‘It smells like gunpowder’: Astronauts tell of their time on the moon (audio)

Loading...

What happens on the moon ... winds up in the NASA archives forever.

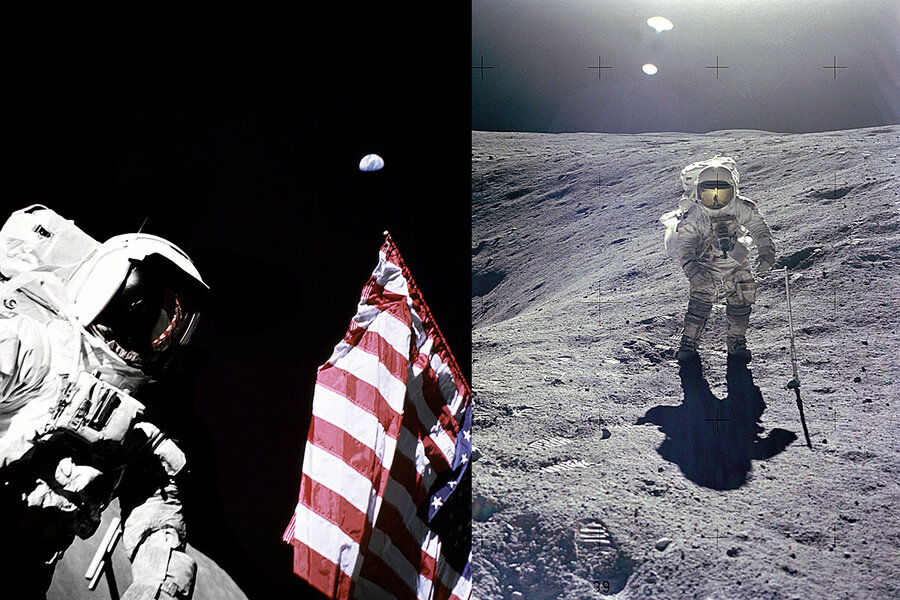

From astronauts joking about losing the keys to the spaceship and calling each other “twinkle toes” to merrily singing as they float above the moon dust, footage from the Apollo-era moonwalks has immortalized the magic of those once-in-a-lifetime experiences.

Monitor science reporter Eva Botkin-Kowacki had a chance to ask two of those national heroes directly about what that experience has meant to them. Charlie Duke was in mission control when Apollo 11 landed on July 20, 1969. He got the chance to go himself three years later. Harrison “Jack” Schmitt was one of the last two men to walk on the surface of the moon.

Why We Wrote This

The moon landing may have been a shared experience for all of humanity, but in actuality only 12 people have set foot on the moon. Our reporter got to meet two of them. Hear them for yourself in this audio story.

“Imagine being in a valley as deep as this one,” Dr. Schmitt says, “with a brilliant sun, a blacker than black sky, and the Earth hanging over the southwest wall of the mountain – always in the same place.”

Hear their stories firsthand in this audio story:

AUDIO STORY TRANSCRIPT:

EUGENE CERNAN [NASA ARCHIVAL AUDIO]: Hey Jack, don’t lock it.

HARRISON “JACK” SCHMITT [NASA ARCHIVAL AUDIO]: I’m not going to lock it.

CERNAN [NASA ARCHIVAL AUDIO]: We've got to go back there. If you lose the keys, we’re in trouble.

JACK [NASA ARCHIVAL AUDIO]: Hey, who’s been tracking up my lunar surface?

CERNAN [NASA ARCHIVAL AUDIO]: OK? Just walk around for one second.

JACK [NASA ARCHIVAL AUDIO]: Woo hoo.

CERNAN [NASA ARCHIVAL AUDIO]: You’re pretty agile there, twinkle toes.

JACK [NASA ARCHIVAL AUDIO]: You bet your life I am.

EVA BOTKIN-KOWACKI: That was Apollo 17 mission commander Eugene Cernan, talking to astronaut Harrison Schmitt during their first moonwalk, in 1972. In all of human history, just 12 people have landed on the moon. Only four of them are still alive. I’m Monitor science reporter Eva Botkin-Kowacki, and last month I had the privilege of interviewing two of them: Harrison Schmitt, who goes by Jack, from the Apollo 17 mission, and Apollo 16’s Charlie Duke. I’ve read about their missions in history books. I’ve seen grainy images. And I’ve looked up at the moon at night. But I never could quite picture what being there would be like. Then, I talked to Jack.

