Cassini draws near to Saturn – and the end of its own life

Loading...

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft is preparing to zero in on Saturn’s rings starting on Wednesday, as it commences the final stages of its mission to Saturn.

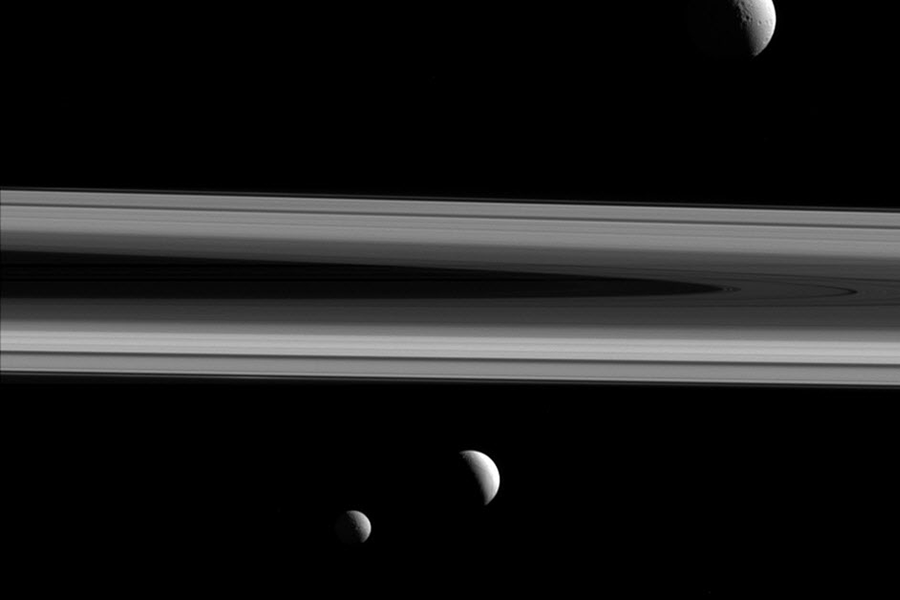

Cassini has taught NASA scientists a great deal about Saturn and its neighborhood, including nearby moons and other celestial bodies. Now, researchers hope to learn more about Saturn’s otherworldly rings.

"We're calling this phase of the mission Cassini's Ring-Grazing Orbits, because we'll be skimming past the outer edge of the rings," said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in a statement. "In addition, we have two instruments that can sample particles and gases as we cross the ringplane, so in a sense Cassini is also 'grazing' on the rings."

Launched in 1997, Cassini has been studying the area since 2004, and although scientists have already learned so much, they say that there is still much further to go. For the next five months, Cassini will circle the planet, diving in and out of its rings once per week, taking samples and learning more about what makes the planet tick.

“It’s still an interesting puzzle,” Dr. Spilker said, according to The Los Angeles Times. “How could this jet stream keep this six-sided shape and rotate as a unit for such a long time? There’s a lot of questions about the rings.”

And Cassini aims to answer these questions in its final months of life, sampling the gasses and dusty particles that compose the rings, including the faint outer rings known as the F and G rings.

The spacecraft will also get a glimpse at the tiny moons that orbit Saturn, close to its rings, including little known Pandora, Atlas, Pan, and Daphnis. Cassini has already visited the better-known moons Enceladus and Titan, and famously discovered liquid methane seas on the latter.

Cassini’s last main engine ignition is scheduled to take place on December 4. After that point, the spacecraft’s smaller thrusters will be used to maneuver the mission in and out of Saturn’s rings.

After twenty years of successful exploration, why is Cassini ending its run now? NASA fans may lament the passing of an age, yet, NASA says, ending the mission now makes sense, as the craft is running out of fuel.

As Nancy Atkinson reported for Universe Today last week:

Of course, the ultimate ‘endgame’ is that Cassini will plunge into Saturn with its “Grand Finale,” ending the mission on September 15, 2017. Since Cassini is running out of fuel, destroying the spacecraft is necessary to ensure “planetary protection,” making sure any potential microbes from Earth that may still be attached to the spacecraft don’t contaminate any of Saturn’s potentially habitable moons.

To prepare for the Grand Finale, Cassini engineers have been slowly adjusting the spacecraft’s orbit since January of this year, doing maneuvers and burns of the engine to bring Cassini into the right orbit so that it can ultimately dive repeatedly through the narrow gap between Saturn and its rings, before making its mission-ending plunge. During some of those final orbits, Cassini will pass as close as 1,012 miles (1,628 kilometers) above the cloudtops of Saturn.

So long, Cassini. You will be missed.