Congress asks: Do Amazon, Facebook, Google, Apple play fair?

Loading...

| Washington

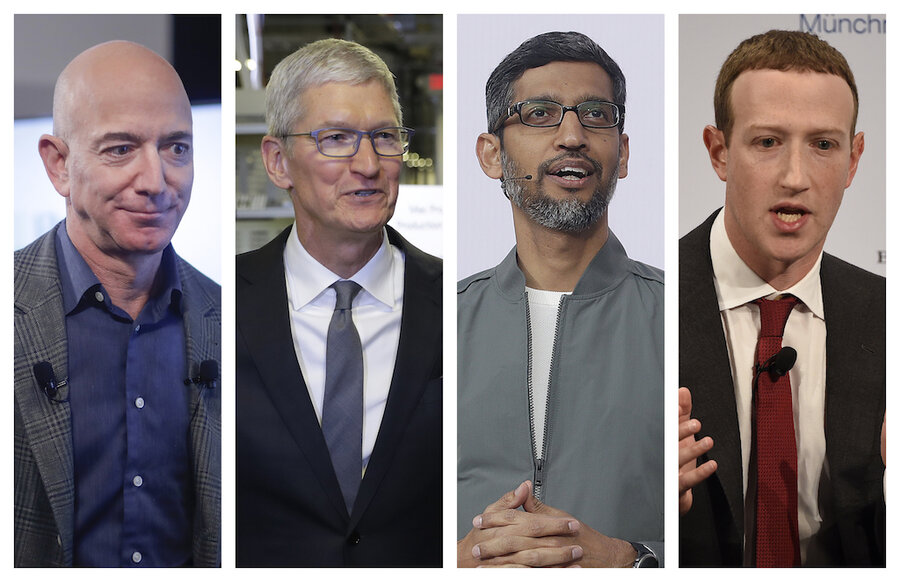

Four Big Tech CEOs – Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg, Amazon's Jeff Bezos, Sundar Pichai of Google, and Tim Cook of Apple – are set to answer for their companies' practices before Congress as a House panel caps its yearlong investigation of market dominance in the industry.

The four command corporations with gold-plated brands, millions or even billions of customers, and a combined value greater than the entire German economy. One of them is the world's richest individual (Mr. Bezos); another is the fourth-ranked billionaire (Mr. Zuckerberg). Their industry has transformed society, linked people around the globe, mined, and commercialized users' personal data, and infuriated critics on both the left and right over speech.

Critics question whether the companies, grown increasingly powerful after gobbling up scores of rivals, stifle competition and innovation, raise prices for consumers, and pose a danger to society.

The four CEOs are testifying remotely for a hearing Wednesday by the House Judiciary subcommittee on antitrust.

In its bipartisan investigation, the panel collected testimony from mid-level executives of the four firms, competitors, and legal experts, and pored over more than a million internal documents from the companies. A key question: whether existing competition policies and century-old antitrust laws are adequate for overseeing the tech giants, or if new legislation and enforcement funding is needed.

Subcommittee chairman Rep. David Cicilline, a Rhode Island Democrat, has called the four companies monopolies, although he says breaking them up should be a last resort. While forced breakups may appear unlikely, the wide scrutiny of Big Tech points toward possible new restrictions on its power.

The companies face legal and political offensives on multiplying fronts, from Congress, the Trump administration, federal and state regulators, and European watchdogs. The Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission have been investigating the four companies' practices.

Each company has a distinct profile and sets its widening footprint in specific markets, and each tech titan has his own approach and story to tell.

For Mr. Bezos, who presides over an e-commerce empire and ventures in cloud computing, personal "smart" tech, and beyond, it will be his first-ever appearance before Congress.

Mr. Bezos is introducing himself, in a way, in his hearing testimony, unusual for the occasion. He lays out his challenging life story growing up in New Mexico as the son of a single mother in high school, and later with an adoptive father who emigrated from Cuba at 16. Previewing his written testimony in a blog post Tuesday, Mr. Bezos traces his origins as a "garage inventor" who came up with the concept of an online bookstore in 1994.

He addresses the issue of Amazon's power in what he describes as a huge and competitive global retail market. The company accounts for less than 4% of retail in the United States, Mr. Bezos maintains. He affirms his rebuff to critics who call for the company to be broken up: Walmart is more than twice Amazon's size, he says.

Mr. Bezos initially declined to testify unless he could appear with the other CEOs. He'll likely face questioning over a Wall Street Journal report that found Amazon employees used confidential data collected from sellers on its online marketplace to develop competing products. At a previous hearing, an Amazon executive denied such accusation.

In the wake of George Floyd's death and protests against racial injustice, Facebook's handling of hate speech has recently drawn more fire than issues of competition and privacy, especially after Facebook's refusal to take action on inflammatory Trump posts that spread misinformation about voting by mail and, critics said, encouraged violence against protesters.

Mr. Zuckerberg has said the company aims to allow as much free expression as possible unless it causes imminent risk of specific harms or damage. "We believe in values – democracy, competition, inclusion, and free expression – that the American economy was built on," he says in his testimony prepared for the hearing.

"I understand that people have concerns about the size and perceived power that tech companies have," Mr. Zuckerberg's statement says. "Ultimately, I believe companies shouldn't be making so many judgments about important issues like harmful content, privacy, and election integrity on their own. That's why I've called for a more active role for governments and regulators, and updated rules for the internet."

European regulators have concluded that Google manipulated its search engine to gain an unfair advantage over other online shopping sites in the e-commerce market, and fined Google, whose parent is Alphabet Inc., a record $2.7 billion. Google has disputed the findings and is appealing.

Attorneys general from both parties in 50 states and territories, led by Texas, launched an antitrust investigation of Google in September, focused on its online advertising business.

"Google operates in highly competitive and dynamic global markets, in which prices are free or falling, and products are constantly improving," Mr. Pichai says in his written testimony. "Competition in ads – from Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, Comcast, and others – has helped lower online advertising costs by 40% over the last 10 years, with these savings passed down to consumers through lower prices."

Apple, whose iPhone is the third-largest seller in the world, faces EU investigations over the fees charged by its App Store and technical limitations that allegedly shut out competitors to Apple Pay.

"Apple does not have a dominant market share in any market where we do business," Mr. Cook says.

He is making the case that the fees Apple charges apps to sell services and other goods are reasonable, especially compared with what other tech companies collect. In over a decade since the App Store launched, "we have never raised the commission or added a single fee," Mr. Cook says in his testimony.

This story was reported by The Associated Press.

Editor’s note: As a public service, the Monitor has removed the paywall for all our coronavirus coverage. It’s free.