JACK: Imagine being in a valley as deep as this one, with a brilliant sun, a blacker than black sky, and the Earth hanging over the southwest wall of the mountain – always in the same place. Once we took our helmets off, you could smell the lunar dust.

EVA: In the module?

JACK: In the module.

EVA: Really? What did it smell like?

JACK: And it smells like gunpowder – everybody said the same thing. It smells like activated carbon.

EVA: Only 12 people have experienced that firsthand. They belong to one of the most exclusive clubs on Earth. They trained intensely together for years leading up to their missions, and many even lived in the same suburban neighborhood in Houston.

CHARLIE DUKE: The whole neighborhood was going to the moon. Literally!

EVA: That’s Charlie talking.

CHARLIE: Where we lived our next-door neighbor was Bill Anders. Neil Armstrong was a block behind us. Tom Stafford lived in the neighborhood. Frank Borman lived in the neighborhood too. Steve Russo lived in the neighborhood. Ron Evans lived – I could go on and on and on and on. My kids never said this but it was, “When are you going to go, Dad?” They knew I was going to go but they were really young and so to get them involved I took a picture of my family and left it up on the moon. I don’t know whether you’ve seen that picture?

EVA: I think I have.

CHARLIE: But it was really exciting for them. They’re going to be on the moon with Dad.

EVA: Charlie went to the moon on the Apollo 16 mission in April 1972. But you might recognize his Southern drawl if you’ve heard recordings from the first moon landing – the Apollo 11 mission. Four voices marked that historic moment for the public: astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, anchorman Walter Cronkite, and Charlie, who was the voice from mission control. Give a listen to when Apollo 11 touched down on the moon on July 20, 1969.

NEIL ARMSTRONG [NASA ARCHIVAL AUDIO]: Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed!

HOUSTON (CHARLIE) [NASA ARCHIVAL AUDIO]: Roger, Twang – Tranquillity. We copy you on the ground. You’ve got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.

CHARLIE: I probably was more nervous in mission control on Apollo 11 than I was when we landed on the moon.

EVA: Still, you can hear Charlie’s excitement when he did land on the moon.

CHARLIE [NASA ARCHIVAL AUDIO]: Old Orion is finally here, Houston, fantastic! Yahoo golly, this is so pretty you won’t believe it.

HOUSTON [NASA ARCHIVAL AUDIO]: I believe it, Charlie.

EVA: The astronauts weren’t at all what I expected. These men had done the impossible. But they weren’t swaggering or arrogant, they were kind, and even warm. When I introduced myself to Jack, he asked me a kind of peculiar question – how to spell my name. I told him: E-V-A. He chuckled. E-V-A stands for “Extravehicular activity.” So to Apollo astronauts my name is code for a moonwalk.

JACK: We waited until Mission Control looked at all the systems and felt like there was no reason not to have an excursion. An E-V-A.

EVA: Kidding aside, getting to the moon was serious business.

JACK: You have to stay focused. You can’t “gee whiz” and end up crashing on the moon.

EVA: So is there any moment of gee whiz?

JACK: Well the whole mission was gee whiz!

EVA: Well, gee whiz, and insanely dangerous. Pretty much everything they did could’ve gone horribly wrong. Take liftoff. The crew rode in a little, tiny capsule atop a massive, fiery rocket. The spacecraft smashed through our planet’s atmosphere before ditching the launch rocket and heading to the moon.The astronauts then had to land their tiny craft very, very carefully. Each mission went to a site that had never before been seen up close. So, there might’ve been unexpected obstacles. Then there’s actually leaving the spacecraft. Spacesuits are the only things keeping the astronauts alive during a moonwalk.

JACK: Well the sounds outside are sounds of your suit, of the pumps and fans and your own voice when you’re talking and the voices from Houston and your companion. When we were taking cores, driving a core with a hammer, I could feel that through the surface. And that’s sound but that’s not what we’re used to thinking of as sound. It’s a seismic vibration. So no, it’s not silent. Some of my colleagues have talked about the silence of the moon. It ain’t silent. It better not be or you’re gonna be in trouble.

EVA: Before meeting Jack, I watched a delightful video clip of him walking on the moon. Well not walking – skiing actually. He would glide just above the moon’s surface, pushing off with his toes like he had learned cross-country skiing.

