Beyond clichés: Teen anxiety prompts closer look at young lives

Loading...

| Acton, Mass.

Societal issues like global warming and racism weigh heavily on today’s young people. While getting good grades and fitting in socially still primarily occupy them, they also understand that there is work to be done, and that they will likely be the ones to do it. “It’s stressful to know you’re going to have to be the change,” says eighth-grader Biz Brooks from Acton, Massachusetts.

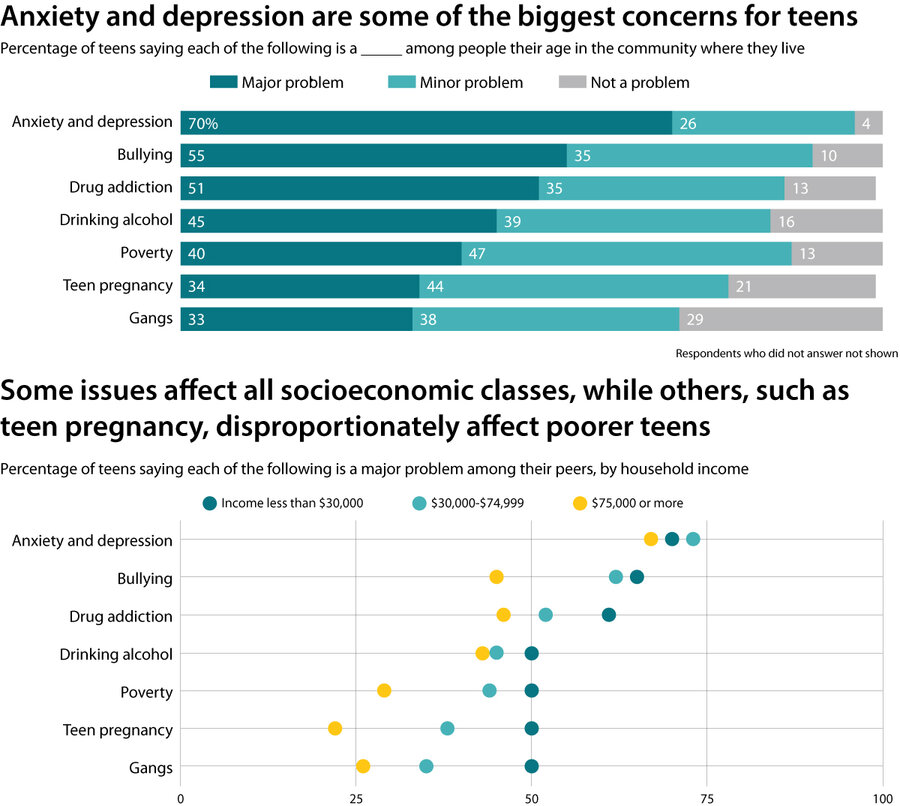

A February report from the Pew Research Center indicates that 70 percent of teens consider anxiety and depression a major problem among their peers. There’s no consensus among researchers about what drives this anxiety, although common theories include fear of failure, the rise of smartphones and social media, changing parenting styles, and a world that feels unusually chaotic.

One solution: focus on self-compassion. “I tend to teach a lot of high achievers,” says Karen Bluth, an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “They learn that it’s OK to be kind to yourself. It’s revolutionary for them. I think it’s revolutionary for adults too. It goes against a lot of what our culture teaches us.”

Why We Wrote This

A majority of young people say they feel stressed out, pointing to causes other than social media. How are adults trying to address and shift teenage thought?

Eighth-grade student Biz Brooks and her friends like to chat about K-pop music, photography, and her new dog. But when the teens hang out or send text messages on their phones, they also deal with darker thoughts.

“My friends and I talk about being anxious a lot of the time,” she says. “We talk about how things stress us out because generally we are a pretty stressed group of people.”

Biz lives with her family in Acton, Massachusetts, a prosperous suburb about 30 miles outside Boston.

Why We Wrote This

A majority of young people say they feel stressed out, pointing to causes other than social media. How are adults trying to address and shift teenage thought?

