Religious leaders preach radical hospitality – even after church shootings

Loading...

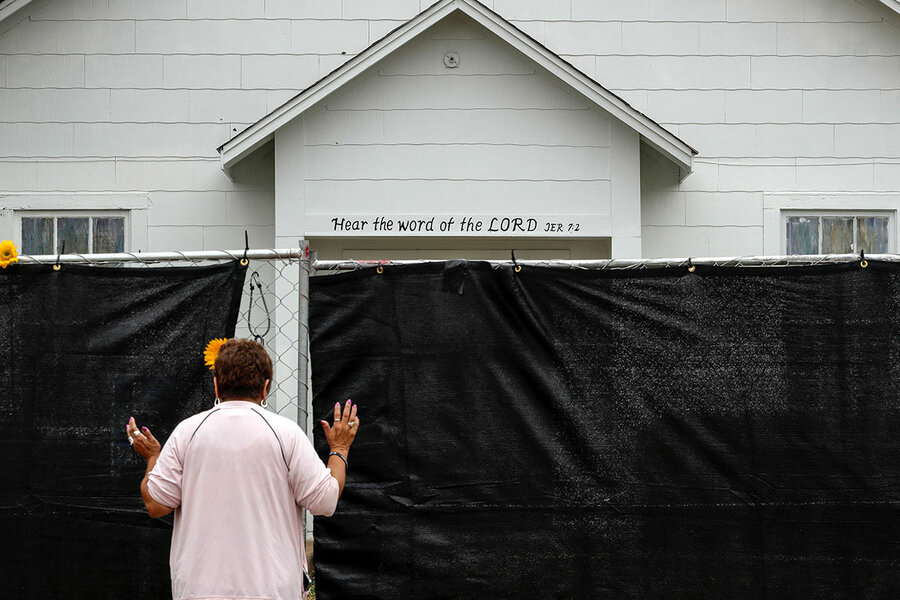

Headlines about mass shootings such as this week’s tragedy in which a gunman shot and killed five people in a Sacramento church are sparking intense debate over how to protect places of worship, and whether to allow guns inside sacred spaces.

“If people are afraid to come together, then their religion becomes much, much weaker,” says Jeremy Yamin, director of security and operations at the Massachusetts nonprofit Combined Jewish Philanthropies. Fences, cameras, and security guards might help regular worshippers feel secure but risk inhibiting an open-armed welcome to visitors.

Why We Wrote This

Mass shootings in houses of worship are statistically rare, but create a conundrum for reconciling security with spiritual mission. Leaders are allaying fear with fresh thinking on practical security, conscious engagement with community, and staying centered on sacred mission.

And yet, these contentious dilemmas have spurred fresh thinking among churches, mosques, and synagogues. Religious leaders say conscious efforts to engage with the broader community, be security wise, and stay centered on sacred mission are the best way to answer the fundamental question at issue: How to allay fear?

“The best security is engagement with the larger community,” says Saif Rahman, spokesperson for the Dar Al-Hijrah Islamic Center in Falls Church, Virginia. “The more we’re able to essentially fight ignorance with information and bring light to understanding, the less likely someone will decide to take it upon themselves to attack a religious center.”

The man with a backpack slipped unnoticed into the church auditorium. He carefully chose his moment. The congregation of First United Methodist Church in New Braunfels, Texas, was engrossed in watching a presentation when he interrupted proceedings. Unzipping his backpack, the intruder dressed in camo-fatigues quickly assembled a firearm with practiced precision. People cowered in the pews.

Then it dawned on the congregation that the interloper was a part of the security demonstration they’d been watching.

“People complained afterwards,” admits Gary Kirkham, a congregation member who helped create the church’s safety program by consulting experts and police. “A lot of this stuff is just too realistic for some people.”

Why We Wrote This

Mass shootings in houses of worship are statistically rare, but create a conundrum for reconciling security with spiritual mission. Leaders are allaying fear with fresh thinking on practical security, conscious engagement with community, and staying centered on sacred mission.

Their jitters – as well as the security exercise itself – are understandable. In 2017, a man from New Braunfels drove to a church in nearby Sutherland Springs and fatally shot 26 people. Headlines about tragedies such as that one – and a shooting Feb. 28 in a Sacramento, California, church in which five people died – create a conundrum for churches, mosques, and synagogues reconciling security with spiritual mission.

Fences, cameras, and security guards might help regular worshippers feel secure but risk inhibiting an open-armed welcome to visitors. There’s intense debate, too, over whether protective measures should include guns inside sacred spaces.

