Cosmic jack-o'-lantern: NASA discovers giant 'pumpkin stars'

Loading...

Move over, Charlie Brown: NASA has found its own Great Pumpkin, and it’s quite a bit greater.

Using data from NASA’s Kepler and Swift survey missions, astronomers have discovered a group of fast-spinning, X-ray slinging orange giants. These “pumpkin stars,” so-named for their squashed appearance, may have been created by the merging of two sun-like stars in close binary systems. In other words, two closely orbiting stars appear to reach out and clasp hands like ice skaters in an accelerating spin.

“These 18 stars rotate in just a few days on average, while the sun takes nearly a month,” Steve Howell, lead author and senior scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center, said in a statement. “The rapid rotation amplifies the same kind of activity we see on the sun, such as sunspots and solar flares, and essentially sends it into overdrive.”

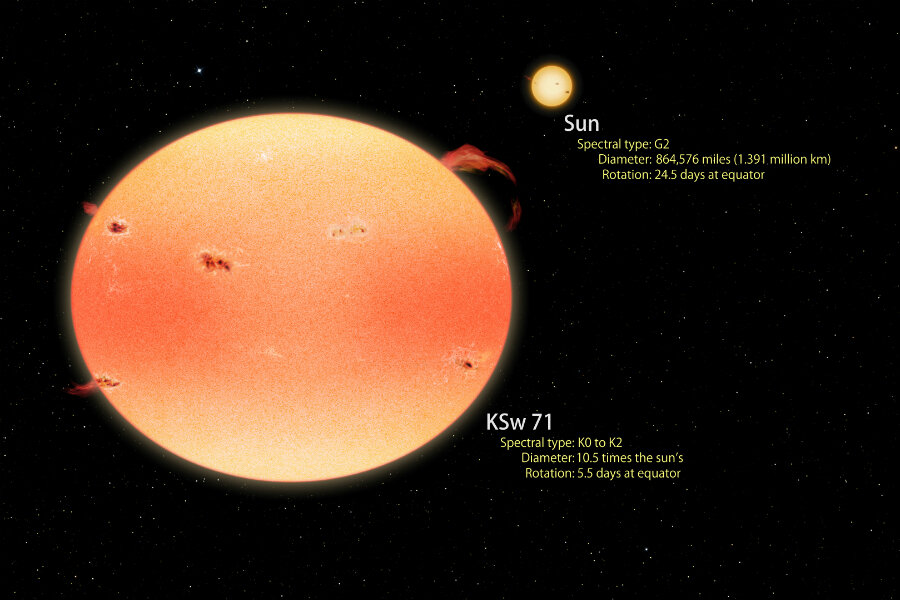

Stars in this particular group produce X-rays at more than 100 times the sun’s peak rate. The “most extreme” member, a K-type orange giant named KSw 71, emits 4,000 times more X-rays than the sun does at its solar maximum. A study detailing this cosmic pumpkin patch was published in the Astrophysical Journal on Monday.

Researchers used Kepler data to determine the sizes and rotation periods of 10 such pumpkin stars. Though relatively similar to our sun in terms of surface temperature, these orange masses were 3 to 10 times larger.

All were giants or subgiants, advanced stages of stellar evolution caused by the depletion of hydrogen fuel. Main-sequence stars, which are generally powered by nuclear fusion, grow large as fused hydrogen atoms build up around the core.

Researchers say their findings may support the work of astronomer Ronald Webbink. In close binary systems, which include two sun-like stars in close proximity, the growth of one star into a giant would theoretically destroy the other.

About four decades ago, Dr. Webbink suggested that these stars would instead merge to form a single, fast-spinning giant. For a while, the new star would be enclosed in an “excretion disk” of expelled gas. That disk would disperse over about 100 million years, revealing an active star.

“Webbink's model suggests we should find about 160 of these stars in the entire Kepler field,” co-author Elena Mason, a researcher at the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics Astronomical Observatory of Trieste, said in a statement. “What we have found is in line with theoretical expectations when we account for the small portion of the field we observed with Swift.”

It’s not the first time our cosmos has shown its Halloween spirit. In 2015, as young goblins went door-to-door in search of candy, an asteroid passed overhead. But it wasn’t just any asteroid – it was a dead comet, and it looked eerily like a skull.

SPACE.com’s Calla Cofield reported:

[The] asteroid 2015 TB145 passed by Earth at a range of just over 300,000 miles (480,000 kilometers), placing it just outside the orbit of the moon, where it posed no threat to the planet. The timing of the flyby earned the asteroid – which is about 2,000 feet (600 meters) across – the nickname “Spooky” and “Great Pumpkin.”