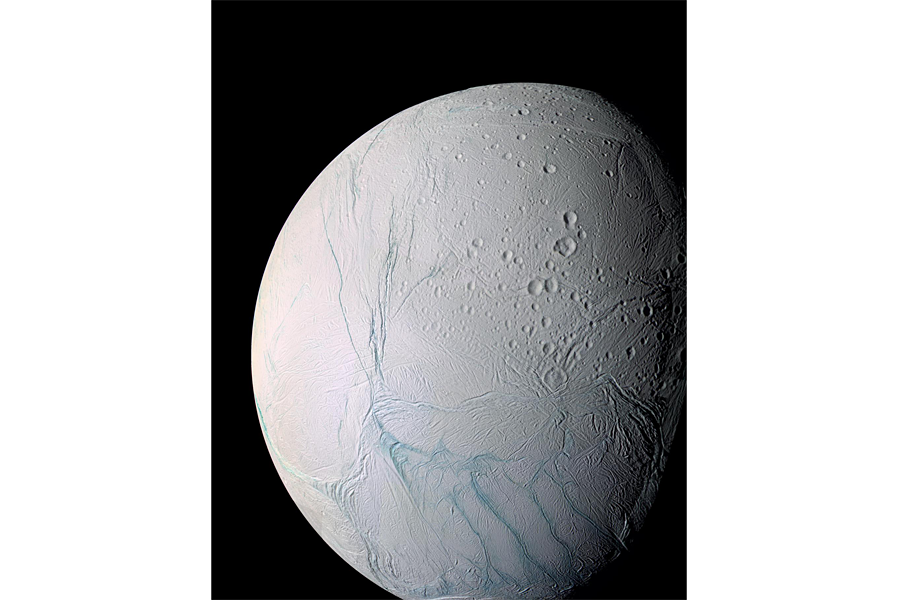

A new model may solve mysteries of Enceladus' icy geysers

Loading...

Icy geysers shooting out of fissures on the south pole of Saturn's icy moon Enceladus have long puzzled scientists. But now, researchers say they may have found a plausible explanation for the prolonged eruptions.

In a new computer model, nearly parallel, vertical slots connect the distinctive "tiger stripe" fissures on the surface of Enceladus to the watery ocean thought to be below. Researchers used a computer model to test this explanation and found it answers a suite of questions swirling around the icy celestial body, as reported in a new paper published in the journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"On Earth, eruptions don't tend to continue for long," study author Edwin Kite, assistant professor of geophysical sciences at the University of Chicago, said in a press release. "When you do see eruptions that continue for a long time, they'll be localized into a few pipelike eruptions with wide spacing between them."

But Enceladus has many fissures that erupt vapor and frost particles continuously.

"It's a puzzle to explain why the fissure system doesn't clog up with its own frost," Dr. Kite said. "And it's a puzzle to explain why the energy removed from the water table by evaporative cooling doesn't just ice things over."

There's also a delay in the eruptions. They reach their peak about five hours after they should based on Enceladus' tides.

The new model, developed by Kite and his colleague Allan Rubin of Princeton University, explains all of those questions and more.

Saturn's gravitational pull is what causes the "tiger stripes" on Enceladus. Those same tidal forces are likely sloshing the ocean deep in the moon. As that water flows in and out of the slots proposed in the new model they generate heat, powering the lagging eruptions.

But "there's a sweet spot," Kite said. Slots that are too wide happen too quickly to explain the five-hour delay. Narrow slots mean the geysers spew too late.

The motion of the water being pumped into these slots heats the water and ice shell, a key that could be observed. Scientists hope to see if the temperatures on the icy surface of Enceladus line up with that explanation in Cassini spacecraft data from flybys.

But real data could also be right here on Earth. Kite and fellow University of Chicago geophysical scientist Douglas MacAyeal are looking to the Ross Ice Shelf in Antarctica for clues. Part of the ice shelf has cracked and is breaking off of the continent.

"In that crack you have strong tidal flow, so it would be interesting to see what a real ice sheet does in an environment that’s analogous in terms of the amplitude of the stresses and the temperatures of the ice," Kite said.