The neoliberal consensus is crumbling. What happens next?

Loading...

Neoliberalism, the dominant narrative guiding Western democracies and their economies for almost 70 years, is crumbling all around us.

It was set up to protect our freedoms. But neoliberalism's excesses and failures – from recent financial crises to soaring levels of income inequality – have fueled populist movements that threaten not only open markets and free trade but the very freedoms it was meant to safeguard.

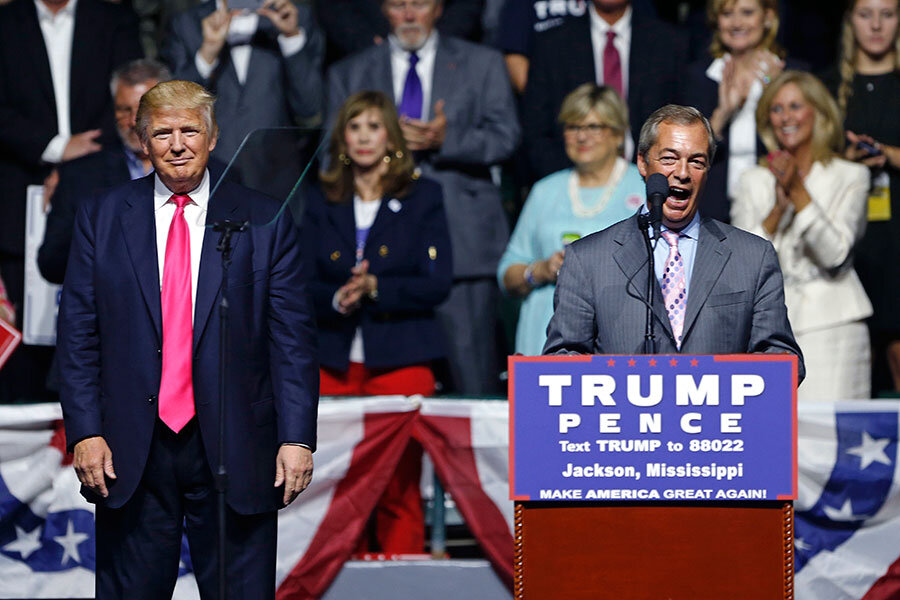

The U.K.'s vote for Brexit, the U.S. election of Donald Trump and the rise of both right- and left-wing populism across Europe all point to a desire for change from the established order and a more equitable distribution of the world's wealth. But in each case the popularly chosen remedy is worse than the disease it's intended to cure.

Neoliberalism emerged from the ashes of World World II when a group of economists, politicians, philosophers and others gathered at a ski resort in Switzerland convinced that more open markets would help protect the freedoms threatened by fascism.

With those ideas now discredited, and fascism once again on the rise, it's past time to devise a new narrative to guide our economies in a way that prevents neoliberalism's excesses, promotes universal well-being as an economic imperative and ensures nationalism doesn't once again win the battle of ideas.

While a narrative may not seem like much, my research suggests how important such narratives and their underlying "memes" are in fostering the kind of system change we need right now.

The old narrative

Ask any business or economics student what the purpose of a company is. Most likely you will get the same answer: to maximize shareholder wealth.

This narrow view is deeply embedded in the thinking of business school professors and economists and, as a result, of the manager-wannabes they teach.

Yet it is highly problematic, since there are many other groups besides investors whose contributions to the business are as necessary and valuable. Think employees, customers, communities and suppliers, to name a few. Even General Electric's former CEO Jack Welch, the one-time "father" of shareholder wealth maximization, claimed in 2009 that it was "the dumbest idea in the world."

Yet shareholder wealth maximization still dominates economic thinking, and it is a direct result of those neoliberal ideas that emerged from that Swiss mountainside.

How the old narrative was made

The perspective that companies exist to maximize shareholder wealth is most often attributed to now-deceased economist Milton Friedman. Friedman's arguments, embedded in virtually all economics textbooks, derive from the work of a relatively little-known group of economists, philosophers and historians.