The 13-year-old may be especially attuned to mental health struggles since her town still reels from a spate of recent youth suicides. Yet new research shows her and her friends’ feelings are far from unique.

A Pew Research Center survey released in February found that 70 percent of teens in the United States consider anxiety and depression a major problem among their peers. That comes on the heels of other studies showing alarming rises in the number of anxiety diagnoses among young Americans and heightened levels of “overwhelming anxiety” in college students. With the issue starting at earlier ages and affecting all races and income brackets, efforts at solutions also appear to be rising.

Anxiety and depression among teens “is significantly worse” now says Karen Bluth, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “I get emails from parents with 11-year-olds who are super anxious.”

There’s no consensus among researchers about what drives teen anxiety, although common theories include fear of failure, the rise of smartphones and social media, changing parenting styles, and a world that feels unusually chaotic.

Biz and her neighbor Charissa Yu, a high school junior, say their anxiety stems from intense pressure to achieve good grades, attend a prestigious four-year university, and hold a successful career that makes a positive impact on the world.

“I want to tell myself that I’d be OK if I failed, but I really don’t think I would be,” says Charissa, who worries about how many advanced classes to take next year. “I definitely feel that anxiety coming up. It’s just a building pressure of ‘how much can I endure?’ ” she says.

Biz calls anxiety “an icky feeling you get that you can’t shake really easily,” and says her friends have been anxious about grades and college since sixth-grade.

‘It’s OK to be kind to yourself’

In the nationwide Pew survey of U.S. teenagers ages 13 to 17 conducted this fall, researchers found 61 percent of teens face pressure to get good grades. The second most common pressures teens report are to look good (29 percent) and to fit in socially (28 percent).

Professor Bluth co-developed a curriculum for teenagers called “Making Friends with Yourself: A Mindful Self-Compassion Program for Teens” that teaches teens how to deal with anxiety by treating themselves kindly, the way they would a friend. She runs trainings on the curriculum around the world.

“I tend to teach a lot of high achievers who have pushed themselves to get where they are and [who are] incredibly stressed and anxious to the point of sometimes being not functional,” Professor Bluth says. “They learn that it’s OK to be kind to yourself. It’s revolutionary for them. I think it’s revolutionary for adults too. It goes against a lot of what our culture teaches us.”

One of the most commonly cited reasons for increased teen anxiety is the rise of smartphones and social media. Psychologist Jean Twenge found dramatic shifts in teen behavior starting in 2012, the first year the majority of Americans owned smartphones.

Biz pushes back against the premise that social media increases anxiety, saying it’s an outlet for self-expression and connecting with others with similar interests. “I run a poetry account [on Instagram] and that makes me really happy all the time.”

For Biz, world issues such as global warming, homophobia, and racism cause more anxiety than social media. “It’s stressful to know you’re going to have to be the change,” if change is going to happen on such issues, she says.

While teens from all demographics face anxiety in themselves or peers, it’s important not to lump everyone together, says Angela Neal-Barnett, a professor at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio, and director of the university’s Program for Research on Anxiety Disorders among African-Americans.

“We have to be honest and talk about race and racism, particularly structural racism,” she says. “The research is clear that for black Americans, anxiety is more intense and tends to be more chronic,” especially as black teens experience the recurrence of troubling news reports, such as the shootings of unarmed black men.

Tell teens: This isn’t permanent

On a recent chilly evening in Groton, Massachusetts, about 100 people gathered in the local middle school to hear Lynn Lyons, a psychotherapist from Concord, New Hampshire, talk about breaking the cycle of anxiety.

Ms. Lyons cracks jokes on stage as she covers topics ranging from how to prevent and treat anxiety, to how parents can rein in their own anxiety.

In an interview before her talk, Ms. Lyons says it’s key for teenagers to know the feelings they have now aren’t permanent.

“When we use the language of permanence with teenagers, like ‘you have this condition called anxiety’ or ‘you have this disease called depression,’ we are basically saying to them, ‘you will be like this forever,’ ” she says. “That’s the exact opposite message that we want to give teens who are struggling.”