How '5-D' glass discs can store data for billions of years

Loading...

The library of Alexandria stood for hundreds of years before its manuscripts were burned in successive acts of destruction. Information stored on CDs and DVDs can last for up to 200 years before bit errors make the discs unreadable. Even the golden records aboard the Voyager spacecraft, containing images, words, and music representing human culture, will be gradually erased by micrometeoroid impacts over hundreds of millions of years.

Preserving culture and knowledge over the very long term is a tricky problem, and one that has generally been solved by moving information from one medium to another: from paper to optical discs, from optical discs to the cloud. But now, researchers at the University of Southampton’s Optoelectronics Research Centre say they’ve come up with a way to store information eternally.

The technique involves encoding information into glass discs using a high-speed laser. Glass is a tough and chemically stable material, and if the discs are stored in a stable environment the information contained in them should last up to 13.8 billion years – more than three times the age of the Earth. Even if the discs are not stored in a stable environment, they can withstand temperatures of up to 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit.

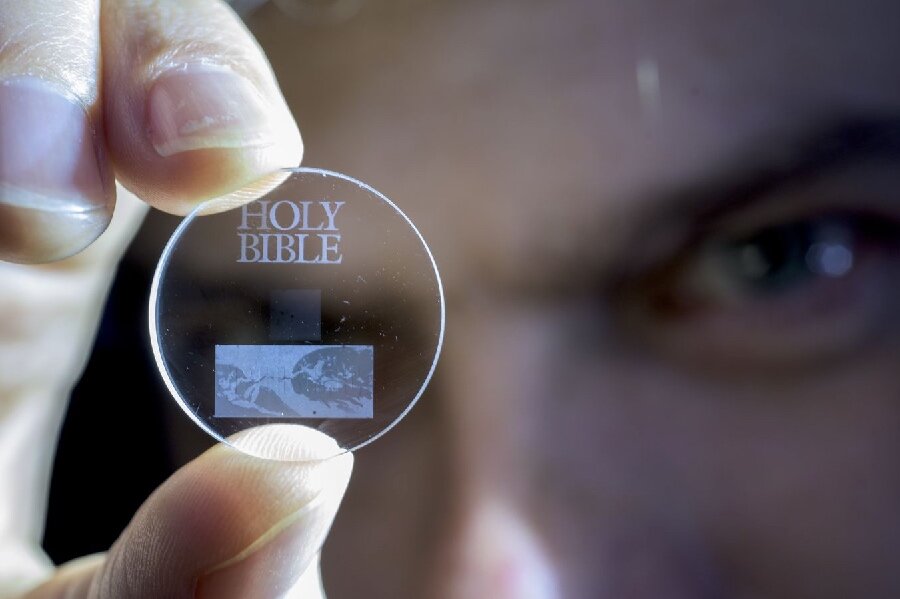

The encoding technique uses a laser to etch information into “nanogratings” embedded in glass wafers about an inch across. These tiny structures refract light, much as a CD does as a laser reads the information on its surface. But instead of storing information in only two dimensions (1s and 0s), the nanogratings store information in five dimensions: the orientation and size of the gratings as well as their three-dimensional position on the disc. Each glass disc can store up to 360 terabytes of data, the equivalent of almost half a million CDs.

The research team has encoded the King James Bible, the Magna Carta, Isaac Newton’s book Opticks, and the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights into the new format, as a way of demonstrating its utility for preserving human knowledge and culture.

“We have created the technology to preserve documents and information and store it in space for future generations,” said University of Southampton professor Peter Kazansky in a statement. “This technology can secure the last evidence of our civilisation: all we’ve learnt will not be forgotten.”

Of course, storing data is only part of the problem: even if the glass discs survive for thousands, millions, or even billions of years, they have to be readable by whoever finds them.

A commercial reader for 5-D glass discs could be developed within a few decades, a member of the research team told The Verge’s James Vincent, but that technology certainly will not survive as long as the discs themselves. In acknowledgement of this difficulty, the discs are etched with designs – the King James Bible, for example, carries a small reproduction of Michelangelo's Creation of Adam fresco – so that future generations may at least have a clue that the discs contain significant information.