Can old-fashioned journalism combat fake news?

Loading...

Fiction masquerading as news has persisted since the early days of the printing press. But the ease of publication in the Digital Age has made it all the more difficult for readers to sort reported, objective journalism from the chaff of hoaxers and propagandists.

Recent years have seen attempts to draw political maps of the media landscape, but efforts to alert readers to bias are susceptible to internal biases as well. Bias, however, is different from outright misinformation. To help people distinguish the genuine from the ersatz, journalist, lawyer, and entrepreneur Steven Brill teamed up with former Wall Street Journal publisher Gordon Crovitz to create NewsGuard, a company that has so far produced “nutrition labels” for 2,200 sites.

NewsGuard’s methodology is a decidedly old-school approach to a new problem. Instead of using algorithms or other machine-learning tools, NewsGuard has paid dozens of journalists to dig into each site and to contact news organizations for comment. Some critics caution that the effort borders on censorship, while others describe the effort as “sensible” and a “valuable service.”

Why We Wrote This

The prevalence of misinformation on the internet is legitimately troubling, but could attempts to remedy the problem fall prey to all-too-human biases?

Google “What is fracking?” and one of the top results will be what-is-fracking.com, a cleanly designed website that explains that extracting natural gas through hydraulic fracturing does not contaminate drinking water, does not pollute the air to a significant degree, and helps raise wages in local communities.

What the site doesn’t explain is who published it. The only hint is a copyright notice, in 10.5-point font at the bottom of each page, linking to “api.org.”

“I don't care what you think of fracking,” says journalist, lawyer, and entrepreneur Steven Brill. But, he says,“you should know that this website, which reads like The Economist, is owned and operated and published by the American Petroleum Institute.”

Why We Wrote This

The prevalence of misinformation on the internet is legitimately troubling, but could attempts to remedy the problem fall prey to all-too-human biases?

Whether created by spammers, grifters, conspiracy theorists, or propagandists, sites that conceal or play down their ownership and financing, blend news with advertising, and routinely publish misinformation are widespread on the internet. And it’s not always easy to distinguish these sites from the ones operated by those acting in good faith.

“There are so many sites now that it’s hard to know which ones are credible and aren’t credible,” says Lisa Fazio, a psychologist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville who studies how people process information. “It takes a lot of effort and cognitive brainpower to really think through our prior knowledge on a topic, so we tend not to do that.”

Fake news is, of course, nothing new, nor is the feeling that misinformation is prevailing. Outright lies and misleading narratives masquerading as facts have persisted since the early days of the printing press. But the ease of publication in the Digital Age has made it all the more difficult for readers to sort reported, objective journalism from the chaff of hoaxers and propagandists.

Recent years have seen attempts to draw political maps of the media landscape, but efforts to alert readers to bias are susceptible to internal biases as well. For instance, AllSides, a news aggregator that presents news from across the political spectrum, labels MSNBC, the television network that in 2003 canceled Phil Donahue’s show for being too liberal, as being on the far left. It places Newsmax, a conservative news site that in 2009 laid out how a military coup could be the “last resort to resolve the ‘Obama problem,’ ” in an equivalent position on the right.

Other efforts to map media bias fail to capture the political stances of the publications they rate. For instance, the popular “Media Bias Chart” created by Ad Fontes Media places the liberal-leaning online news magazine Slate to the left of the unabashedly progressive TV and radio program Democracy Now!, a rating that is laughable to anyone familiar with both news outlets.

Ordinary people are, on average, good at identifying media bias, says Gordon Pennycook, a psychologist at the University of Regina in Saskatchewan, Canada. His research, published last month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found that non-experts across the political spectrum tended to rate mainstream news outlets more trustworthy than low-quality or hyperpartisan sources.

“But,” he says, “they aren't so good at determining the quality of mainstream sources.”

Other efforts to rate the credibility of news outlets rely on machine learning. In 2016, Google gave more than $170,000 to three British firms to develop automated fact-checking software.

