Five faces, one worm: Scientists uncover genetic oddity

Loading...

Scientists have found worms that can have five different mouths. But not all at once.

An international team of scientists on the island of La Réunion in the Indian Ocean have discovered several new nematode species, each with the ability to take on different physical forms in different environments. Researchers hope their findings will provide new insight into intraspecific evolutionary divergence. The discovery appeared Friday in the journal Science Advances.

“We were very surprised to see five morphs within one species,” says author Ralf Sommer, of the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology.

In their study, researchers identified seven new species, including Pristionchus borbonicus, Pristionchus sycomori, and Pristionchus racemosae. The larvae are carried by pollinator wasps to individual figs. Each fruit is a microecosystem, a tiny fig planet, where Pristionchus can mature and feed.

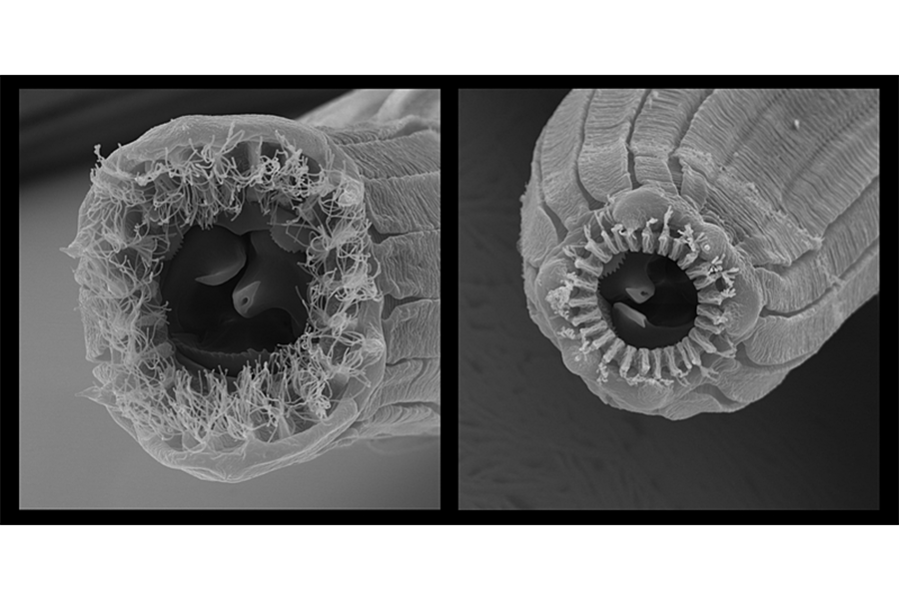

But Dr. Sommer and colleagues noticed something else remarkable about these fig-dwelling worms. Each species had five distinct “morphs,” or physical forms. And each had radically different mouthparts, with “little or no overlap” between morphs. Researchers described some of these structures as “fantastic,” having never seen parallels in other known nematodes.

The observable characteristics of an organism – skin texture, color, hair, and so on – are collectively known as phenotype. These traits correspond to the genotype, the genetic blueprints, of that organism. Often, a gene will code for just one trait. But in other cases, the same genotypes can be used to create radically divergent phenotypes, such as with queen bees and worker bees, whose differences arise not from their genes but from their larval feeding. This phenomenon is known as polyphenism.

Normally, we think of species adapting to its environments through mutation and natural selection. As a species evolves to meet the demands of its environment – like Darwin’s Galapagos finches, which developed different beaks to suit their respective food sources – it can split into separate lineages. Through random mutations over evolutionary time, these lineages become so genetically different that they are considered distinct species.

But these nematodes didn’t get their many mouths through genetic divergence. Through molecular phylogenetic analysis, Sommer and colleagues determined that the worms with all the different mouths were the same species. In each kind of worm, the genotype corresponding to mouth structure was unchanged.

Sommer and colleagues suggest that Pristionchus nematodes can take on different morphological characteristics based on their fig ecosystems.

“Figs are a very interesting but somewhat unusual ecosystem,” Sommer says. “All organisms in the fig fruit arrive their by the fig wasp vector. This ecosystem is therefore highly predictable and shows a succession from early to late stages. We currently believe that in the early fig, Pristionchus nematodes feed on yeast and bacteria. Later, other nematode species develop in the fig and Pristionchus can predate on them when expressing other morphs.”

According to Sommer, these organisms present an exceptional research opportunity for evolutionary biologists.

“This work shows the power of phenotypic plasticity as a mechanism for evolutionary diversification,” Sommer says. “In general, phenotypic plasticity describes the property of organisms to form different phenotypes dependent on the environment. Therefore, plasticity allows [us to] investigate how genetic and environmental factors interact to generate phenotypes.”