This group, including Friedman, met at Mont Pelerin, Switzerland in 1947 to grapple with the expansion of government interventions they claimed threatened freedom, dignity and particularly free enterprise. They developed the narrative we know as neoliberalism or neoclassical economics. This narrative now dominates global understanding of what economies and businesses do and why they exist, not to mention the nightly news (via constant markets coverage).

The Mont Pelerin Society, whose members included economist Friedrich von Hayek, philosopher Karl Popper and economist George Stigler, agreed on a few core ideas and then crafted them into a resonant story about the purpose of business and how economies – and, ultimately, the world – ought to work.

They acted individually in their own countries to foster freedom and private rights, uphold the functioning of markets and create a globalized order that safeguarded peace and liberty. Some went on to hold positions of power and others had great influence over those who wielded it, such as President Ronald Reagan and U.K. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who embraced Friedman's ideas and ushered in the "maximize shareholder wealth" era for companies.

The result of the Mont Pelerin Society's work is a set of familiar memes, or core units of culture.

Memes and markets

Unlike internet memes, which spread via the worldwide web, the memes I'm talking about refer to ideas, phrases, symbols and images that replicate from person to person when they resonate, and are ubiquitous. Our common understandings, belief systems and the stories that we tell ourselves about how the world works are based on such memes.

Memes are, I recently argued, an overlooked and vitally important aspect of system change. Recognizable memes form the basis of today's dominant economic narrative: free markets, free trade and globalization, private property, competition, individual but not shared responsibility, and maximization of company and shareholder wealth.

The success of these memes speaks to why business students so readily identify the purpose of the business as maximizing shareholder wealth and with the language of free markets and trade. They are simple, identifiable and based on laudable values like freedom and individual responsibility, after all: things that Americans in particular, with their individualistic orientation, can readily identify with.

Their power to convey the underlying economic "story" illustrates why change that seems to astute observers to be necessary – change toward more sustainability, dealing with climate change and fostering greater equity – is so difficult. Neoliberalism's pursuit of endless growth, efficiency and free trade have led to setbacks in curbing climate change, enhancing sustainability and reducing inequality, all of which are potentially existential crises for humanity.

In other words, those changes don't fit neatly into market logic because they include both social and ecological values in addition to economic ones. Thus, neoliberalism can't absorb them. Successful memes resonate broadly and are difficult to change unless other, equally successful ones replace them.

Such complex and "wicked problems" are difficult to resolve because there are just too many groups and individuals with different ideas about what the problem is and what caused it, and how to best deal with it.

How to bring about system change

Recent work with colleagues on how to bring about large system change to cope with such problems suggests that there is really no way to plan or control such change.

What is needed, as happened with the creation of neoliberalism's core narrative, is that a new set of memes framing a new economic and societal narrative needs to be established. An emerging group called Leading for Wellbeing and composed of global organizations, universities and newspapers is attempting to do just this, built on the notion that the world's major institutions and businesses should "operate in service of well-being and dignity for all."

Tomorrow's narrative needs to be framed very differently from today's. It needs to recognize that economies are part of societies and nature but not the only important thing. A new narrative should frame the purpose of business very differently, taking different stakeholders and the natural environment into account. It could also provide a more reasonable and effective basis for resolving the key crises of our time, such as the warming planet and the growing gap between rich and poor.

Companies could, as business professors Tom Donaldson and Jim Walsh recently argued, focus on producing collective value, rather than simply shareholder wealth.

Dignity and well-being can be enhanced, for instance, by emphasizing job creation and stability, fair wages and fair markets, rather than financial wealth, efficiency and growth. Measures like the Genuine Progress Indicator would incorporate well-being and individual dignity into the measure of an economy, as opposed to merely its activity, making it a great substitute for GDP or GNP.

If we hope to overcome this tide of populism and nationalism sweeping the West, a new, more powerful narrative is desperately needed – a new story that proves more compelling than the one that brought Trump and populists in Europe to power.

Sandra Waddock, Galligan Chair of Strategy and Carroll School Scholar of Corporate Responsibility, Boston College

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.