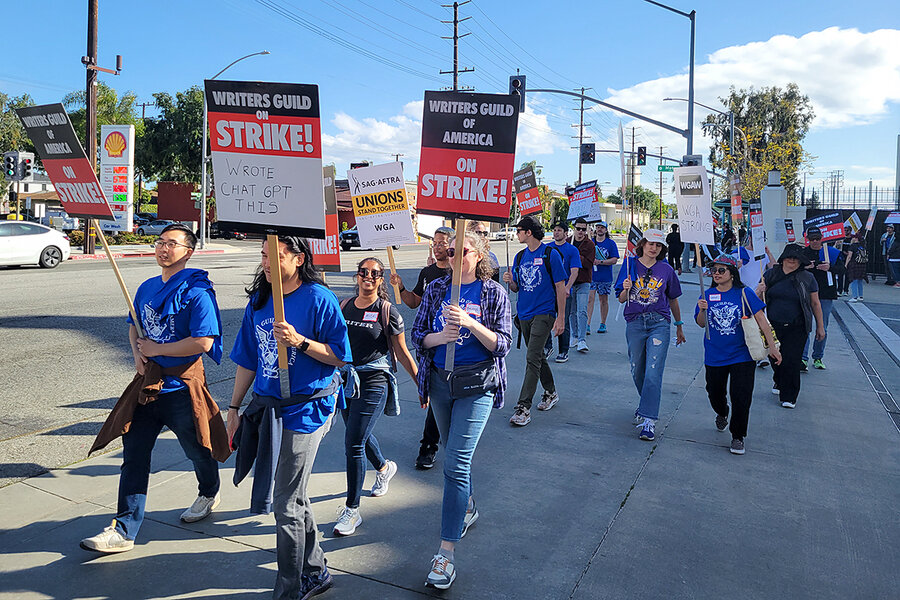

Outside Hollywood studios, it’s common to see striking writers carrying placards such as “Alexa will not replace us” and “Wrote ChatGPT this.”

“The entire reason why we’re out here, in my opinion, is rooted in corporate greed, but also this idea of introducing AI to replace us,” says Kira Talise, a writer protesting outside Sony Studios in Culver City. “We are the people who write the content that makes these companies billions of dollars. ... It’s really disheartening to be undervalued in this way and for it to be perceived that we could just be replaced by computers.”

If some writers’ views of artificial intelligence most closely resemble Sarah Connor’s in “The Terminator,” others are embracing the technology. In Berlin, Tristan Wolff used AI to develop a pitch for an episode of a crime series on German television. The production company was looking for fresh ideas for their long-running show. So they fed ChatGPT a general template of the drama and who the characters are. Mr. Wolff says that the producers in the room laughed when the AI tool offered up story ideas, because most of them were similar plotlines as hundreds of other episodes. Yet it also generated two ideas that they were excited to develop into scripts.

Mr. Wolff publishes articles on Medium about how to interact with AI to write scripts. He starts by feeding ideas into AI so that it will “hallucinate” a story.

“If you want the AI to plot it out, you would have to have a longer prompt, which gives it more dramaturgical constraints and more information about the characters, their flaws and dreams,” says the writer in a Zoom interview. “Even then, it’s not guaranteed that it creates a good story, but it might create something that’s interesting enough for you to work with.”

AI is a language-processing tool that is trained to predict the next word or sentence in a dialogue or a stream of text. You experience AI every time you start typing and a suggestion pops up with possible wording to complete the rest of the sentence. It anticipates how to respond by calculating probabilities of which words are most likely to come next. AI does this by scraping the Internet for data. For all their formidable abilities, AI tools still have limitations – for now, at least.

“They don’t have an episodic memory like you have,” says Mr. Wolmetz, the scientist from APL. “They don’t have the formal reasoning that we have. They don’t have factual world knowledge.”

Phillip Berg, a Danish writer and director who lives in the Canary Islands, believes that AI is no substitute for the human mind when it comes to creating unique stories. He does, however, believe AI can help. Mr. Berg recently launched AI ScreenWriter, a tool that he likens to a sparring partner for writers. AI ScreenWriter can plot a three-act structure that follows a template for beats in a story. It can also generate scenes that incorporate characters’ traits and motivations.When it comes to dialogue, AI may be great at mimicking HAL from “2001: A Space Odyssey,” but it’s a long way from replacing Aaron Sorkin.

“Creating the way a person talks is super nuanced, and AI is not going to completely replace any writers doing that,” says Mr. Berg in an interview via Zoom.

That’s one reason Hollywood producers won’t be able to rely on Google Bard to spit out the next “Shakespeare in Love” anytime soon. Nonetheless, screenwriters were alarmed when the AMPTP refused to discuss the issue of AI during negotiations with the WGA.

“Their chief negotiator, Carol Lombardini, said as plain as day, ‘I’m not going to restrict the technology I might want to use at some point,’” says WGA negotiating committee co-chair Chris Keyser during a break from marching outside Fox studios on a recent afternoon. “It’s too simple for them to put a writer in a room with a machine. ... As I often say, ‘The machine making it inhumanly fast and the writer making it humanly good, replace 90% of us.’”

The AMPTP’s only comment on the issue has been via a May 4 press release.

“We value the work of creatives. The best stories are original, insightful and often come from people’s own experiences,” the AMPTP wrote. “AI raises hard, important creative and legal questions for everyone. ... So, it’s something that requires a lot more discussion, which we’ve committed to doing.”

Some have dubbed AI a “plagiarism machine.” For that reason, studios may be leery to accept AI-reliant pitches and scripts that could leave them open to lawsuits.

“If AI is filling in the blanks of your story based on all of what’s come before – you know, it has access to every book ever written, every movie ever made, and all of those scripts – then how do we get anything new and original?” says Jessica Sharzer, who wrote the screenplay for the Anna Kendrick and Blake Lively comedy thriller “A Simple Favor,” as well as a sequel that is in pre-production. “Will you ever end up with ‘Everything Everywhere All at Once’ by clicking a button?”

Then again, many mainstream blockbusters draw from existing and fairly predictable paradigms. Think, for example, the thousands of iterations of the Cinderella story. But if a writer hopes to use AI to create a story that stands out – or is eligible for copyright – the script will still have to modify or arrange AI-generated material in a creative way. The key to avoiding generic outcomes is creating unusual prompts for AI to work with.

The capabilities of artificial intelligence are also likely to grow in leaps and bounds. APL’s Mr. Wolmetz isn’t aware of benchmarks that track growth in AI creativity. However, he observes, until recently, ChatGPT didn’t do well on LSAT exams. Now it scores in the 90th percentile.

It’s one thing for machines to mimic happiness, sadness, jealousy, anger, shame, or desire. It’s something else altogether to create a script that leaves a lasting impression because it authentically reflects real-life experiences, which can be messy and contradictory. Those kinds of stories require authors to mine their inner recesses.

“When I write, I always think about the emotional journey first, because the plot points are completely random until they have an emotional weight to them,” says Ms. Sharzer, who believes AI is a useful tool for scriptwriters but is a long way from being able to track a character’s interior evolution. “We are thinking on a plot level because that’s the easiest level to grab on to. But Meg LeFauve, who was one of the writers on ‘Inside Out,’ talks about ‘the hot lava.’ That is the thing that you don’t really want to touch. That’s deep down under the surface of yourself. That is the place where all the good ideas are.”