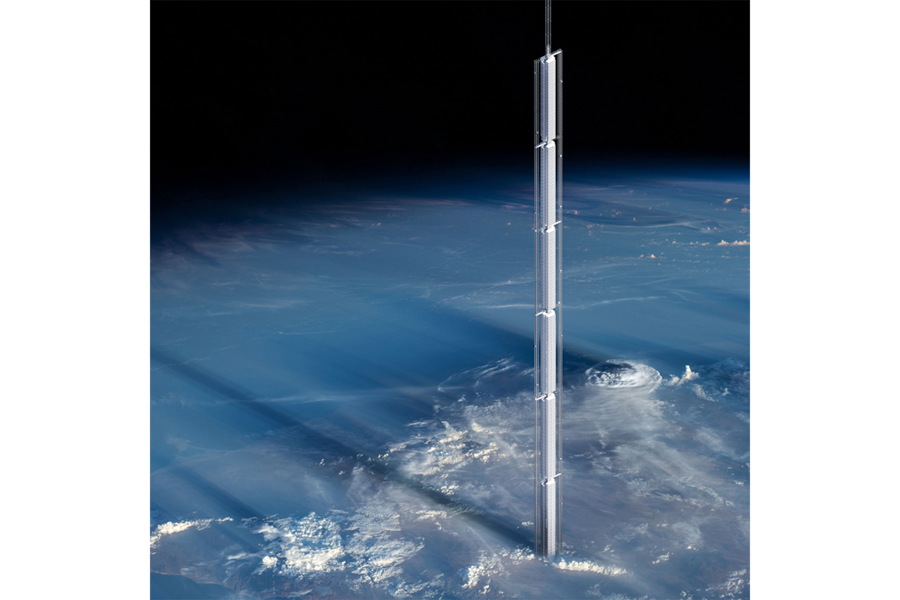

A 20-mile long 'spacescraper' dangling from an asteroid: Could it work?

Loading...

It’s a new approach to an old idea. While Jonathan Swift’s fantastical island city of Laputa stayed aloft via magnets, a New York City design firm envisions using an orbiting asteroid to hang a skyscraper above the Earth.

Clouds Architecture Office espouses a dream-big-or-go-home philosophy with its plan to construct the world’s "tallest building ever." The 20-mile high (or long) megastructure would dangle from an asteroid suspended by a cable system tens of thousands of miles long.

A number of engineering hurdles stand in the way, so would-be atmospheric settlers of tomorrow will have plenty of time to save up for a down payment. Nevertheless, today's humble surface-dwellers may see inspirational value in proposing such castles in the sky, regardless of their feasibility.

Clouds AO’s “Analemma Tower” riffs on the concept of the space elevator, an orbiting counterweight tethered to Earth by an unimaginably long cable that, once built, could provide more affordable access to space.

But rather than a fixed line to the ground, the firm proposes an apartment building hanging off the lower end of a very, very, very long cable attached to an asteroid. The entire system would orbit at the same speed the Earth turns, so it could hover over a relatively narrow area, rather than zipping around many times per day, like the International Space Station does.

The plan calls for an asteroid to be captured and brought back to orbit Earth, similar to NASA’s soon-to-be-cancelled Asteroid Redirect Mission. The space rock would orbit about 30,000 miles above the Earth's surface, and tens of thousands of miles of cable would suspend the low-flying apartment complex, which would span the last 20 miles and nearly scrape the Earth's surface.

The scale of the project is mind-boggling. The building alone would be 60 times as tall as New York’s One World Trade Center, a height that would take Dubai’s Burj Khalifa elevator nearly an hour to climb (although the proposal suggests cableless magnetic elevators). If the entire asteroid-to-bottom-floor span were shrunk to the size of the Eiffel Tower, by comparison the real Eiffel Tower would stand a mere seven hundredths of an inch tall.

Inhabitants could live more than 100,000 feet in the air, where they would enjoy 45 extra minutes of daylight, but it would come at the cost of near-vacuum conditions outside and temperatures comparable to an Antarctic winter, necessitating the recycling of air and water much like a space station.

But a free-flying design affords a number of advantages. By tweaking the elongation of the orbit, builders could specify the figure-eight shaped path the building traces over the Earth. All geosynchronous satellites follow this pattern, from which the structure gets its name: analemma. And the view would be spectacular.

