Study: 6-year old girls say they are less 'brilliant' than boys. Why?

Loading...

Gender stereotypes can be pervasive from the day a child is born. Girls are often dressed in pink, while boys wear blue. Girls are given dolls, and boys get trucks and LEGOs. Girls have princess-themed rooms, but boys get jungles.

Socialized gender norms can be even less explicit, perhaps coming from the language parents, siblings, teachers, and others use to interact with a young child. One of those stereotypes is that boys are smarter than girls.

That idea can have an influence on the kids themselves quite early, according to new research. A study published Thursday in the journal Science found that girls as young as 6 years old have already learned the stereotype that boys are more "brilliant."

And not only have they adopted these stereotypes into their own thinking, the researchers report: they're also acting on them.

"It's heartbreaking to see this association immediately begins to influence the scope of activities that boys and girls are interested in," study lead author Lin Bian, a psychology PhD student at the University of Illinois, says in a phone interview with The Christian Science Monitor.

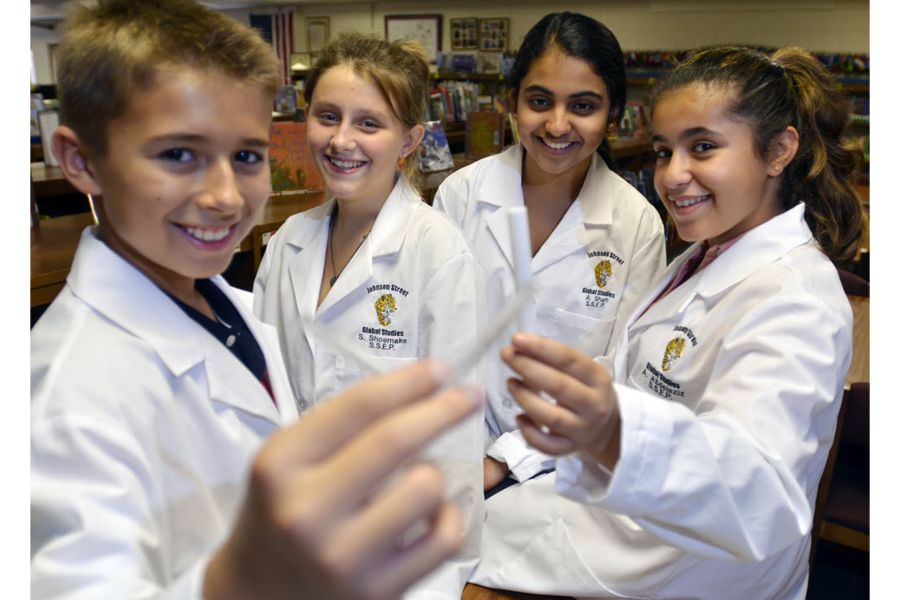

Ms. Bian and her colleagues say their findings point to some of the roots of gender gaps that show up in adulthood, as children might be associating high intelligence with aptitude for careers in many male-dominated fields, like science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). Understanding what is behind children's adoption of such gender stereotypes could help parents and teachers better prepare all kids to make better career choices later in life.

Today, men hold three-quarters of all STEM jobs in the US, while women dominate in fields with lower pay and less prestige. For example, 76 percent of public school teachers in the 2011 to 2012 academic year were women.

With fewer explicit hurdles for women than in previous eras, these career choices may largely be just that – choices. But "I think there is perhaps a danger of talking about those choices as if they just occur in a vacuum," Amanda Diekman, a social psychologist at Miami University in Ohio who was not involved in the study, says in a phone interview with the Monitor.

Students tend to gravitate toward what they enjoy, and what they think they're good at, she says. By the time people are old enough to start making career-oriented decisions, many experiences and interactions have shaped their interests and what they consider their best skills.

A study previously conducted by Bian's co-authors, Sarah-Jane Leslie and Andrei Cimpian, found that STEM researchers across 30 disciplines considered brilliance (defined as an innate, fixed gift or talent) as necessary and more important than hard work to succeed in their field. They also reported, "we found that beliefs about the importance of brilliance to success in a field may predict its female representation."

Bian and her colleagues wanted to know just where that internalized stereotype originated, so they turned to the source: children.

Probing beginnings of the "brilliance = males" stereotype

First, Bian and her colleagues wanted to assess what the children's beliefs were regarding which gender is "really, really smart," which, Bian says, is just a child-friendly way of saying brilliant.

To do that, the researchers told children ages five, six, and seven a story. The child was told that the main character was "really, really smart" but there was no indication as to the gender of the protagonist. Then, the researchers showed the child four pictures of adults, two men and two women, and asked which was the protagonist.