And yet, these contentious dilemmas have spurred fresh thinking. Conscious efforts to engage with the broader community, be security wise, and stay centered on sacred mission, say religious leaders, are the best way to answer the fundamental question at issue: How to allay fear?

“There’s an existential threat to Judaism and to religion which is that if people are afraid to come together, then their religion becomes much, much weaker,” observes Jeremy Yamin, who as director of security and operations at the Massachusetts nonprofit Combined Jewish Philanthropies helps Jewish institutions implement security.

That dilemma echoes across the U.S., which, since 1980, has experienced 11 mass murders at houses of worship. According to The Violence Project, the number of those attacks (defined by four or more victims) has grown over the past two decades. The three deadliest shootings have taken place since 2015. But, statistically speaking, mass shootings – distinct from arson or other threats – at churches are “rare events in the grand scheme of things,” says James Densley, co-founder of The Violence Project and department chair of the School of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice at Metropolitan State University in Minneapolis.

While headlines about attacks on houses of worship get chilling attention, these sites are actually no more likely to have a shooting than any other location, says Guy Russ, vice president of innovation and data at Church Mutual Insurance, the leading insurer among the nation’s 350,000 religious institutions.* What makes religious institutions vulnerable is that there’s often less security in place than at schools or government buildings.

Most shooters, according to an FBI study, select targets based on a perceived wrong that happened to them either in that place or by a person that happens to be at that place. Often, the shooters know their victims. In the latest shooting, in Sacramento, the gunman killed his three daughters, one other person, and himself.

Security training has saved lives

Houses of worship can be a target of a broad array of racial or religious hate crimes – Klan-inspired firebombings of Black churches in the 1960s being a historical symbol of that. But, while hate crimes overall increased in 2020, just 3.4% were committed in churches, synagogues, temples, and mosques.

Even so, some of the most devastating mass shootings in recent history have been motivated by animus toward religious and racial groups, magnifying public fear of the vulnerability of all churches.

In 2019, there were 51 people massacred inside a mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand, and in 2017 a white nationalist killed six people in a Quebec mosque – though there have been no mass shootings in a U.S. mosque. Eleven people were fatally shot inside a synagogue in Pittsburgh in 2018. A shooting by a white supremacist at Mother Emanuel, a Black church in Charleston, South Carolina, claimed nine lives in 2015.

Warren Mitchell, head of security for the 4,200-seat Friendship-West Baptist Church in Dallas, recalls the effect that latter massacre had on his fellow, predominantly Black congregants.

“Every congregation around the country, especially African-Americans, were all on edge because a lot of people started asking about security training,” says Mr. Mitchell, who is a Dallas Police Department sergeant. “There were some churches, like one directly across the street from us, that we’ve provided some security training for. And it made us brush up even on our security training.”

Many congregations utilize federal and state grants to boost security and implement safety drills. That training has been credited with saving lives.

When Rabbi Charlie Cytron-Walker and members of his congregation were taken hostage inside a synagogue in Colleyville, Texas, he recalled training he’d received from the FBI, the Anti-Defamation League, and Secure Community Network. It helped him calmly manage the 11-hour situation. The captives were eventually able to flee when the rabbi threw a chair at the gunman.

Though Mr. Cytron-Walker recently said he wishes that one of his fellow hostages had been carrying a gun, a former member of his synagogue alleged on Facebook that the rabbi “didn’t allow his members to be armed during services.”

“I was praying very hard that everything would be resolved in the best way possible,” says Michael Barclay, rabbi at Temple Ner Simcha in Agoura Hills, California. But he wonders if the incident would have happened at all if there had been security guards like the ones at his synagogue in California.

“There’s a great statement from Islam – they say, ‘Trust in Allah and tether your camel,’” says Rabbi Barclay. “So we have faith in God, and we tether our camel by always having people there with firearms. ... You need to create a safe physical space so that you can have a safe spiritual space.”

Many synagogues hire armed guards. It’s expensive, and many small synagogues can only afford to do so on important holidays. Another option for smaller congregations: Authorize lay members to bring concealed-carry firearms where it’s legal.

“The concept of having some of your own congregants who are trained, skilled, maintain their skills and practice, and are known to the community and known to the congregation, I don’t think it’s a bad idea at all,” says Fred Kogen, president of a mostly Jewish but secular social gun club in Southern California called Bullets & Bagels. “I don’t think self-defense of a church or synagogue should be the sole purview of the so-called experts.”

“We’re not here as bouncers”

Other denominations struggle, too, over whether guns belong inside a sanctuary. When Bethany Benz-Whittington was a pastor at a Presbyterian church in Jacksonville, Florida, the 2016 mass shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando prompted her congregation to consider allowing firearms inside the building.