The analemma movement makes the building mobile, with ports of call in New York City and on the western coast of South America where it could dock for loading, unloading, and re-supplying. It would complete one analemma each day.

The design also suggests taking advantage of the skyscraper’s mobility to defray the astronomical building costs, pointing out that Dubai has proven itself a master of low cost, high rise construction. After completion, builders could transport the entire structure to its final New York City-focused orbit.

Rent would cover the remainder of the costs, the architects expect. “It taps into the desire for extreme height, seclusion, and constant mobility. If the recent boom in residential towers proves that sales price per square foot rises with floor elevation, then Analemma Tower will command record prices, justifying its high cost of construction,” the firm wrote.

Recent record-setting apartment prices include a $100 million unit in New York City and a $335 million penthouse in Monaco. Even more astronomical fees for spacescraper real estate would make Analemma Tower accessible only to the hyper-rich.

But Clouds AO won’t be taking deposits anytime soon, because the project faces the challenges of a space elevator, and then some.

“It's basically a space elevator with the lower end free. I think that's actually harder. Probably not 10 times harder though, maybe 1.5 times harder,” suggests Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

The number one problem is the cable. The sheer length and tension require tremendous strength, and theorists can’t come up with a material that could bear more than two-thirds of the load required for a practical elevator, even just on paper.

Another hurdle is space trash from defunct satellites. “The fact that space tethers are often cut in two by a space debris hit is the reason they haven't seen extensive use since the 1990s,” Dr. McDowell tells The Christian Science Monitor in an email. On top of the space elevator style tether, Analemma Tower also presents a large pressurized structure with big windows as a large target for lower flying objects such as birds and planes.

McDowell suspects smaller, higher systems may be feasible (“start small, a hut!”), but he worries about the dangers of dipping too far into the Earth’s thick and breezy atmosphere: “The problems get worse once you start to lower the bottom end into the atmosphere and you have the interaction of the tether with the atmosphere, winds, etc. Then I think it actually gets simpler when you anchor it on the ground.” The jet stream, for example, could buffet the tower at speeds exceeding 100 miles per hour.

And if anything went wrong, a crash could impact more than just the sky dwellers. In the event of a tether snap near the asteroid, the loosed cable could whip around the Earth, wrapping itself over the entire globe 1.2 times. The impact and collapse of a 20-mile building wouldn’t be good news either.

Despite its risk and impracticality, McDowell sees some value in at least discussing the proposal. “It is a fun idea that gets engineers and architects thinking outside the box, which is its purpose,” he says. “For an actual implementation, I think it's a bad idea.”

It’s a sentiment famed science fiction author Neal Stephenson would agree with. Lamenting a shift in innovation from large works of engineering to app and web development, he sees science fiction and big thinking like the Analemma Tower as playing an important role in inspiring engineers and project planners.

“I worry that our inability to match the achievements of the 1960s space program might be symptomatic of a general failure of our society to get big things done. My parents and grandparents witnessed the creation of the airplane, the automobile, nuclear energy, and the computer to name only a few,” he wrote in his essay Innovation Starvation.

Aiming to lead by example, Mr. Stephenson partnered with Arizona State University structural engineer Keith Hjelmstad in 2012 to design a 12-mile-high steel tower that could aid in refueling aircraft and launching spacecraft. He believes such initiatives to be fundamental to the continued success of the human race.

“The imperative to develop new technologies and implement them on a heroic scale no longer seems like the childish preoccupation of a few nerds with slide rules. It’s the only way for the human race to escape from its current predicaments. Too bad we’ve forgotten how to do it,” he wrote.

Advancements in technology have long spurred even more fanciful leaps of inspiration, as the Eiffel Tower reportedly inspired rocketry pioneer Konstantin Tsiolkovsky to outline a proto-space elevator in 1895. We may still lack the technology to build the marvel he imagined, but humans have since found their way to the sky in ways he may not have foreseen.

Space elevators and "spacescrapers" firmly inhabit the realm of impossibility today, but the Burj Khalifa, with its 2,722-foot pinnacle of stone, glass, and computer chip-controlled elevators, would have been far beyond even the imagination of a Stone Age person familiar with only stone hatchets and wooden huts.

As for what will be achievable in the coming centuries, McDowell is bearish, but doesn’t rule out the possibility of an Analemma Tower entirely.

“I would bet against it for at least the next 200 years,” he says.