Can MIT researchers save the incandescent lightbulb?

Loading...

The incandescent lightbulb may be gearing up for a come back.

After more than a century of household dominance, in recent years, Joseph Swan's high-watt, incandescent lights seemed to be heading the way of transistor radios and rotary phones, ousted from public favor by newer, more efficient designs. But thanks to researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Purdue University, the lowly incandescent bulb is getting a jolt of new life.

The six-researcher team says it has found a way to boost the bulb's efficiency twenty-fold, which would leave today's favored compact fluorescents (CFLs) and light-emitting diodes (LEDs) in the dust, according to a paper published Monday in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

"We are very excited about the potential" to build a better lightbulb, MIT physics professor, Marin Soljačić, told the BBC.

Traditional incandescent bulbs lose huge amounts of energy: less than 5 percent of the energy given off when they're heated up by electrical wire, to temperatures nearly 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit, actually creates light. The rest creates heat. Although that's useful in some devices, like incubators, scientists have attempted to channel it back towards a brighter bulb.

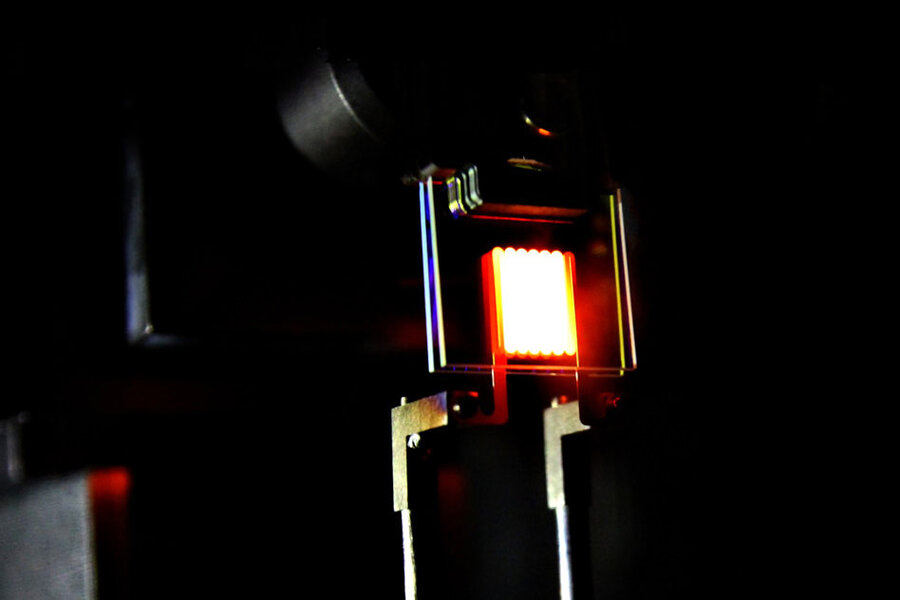

In the past, researchers have tried to tinker with objects' thermal emission spectrum, but had difficulty adjusting spectra at very high temperatures. The MIT team is the first to crack that problem, building photonic crystals that help capture the infared radiation that would otherwise escape as heat. Instead, it bounces back to the filament: reflecting, reabsorbing, and re-emitting until it produces light we can see. Nothing invisible escapes.

The result is a light source "surpassing existing lighting technologies, and nearing a limit for lighting applications," the researchers write, "with exceptional reproduction of colours and scalable power" compared to CFLs and LEDs.

The two-stage "light recycling" process creates a luminous efficiency of up to 40 percent, versus 2-3 percent for regular incandescent lightbulbs. Even today's greener alternative bulbs only reach 15 percent. Actual samples produced by researchers only reached 6.6 percent, but that's still a huge improvement over the norm.

The thinly-layered photonic crystals, which reflect back otherwise unusable infared wavelengths, are made of easily-sourced materials, another reason researchers believe it could be applied to create more efficient incandescent lightbulbs. And Dr. Soljačić is optimistic that similar applications could improve other technologies, like thermo-photovoltaic devices, which take external heat, make it glow, and then convert that light into electricity.

Figuring out how to control thermal emissions is "the real contribution of this work," Soljačić said in an MIT press release, and he cautions that people should keep buying low-energy lighting, like LEDs, to combat global warming. But better bulbs could be ahead.

"Thomas Edison was not the first one to work on the design of the lightbulb, but what he did was figure out how to mass produce it cheaply and keep it stable longer than 10 hours ... These are the questions we are trying to answer now," he told the BBC.