“I have said, ‘If you decide to become an open-carry congregation, and if you say guns are welcome in this space, then I will no longer be your pastor,’” says Ms. Benz-Whittington. “And so then, instead of engaging the issue, everyone has said, ‘Well, then we just won’t ask.’”

Where some churches opt for a “don’t ask, don’t tell” stance, others are less equivocal. At the Rev. Hansen Wendlandt’s Presbyterian church in Sandy City, Utah, a posted sign reads “Blessed are the peacemakers. Please leave your guns elsewhere.”

Despite his fervent anti-gun outlook, Mr. Wendlandt believes it’s prudent for churches to implement security measures. At his previous post in Nederland, Colorado, says Mr. Wendlandt, an individual sent a threat to disrupt a church service. So the pastor asked two of the largest men to sit near the door, but the threat didn’t materialize.

Even so, there were other challenges. Houses of worship are, after all, havens for those in need who can bring their problems along with them.

“We had a ton of homeless ministry at that church in Nederland,” he says, noting that some congregation members were frightened by their presence. Nonetheless, he adds, safety isn’t the highest value of a denomination and it should never trump spiritual mission. His church congregation displayed patience and forgiveness toward those who were working toward healing.

“The Old Testament is rife with overprotecting,” he says, noting that the Sodom and Gomorrah story is really about welcome. “And in that case, there is this fear of the ‘other.’ I think that the wider scope of Scripture draws us to appreciate hospitality, and it’s incumbent on us to figure out where those boundaries are.”

That sort of openness isn’t without risk. At Dar Al-Hijrah Islamic Center in Falls Church, Virginia, hospitality is foundational. It feeds 400-plus families every week and offers rental assistance. Last year, a man there threatened congregants with a knife, then verbally accosted the center’s social services director, who isn’t a Muslim.

“He said, ‘Hey, you’re white. What are you doing here with these people?’” recounts Saif Rahman, director of government and public affairs at the center. “You try to balance between how you respond to this, and how do you maintain your values in making sure that this is a house of God that’s open to all.”

In New Braunfels, the First United Methodist church occasionally attracts unhoused people. Yet Mr. Kirkham says the ushers abide by Christian principles: “What would Jesus do in a case like this? You know he’d be welcoming, right?”

Even so, the security team is vigilant. Following the church massacre in Sutherland Springs, the New Braunfels church created a command center with 16 security cameras, installed a button that can instantly lock the doors, and trained an in-house team in everything from usher protocols to emergency medical care. That detailed security is low-key to the point of being almost invisible to visitors, says Mr. Kirkham.

At Friendship-West church in Dallas, Mr. Mitchell shares a similar philosophy: “We’re not here as bouncers at a nightclub. Our main thing is not to look like we are a fortress, a church that’s being guarded by police officers or security officers. We wear suits on Sunday.”

Radical hospitality

Proactive engagement is an increasingly popular strategy. Borrowing a common security practice at banks and businesses, denominations train ushers to greet every newcomer at the door. Security experts cite studies showing that approach often deters people with bad intentions from going through with their plans.

“This idea of upping the greeting game has two parts to it,” says security consultant Jeanie Garrett, author of “Open Arms, Safe Communities: The Theology of Church Security.”

“You’re making sure that they have a reason to be there. You’re asking, ‘Do you need anything? Do you know where the sanctuary is? Are there prayer requests that you have? And can I get your name and email, and we’ll follow up with you?’ On the other hand, it’s also a radical form of hospitality.”

Ultimately, the key to keeping houses of worship relatively accessible to newcomers may lie in dispelling a bunker mentality within the denomination.

“The best security is engagement with the larger community,” says Mr. Rahman, at Dar Al-Hijrah Islamic Center. “The more we’re able to essentially fight ignorance with information and bring light to understanding, the less likely someone will decide to take it upon themselves to attack a religious center.”

Another way to counter anxiety, suggest some, is to share a comforting theological outlook with worshippers.

“The opposite of fear is faith. The two cannot exist in the same place at the same time,” counsels Rabbi Barclay.

Similarly, Joseph Moore, a pastor who works for the Presbyterian Foundation, says there’s a reason that the most common command in the Bible is “Do not fear.”

“Christian worship points us beyond ourselves,” says Mr. Moore. “It points us to the God of the universe. And it reminds us that we are not centered, but that something else is centered and that there’s something freeing and unifying about that.”

* This story has been changed to correct the name of the company Church Mutual Insurance, and to clarify its share of the business of insuring houses of worship.