When worlds collide: Earth is really two planets, study finds

Loading...

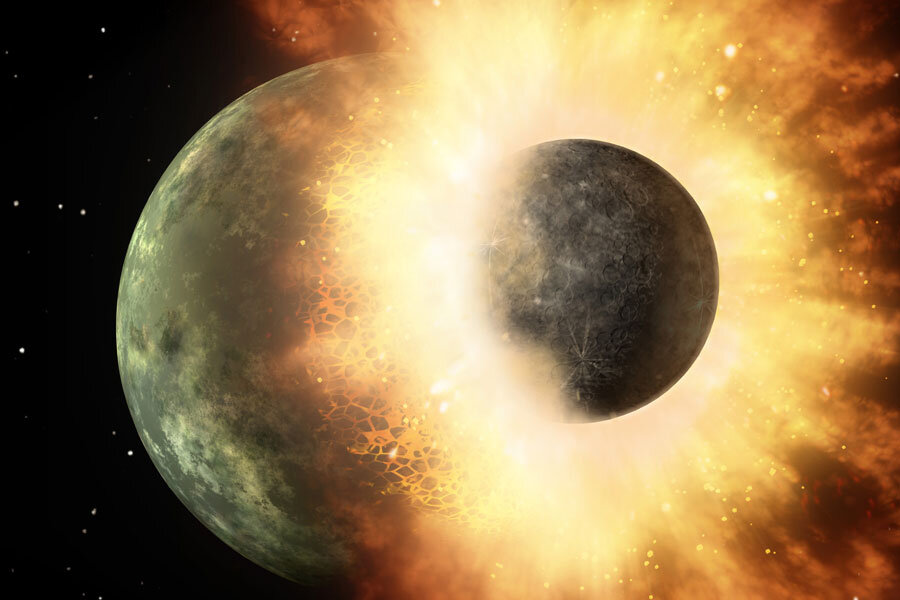

The Earth is actually composed of two planets that fused together during a head-on collision 4.5 billion years ago, suggests a team of scientists in a study published Friday in the journal Science.

Scientists have largely accepted the "giant impact" hypothesis to explain the moon’s existence: about 4.5 billion years ago, a Mars-sized planet named Theia swiped the Earth at a 45-degree angle, throwing up a giant cloud of debris that would form the moon.

But after comparing oxygen isotopes from moon rocks and volcanic rocks from Hawaii and Arizona, these scientists believe Theia’s impact was a “head-on assault,” not a mere sideswipe.

“We don’t see any difference between the Earth’s and the moon’s oxygen isotopes; they’re indistinguishable,” said Edward Young, lead author of the study and a professor of geochemistry and cosmochemistry at the University of California, Los Angeles, in a statement.

And Dr. Young says the isotopes’ similarity proves the scale of the impact Theia had on Earth.

“Had Earth and Theia collided in a glancing side blow, the vast majority of the moon would have been made mainly of Theia, and the Earth and moon should have different oxygen isotopes,” the press release explains. “A head-on collision, however, likely would have resulted in similar chemical composition of both Earth and the moon.”

Because the collision was so forceful, “Theia was thoroughly mixed into both the Earth and the moon, and evenly dispersed between them,” explained Young.

Oxygen, when bonded to silica and other elements, makes up 90 percent of rocks’ volume and 50 percent of their weight, so scientists can use rocks’ oxygen atoms to differentiate between different planetary bodies in our solar system.

Like a chemical “fingerprint,” planets in Earth’s solar system have unique ratios of 17 O and 16 O, two distinct oxygen isotopes.

But because the Earth and moon’s fingerprints are “indistinguishable,” they must both had a fair share of Theia, says Young.

Young and his colleagues are not the first to suggest a head-on collision occurred.

In 2012, Matija Cuk and Sarah Stewart, scientists from the SETI Institute and UC Davis respectively, published a study in Science that supports the same hypothesis.

“It seems unlikely that Theia would be nearly isotopically identical with Earth, so if Theia were a greater contributor to the moon, the moon should differ more substantially from Earth,” Space.com explained in 2012.

Young says each subsequent comparison between rocks further proves Theia’s equal integration into both the moon and Earth.

“As we continue to improve our ability to make measurements, the moon and Earth continue to be more and more alike isotopically,” Young told Space.com.