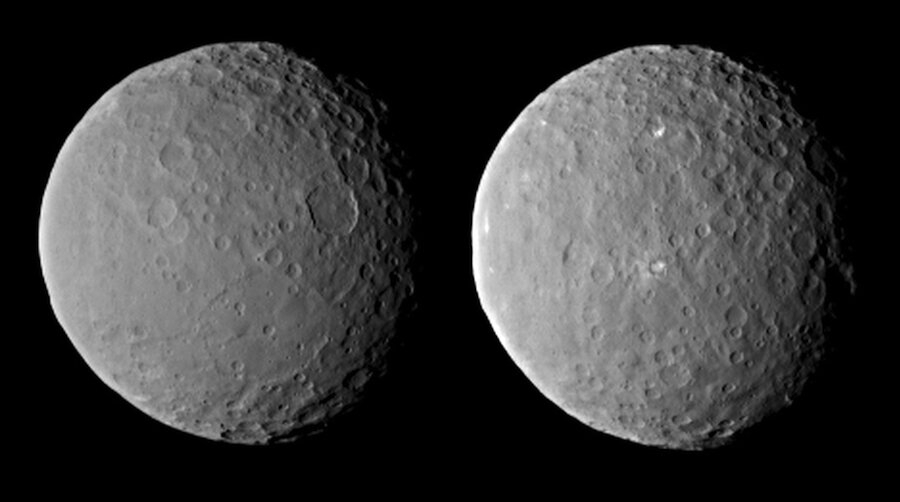

Bright spots on Ceres: Are they moving?

Loading...

Those bright spots on the largest body in the asteroid belt continue to baffle scientists.

Last year, a NASA space probe took high resolution images of Ceres, the only dwarf planet in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. The images revealed a variety of strange, bright spots on the surface of the Texas-sized rock that remain unexplained. Now, a recent study published on the spots adds to the mystery.

A team of scientists studied the reflective areas using precision equipment at the La Silla Observatory in Chile. The equipment was intended to track the motion of the reflective spots caused by Ceres’ rotation, but the team found the motion and movement of the spots was far more complex. The data suggests that the spots may evaporate in sunlight and freeze at night.

"The result was a surprise," said Antonino Lanza, at the INAF-Catania Astrophysical Observatory and co-author of the study, in a press release. "We did find the expected changes to the spectrum from the rotation of Ceres, but with considerable other variations from night to night."

How did the team stumble upon the discovery from 257 million miles away? Precision equipment and the Doppler effect.

"As soon as the Dawn spacecraft revealed the mysterious bright spots on the surface of Ceres, I immediately thought of the possible measurable effects from Earth.” Paolo Molaro, of the INAF-Trieste Astronomical Observatory and lead author of the study, explained in the press release. “As Ceres rotates the spots approach the Earth and then recede again, which affects the spectrum of the reflected sunlight arriving at Earth.”

Dr. Molaro calculated that Ceres spins roughly every nine hours, which means the velocity of the spots spinning away from Earth would be small, but measurable via the Doppler effect and the right equipment.

His team used equipment from the European Southern Observatory site in La Silla, Chile, whose HARPS spectrograph was sensitive enough to measure the shifts in light's frequency. They observed that the spots on Ceres shone brightly and produced a reflective plume when illuminated by the sun. But the plume quickly evaporated. The study notes that "the spots appear bright at dawn on Ceres while they seem to fade by dusk."

The evaporating and dimming of the spots during Ceres' day causes volatility and the unexpected variations.

And while the evaporating and fading could point to the bright spots consisting of water ice, as previous hypothesis suggested, no confirmations have been made on their chemical composition.

"Dawn scientists have not yet established whether the bright spots are made of ice, of evaporated salts, or something else. Thus up to this day the nature of these spots remains a mystery," the study states.

NASA’s Dawn mission launched in 2007 and is tasked with characterizing “the conditions and processes of its earliest history” by studying the largest protoplanets that have remained intact since their creation – Vesta and Ceres, according to NASA. While similar, the two planets followed different evolutionary paths and offer glimpses into the formation of planets in the solar system.

The Dawn spacecraft visited Vesta in 2011-2012. It is currently in orbit around Ceres and continues to collect data on the dwarf planet.