'Behind the Photos' series re-frames the way we see photographers

Loading...

In a world of digital photography and instant Snapchat gratification, commercial photographer Tim Mantoani’s new “Behind the Photos” series exposes viewers to the people responsible for some of the most iconic images ever taken.

“It’s important for people to remember there’s a photographer taking these pictures, not just a camera,” Mr. Mantoani says in a phone interview from his studio in San Francisco, Calif. “The image of The Afghan Girl [Sharbat Gula] in Peshawar, Pakistan from 1984 didn’t just happen to Steve McCurry. He looked for her for 17 years and finally found her in 2002. Great images don’t just fall into your lap. These photographers are incredibly dedicated. They’re out there for years searching until they find that one image to make available, accessible, to all of us.”

Mantoani says that in 2006, after a year of shooting only digital images, he longed for the complexity and thoughtfulness that goes into shooting 35-millimeter and other classic film exposures.

“I remembered that a long time ago, Kodak company made some of these mammoth Polaroid cameras that were a 20×24 Polaroid camera and they then invited all these artists, like Warhol, to come and use them,” Mantoani says. “At that time, in 2006, I was seeing the writing on the wall for camera companies as digital was making everyone into a ‘photographer.’ So I wanted to use one of these legendary cameras while I still could.”

The Polaroid 20×24 is an instant camera that produces plates of 20 inches by 24 inches (approximately 50cm x 60cm). The camera weighs 235 pounds and has its own custom wheeled tripod in the form of an old barber’s chair, he explains.

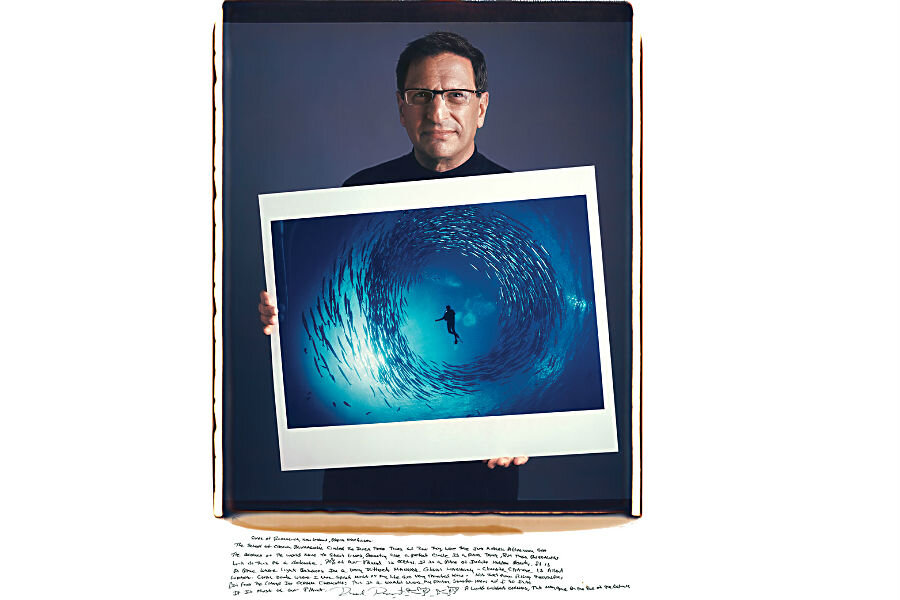

He decided to, in a way, reinvent the term 'double-exposure' by shooting portraits of famous photographer holding their most iconic work.

“Because the photos cost about 75 bucks an exposure, I called Jim Marshall [known for his iconic music industry images] and asked him to come and pose holding one of his photos. That’s where it began and it just grew from there as I began to network with my subjects,” Mantoani says.

The photographer explains that his initial goal was simply to use the old technology before it was inaccessible and in the process access the deep bond between a photographer and the process of creating a very moving and important image.

“We’re losing both process and people right now,” he says. “It’s kind of a twin disappearing act.”

Because of the new technology, camera phones and social media we’re “losing process,” Mantoani explains. “Being a photographer back in the days before digital ... meant planning, being very selective because you only had maybe a couple of rolls of film you could afford to buy and develop so you waited, searched for the image and were dedicated. For some of these people, it took years to get the shot.”

Mantoani ads that the access once granted to photographers has all but vanished. Part of the “process" meant that most of the iconic images were not staged, but spontaneous moments captured by a patient, intuitive, ever-present and dedicated professionals.

“The images of Elvis and the Beatles that some of these people captured aren’t going to happen again because today publicists and handlers would never allow you to come into the bathroom to watch them shave or stand in the wings and see them kiss a girl,” he says.

The more photographers he captured with their work, the greater the network and enthusiasm for Mantoani's project became. He would ask each of his subjects to hand write a little note about their iconic image at the bottom of the newly shot, monster Polaroids.

Harry Benson wrote across the bottom of his famous picture of the Beatles engaging in a moment of pure, pillow fight abandon: “Brian Epstein – Beatles Manager – had just told them they were number one in America – and I was coming with them to New York. 1964”

Nick Ut wrote simply, “June 8, 1972 Trang Bang Village Kim Phuc 9 year-old girl South Vietnam drop napalm in her village.”

“People ask me how I chose my subjects and I say ‘They chose me,’” says Mantoani. “Photographers would put me in touch with other famous photographers. So it grew to the point where I ended up with more than 150 other photographers and the photos that made them famous.”

The portrait series is available in book form on Amazon.