An old-school approach

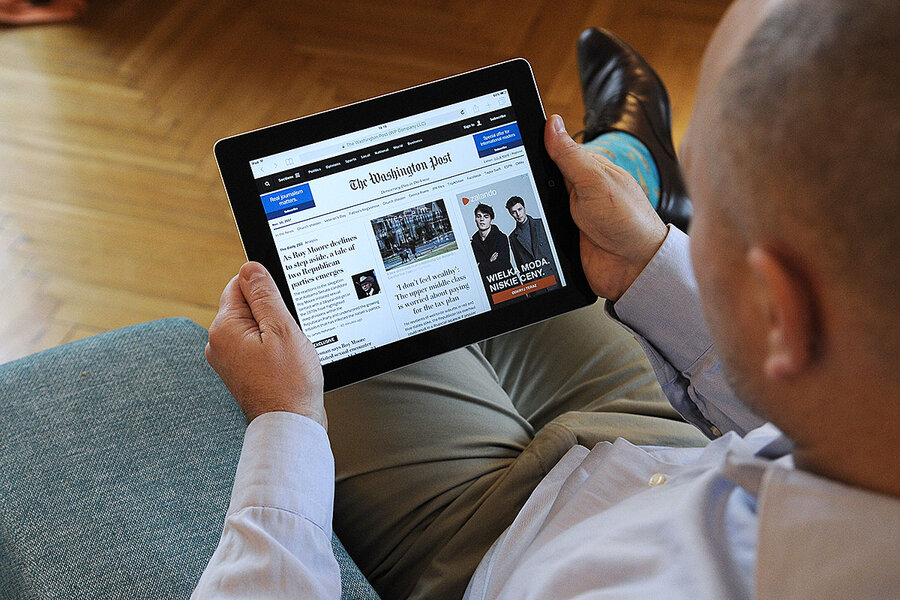

To help people distinguish the genuine from the ersatz, Mr. Brill and former Wall Street Journal publisher Gordon Crovitz created NewsGuard, a company that has so far produced “nutrition labels” for 2,200 sites, which Brill says account for more than 96 percent of the online news content that Americans see and share. In January Microsoft’s Edge browser included NewsGuard’s technology on mobile browser (Edge users can turn it on in Settings). Desktop users running Chrome, Firefox, and other browsers can install NewsGuard as a plugin.

NewsGuard’s methodology is a decidedly old-school approach to a new problem. Instead of using algorithms or other machine-learning tools, NewsGuard has paid dozens of journalists to dig into each site and to contact news organizations for comment. The nutrition labels, which detail each site’s ownership, history, advertising policies, and editorial stance, can run more than a thousand words.

“When we started talking to tech companies about it, they were horrified at how inefficient it is,” says Brill. “It's actually highly efficient and is the only way to achieve scale.”

Users with the NewsGuard extension will see a badge appearing on their browser toolbar and next to some hyperlinks – a green one with a checkmark for sites rated as credible, a red one with an exclamation point for those rated as not, and a yellow Thalia mask for satire sites like The Onion and ClickHole. Click on a badge, and you’ll see how NewsGuard rates the site according to nine criteria, including objective measures like whether it clearly labels advertising or provides biographies or contact information for the writers, as well as more subjective ones like “gathers and presents information responsibly.”

NewsGuard awards full marks to mainstream news sites like The New York Times, CNN, and The Washington Post. (The Christian Science Monitor also gets top grades.) Far-right sites like Breitbart and InfoWars get failing grades. Not surprisingly, what-is-fracking.com also gets a red badge.

Human-powered, with human biases

NewsGuard’s rating system occasionally produces results that have raised eyebrows. Al Jazeera, the Qatari state-funded news outlet credited with helping to spread the 2010-11 Arab Spring protests, gets a failing grade for not disclosing its ownership and for painting Qatar in a favorable light. Boing Boing, a 30-year-old webzine generally held in high regard by tech journalists, is also tagged as unreliable for blurring the lines between news, opinion, and advertising, claims that Boing Boing’s editors have disputed.

Because it’s powered by human beings, NewsGuard can fall prey to the same human biases that afflict news organizations. For instance, NewsGuard’s label for The New York Times includes a discussion of the 2003 Jayson Blair scandal and the discredited reporting in 1931 by Stalin apologist Walter Duranty, but it contains no mention of the paper’s reporting before the US-led invasion of Iraq, in which the Times, by its own admission, was insufficiently critical in accepting official claims about weapons of mass destruction.

When asked why no mention of the pre-invasion reporting was on the label, Brill said, “It should be there; it will end up there.”

Adam Johnson, an analyst for the nonprofit media watchdog Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, says that NewsGuard fails to account for how mainstream news outlets can manufacture false narratives.

“If any other country used a fake-news plugin to flag false information,” he continues, “we would call it what it is: censorship.”

Brill acknowledges that NewsGuard’s isn’t a panacea. “We are not solving all the problems of the world,” he says. “If we existed in the run-up to the Iraq war, you would not have seen a red mark” on the Times’s reporting on WMDs.

But, he says, his company offers an improvement over how social networks like Facebook and news aggregators like Google News determine which news sites are credible. Those companies keep their process secret, they say, so that people won’t be able to game their system.

“We love it when people game our system,” says Brill. “We now have 466 examples of websites that have changed something about what they do in order to get a higher score.”

“To me [NewsGuard] sounds very sensible,” says Professor Pennycook. But, he says, “the people who are going to go out of their way to install this thing, they’re not the people we’re worrying about.”

NewsGuard’s labels may represent a less heavy-handed way of dealing with misinformation than what some Silicon Valley companies have proposed. In 2017, for instance, Eric Schmidt, the executive chairman of Alphabet, Google’s parent company, said that it should be possible for Google’s algorithms to detect misinformation and delist or de-prioritize it on search-engine results pages, an approach that Mr. Johnson calls “creepy and dystopian.”

“I don’t really believe in de-prioritizing,” says Brill, who says he would be uncomfortable licensing his technology to companies that would hide sites flagged as unreliable. “Our view is that people ought to have the chance to see everything.”

Still, NewsGuard’s ranking system, if widely adopted, would likely influence whether people choose to read or share certain stories. In a Gallup poll commissioned by NewsGuard, more than 60 percent of respondents said they were less likely to share stories from sites that were labeled as unreliable.

It’s this binary approach to news that rankles Johnson. “People aren’t children,” he says. “They should be able to navigate information online without a US corporate, billionaire-funded report card telling them what’s real or not.”

Robert Matney, the director of communications for New Knowledge, an Austin-based cybersecurity company that the US Senate commissioned to investigate Russia’s efforts to influence US politics, notes that the strength of companies like NewsGuard lies not necessarily in their ratings, but in the way they educate the public.

“Encouraging news/media literacy by enabling consumers to learn more about sources is a valuable service,” he writes via email.