EVA: What does it feel like to be in that low gravity?

JACK: Well, it feels like being on a giant trampoline. I hope everyone’s been on a trampoline before, but just imagine it never stops. There’s no end to it.

EVA: I saw a little clip of you and Cernan hopping along on the moon –

JACK: Yeah, well for some reason the pilots liked to hop and I didn’t find that very efficient.

EVA: You were skiing.

JACK: I was skiing usually, usually.

EVA: In this clip, you guys are singing.

JACK: Well I had a habit in those days of when I heard a line that is part of or similar to a line in a song that I’ll start singing. I would start singing that song. And I think Cernan had said something like, “It’s really something walking on the moon.” And I just started, “I was walking on the moon –”

JACK [NASA ARCHIVAL AUDIO]: I was strolling on the moon one day, in the merry, merry month of December –

CERNAN [NASA ARCHIVAL AUDIO]: No, May –

JACK [NASA ARCHIVAL AUDIO]: May – that’s right.

CERNAN [NASA ARCHIVAL AUDIO]: May is the year of the month.

JACK [NASA ARCHIVAL AUDIO]: When then much to my surprise, a pair of bonny eyes dah doo dah doo

HOUSTON [NASA ARCHIVAL AUDIO]: Sorry about that, guys, but today may be December.

EVA: What is it like to come back home to regular life?

CHARLIE: Of course you’re so excited when you get back, you can’t stop talking about what you’ve seen and what you’ve done. You were so excited still, you say, “I want to go again.” But there was no chance.

EVA: That was Charlie of Apollo 16. He almost had a chance to go back; he was on the backup crew for the final mission – Apollo 17. And would’ve flown to the moon again had something happened to Jack.

CHARLIE: But they stayed healthy. Jack wouldn’t let me close to him. So I didn’t get to break his legs so I could go again, and I’m just teasing of course, but we really supported one another.

EVA: By the way, Jack was about 10 feet away while I was interviewing Charlie.

CHARLIE: But then after Apollo was over, there was a letdown. No question about it. You know that drive that took you there is still inside. You know, how you’re going to channel this. You climbed to the top of the ladder and now what are you going to do with the rest of your life?

EVA: I was chatting with my parents – I’m too young to have been alive when it happened – about that shift in perspective of having people on the moon, and they were, they were talking about how they looked at the moon a little differently because they knew humans had been there and that was such a wild thing to think about. I’m curious for you, coming back was it at all this kind of “I went there.”

CHARLIE: Yeah. You still get that feeling. Sometimes on a full moon, I look up and it’s a feeling of satisfaction that, you know, I got to do that. And so that’s a humbling thought that I got picked. And so when I look up it is just a thank you that I got a chance to have that opportunity. But it’s also still romantic. It’s a nice beautiful moon.

EVA: When I look up at the moon, I wonder what else is out there. Charlie and Jack have been able to probe that mystery in a way that I probably never will. They’ve been to the doorstep of the final frontier. Jack was one of the last two humans to set foot on the moon. Space agencies are sending robotic envoys hurtling through our solar system today. But no human has left Earth-orbit since the end of the Apollo program. So I asked Jack, have we lost that drive to push into the unknown?

JACK: Oh it’s not lost. I think it’s in our DNA. It started 2 million years ago and it’s continued. Now most of the Earth is been partially explored and now we’ve partially explored the moon. I think that that urge to reach beyond where you are today for sometimes very pragmatic reasons, sometimes very esoteric reasons, is not lost. I don’t think you can get rid of it.

EVA: That’s good to hear.

[“STROLLING ON THE MOON” NASA ARCHIVAL AUDIO]

EVA: Thanks for listening. If you liked what you heard, check out my magazine cover story on the 50th anniversary of the moon landing. This audio story was reported by me, Eva Botkin-Kowacki, and produced by Rebecca Asoulin. Editing by Samantha Laine Perfas, Noelle Swan, and Yvonne Zipp. Sound design by Noel Flatt. Thanks to sound engineer Tim Malone. Special thanks to Timmy Broderick, Em Okrepkie, Dave Scott, Brian Zipp, Nate Zipp, Jimmy Joe Mahon, and Zachary Youngblood. All archival audio is from NASA.

This story is from The Christian Science Monitor, copyright 2019.