The five-year-olds largely guessed one of the people that was the same gender as them was the "really, really smart" character. But while the male six- and seven-year-olds guessed the brilliant protagonist was male, the older girls began pointing to the men more readily.

"We think this may be the beginning of the stereotype," Bian says.

The researchers still wanted to know if holding this "brilliance = males" belief changed the older children's behavior. This time they described two different games to children, one described as for "children who are really, really smart" and the other for "children who try really, really hard."

When the researchers asked the children questions about which game interested them, they found that the six- and seven-year-old girls were less interested in the game for brilliant children than the boys, but they were equally interested in the game for hard-working children.

"This was our kid-friendly way of talking about a job or careers that require brilliance," Bian explains. So this suggests that as soon as children begin to hold the brilliance gender stereotype, it begins affecting their choices.

There could be some nuances confounding these results, suggests Adrian Furnham, an applied psychologist at the University College London who was not involved in the study. Research has suggested that girls tend to do better at verbal tasks and boys are better with numbers, he says in a phone interview with the Monitor. As such, the nature of the game described to the children could influence their interest as well.

Still, Dr. Furnham says these results are in line with previous work regarding gendered brilliance stereotypes, although none had traced it so young. "The value of the study lies in the observation that this difference occurs so early," he says.

Furnham says this study is highlighting the idea that strong, gendered modesty norms shape a child's brilliance beliefs. "I think children learn from an early age that boys are taught to be boastful and girls to be humble," he explains. And this could be reinforced by what Furnham has found in his own research, which finds that parents tend to talk about their sons as more intelligent than their daughters. So perhaps the parents are inadvertently passing along their perspectives to their children.

Virginia Valian, a psychologist at Hunter College who was not involved in the study, agrees. "The study is compatible with the literature in that in general males inflate and females deflate (on average) their intellectual abilities," she writes in an email to the Monitor.

What changes at age 6?

"Because this is a cultural phenomenon, we suspect the answers won't be simple," Bian says. There are probably many factors influencing a young child's endorsement of the gendered brilliance stereotype, and she and her colleagues intend to identify them through future studies.

But one big thing does change for children between age five and age six, Dr. Diekman points out. That's when most children start going to school.

"It makes sense to me that at the point where we see most kids enter into that system, they start to pick up some different kinds of beliefs, and we see that transition," Diekman says. "Obviously that's speculative, we don't know that it's the system, but I think it makes some sense."

In school, the children are exposed to teachers whose goal is to impart knowledge and shape their students' ways of thinking. They are also exposed to many new people and experiences.

But Bian says it doesn't seem like "children get these ideas about who is brilliant by looking around at who's doing well in school," as her study found that the girls were actually performing better in school.

Hard work versus innate brilliance

Girls' performance in school suggests that perhaps the focus on hard work may be more beneficial. Perhaps the results of this study aren't such bad news for girls, Furnham says. So encouraging girls to take more pride in their intelligence might not be the way to solve this disparity, he says.

Instead, parents and teachers should reinforce the value of hard work for all students. Research conducted by Carol Dweck, a psychologist at Stanford University, found that such a growth mindset focused on hard work can help someone achieve success.

"Part of the problem is the gender problem, but another part of the problem is a general problem of helping students of all ages develop the skills they need to accept challenges and learn from failures," Dr. Valian says.

This can help foster more resilience and love of learning, she says, if someone sees challenges as something to be tackled incrementally rather than with a fixed ability.

Fostering interest in STEM

In addition to helping children see their abilities as something that can be worked at rather than being completely fixed, the stereotype of a scientist and science could be shifted too, Diekman suggests.

"There's this idea that scientists are these crazy smart people who kind of exist on a different plane, that they're kind of qualitatively different from the rest of us," she explains. Similarly, scientific fields are often thought to require some sort of innate brilliance. So "you need to be one of those brilliant people, those brilliant guys, in order to do this brilliant, demanding work."

But, Diekman says, "both of those stereotypes are untrue, at least to some extent." So reframing science and scientists could help all children see scientific goals as something they could work toward and achieve.

Similarly, she adds, "we can start teaching from preschool that science is a mindset in which you are discovering knowledge" and that it's a process, particularly one that includes both success and failure.

Furthermore, Diekman says, science can be framed as more fun earlier on in school. "We often think of science as something we have to do and we have to do it for the good of the economy," she says. "Those things are true, but I think it misses the pure fun and passion and curiosity. Those pieces of it are part of what makes scientists opt in and stay in. And I think if kids early on are thinking, that's for the brilliant kids and I'm not one of those kids, then they select out of that path" before getting to the more exciting opportunities.